What can be harder to talk about than even religion and politics?

Health.

At least when it comes to religion and politics, we’re all well aware of serious disagreements at hand.

But in many matters of health, at least the public perception is that most people—especially most smart people—agree on the best way to care for the sick, prevent disease, and promote health generally.

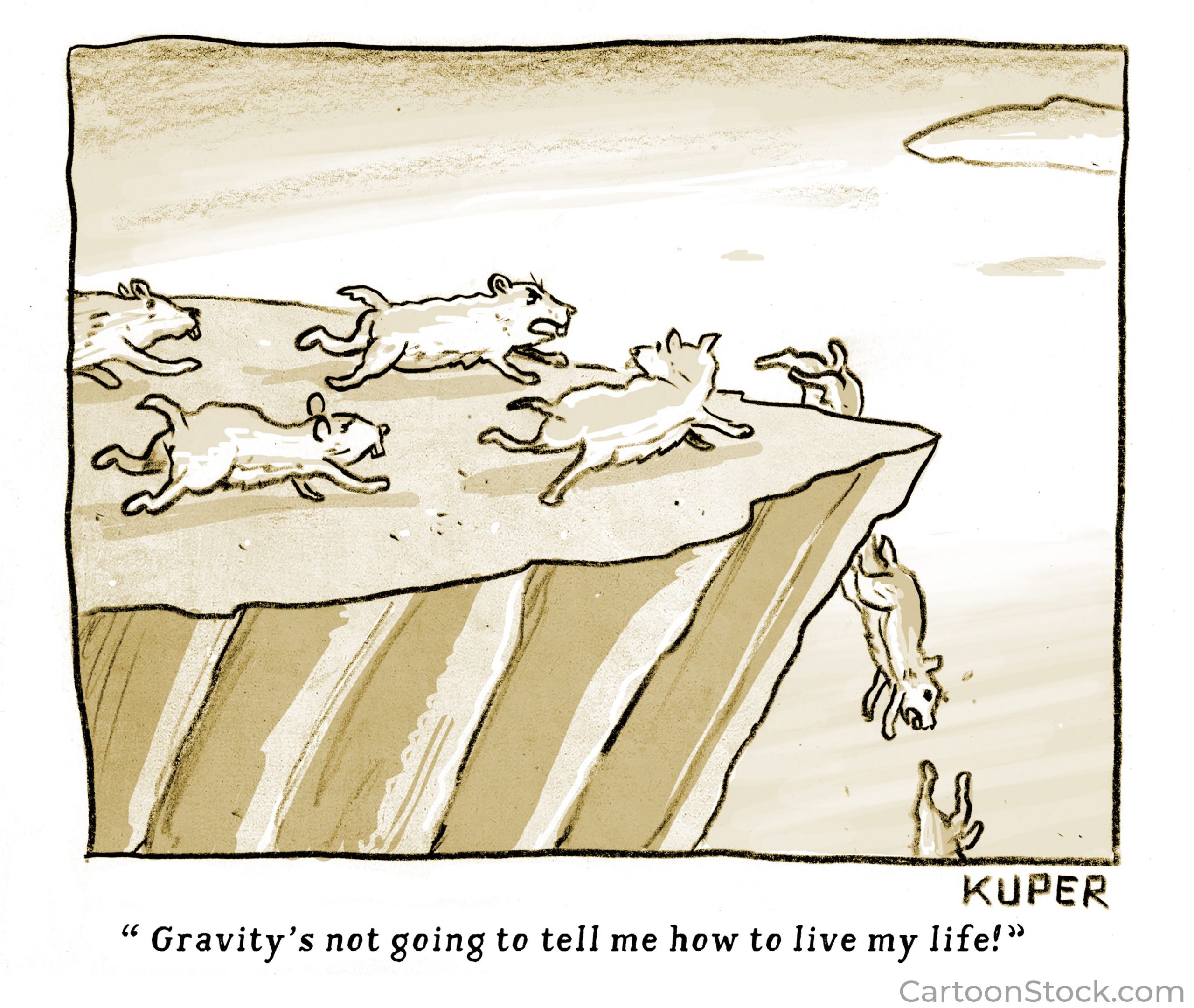

From this vantage point, “science” is agreed on most of the fundamentals and it’s really only the loonies that disagree when it comes to established medical treatments and public health policy.

In one sense, that’s not all that different from conversation around other hot topics, especially climate change and sexuality. On each of those issues, perceptions of consensus are likewise accompanied by portrayals of those who disagree as fundamentally dangerous. The various labels applied to those questioning the dominant paradigm around LGBT rights is well-known. Similar pejoratives exist in the climate change conversation, with the term “climate change denier” first coined by George Marshall and co-author Mark Lynas in a 2003 op-ed in the New Statesman. As Ralph Benko points out, the term was intended to “sting”—hearkening as it does to “holocaust denial” and casting those who question as willfully denying a patently obvious reality (aka, clearly “crazies”).

Similar pejorative terms have been used for those raising questions about the prevailing opinion on coronavirus these weeks.

What is it that makes these conversations especially hard?

Perhaps it’s both the perceived and real threat on existence itself. Compared with disagreements around tax policy or God’s existence (however consequential these issues are in other realms), the issues above are experienced as having a clear bearing on visceral, real-and-present dangers to the well-being of individual happiness, public health and even the health of the entire planet.

If it’s a bad sign generally speaking to be unable to openly disagree in any conversation, is it any different for health matters?

So, maybe it’s understandable, then, that they’re a little harder to navigate. On one level, this might invite some added empathy for our conversation partners (and ourselves), when things get a little heated.

Hey, let’s give ourselves a break. These aren’t your normal, garden variety disagreements.

On another level, this might suggest an added level of care for anyone engaging on these particular issues. While disagreement on most any question can trigger a visceral fight or flight reaction (especially these days), perhaps we can appreciate why this specific kind of a question does so quickly.

As Arthur Pena articulated in his recent essay, from a climate believer’s point of view, “the ‘denier’s’ denial reflect[s] a dangerously delusional belief contributing to a climate catastrophe that could conceivably make the planet uninhabitable.” That raises the understandable question, “Why engage with such a person?”

Similar levels of threat could be identified on other issues – from immigration and race issues (e.g., Black Lives Matter) to the ongoing debates around abortion and sexuality.

But health? After thousands of years of human history, you’d think we would have arrived at some kind of consensus about something like…child birth? No way! From the endless debates around birthing to similar grappling over mental health treatment and cancer care, pointed contestation over the best way to support those facing health issues continues. There may be no more difficult conversation to navigate, however, than infectious disease control and vaccination itself.

To even raise questions on the topic has often been experienced as an inherent threat to public health. That’s why while the Village Square’s past work to facilitate conversation has included a wide range of issues—from immigration and policing to climate change, religion, and sexuality, they have typically stayed far away from health matters.

If it’s a bad sign generally speaking to be unable to openly disagree in a conversation, is it any different for health matters?

Some would argue that yes—it’s best if some disagreements remain less discussed, so as to not harm public health (vaccinations dialogue prompting more openness to critiques, for example). But in the internet age, proponents of suppressed ideas can become their own publishers. And the more their own genuine question get framed as mere “fanaticism” or “conspiracy,” the more the disconnect and contempt grows.

Is that healthy and good in the long-term?

Only in a dystopian novel. However much we may disagree on some health matters ourselves, we think it best if we could at least talk about these matters more—and more openly and transparently.

Even if it’s hard.

Whatever side effects there may be from such a conversation, the chance to know more of the full truth is surely worth it.

And when it turns out to still be especially hard, let’s not be surprised. We might even give ourselves a little break too.

These are life and death matters we’re talking about, after all. Since when was that supposed to be easy?