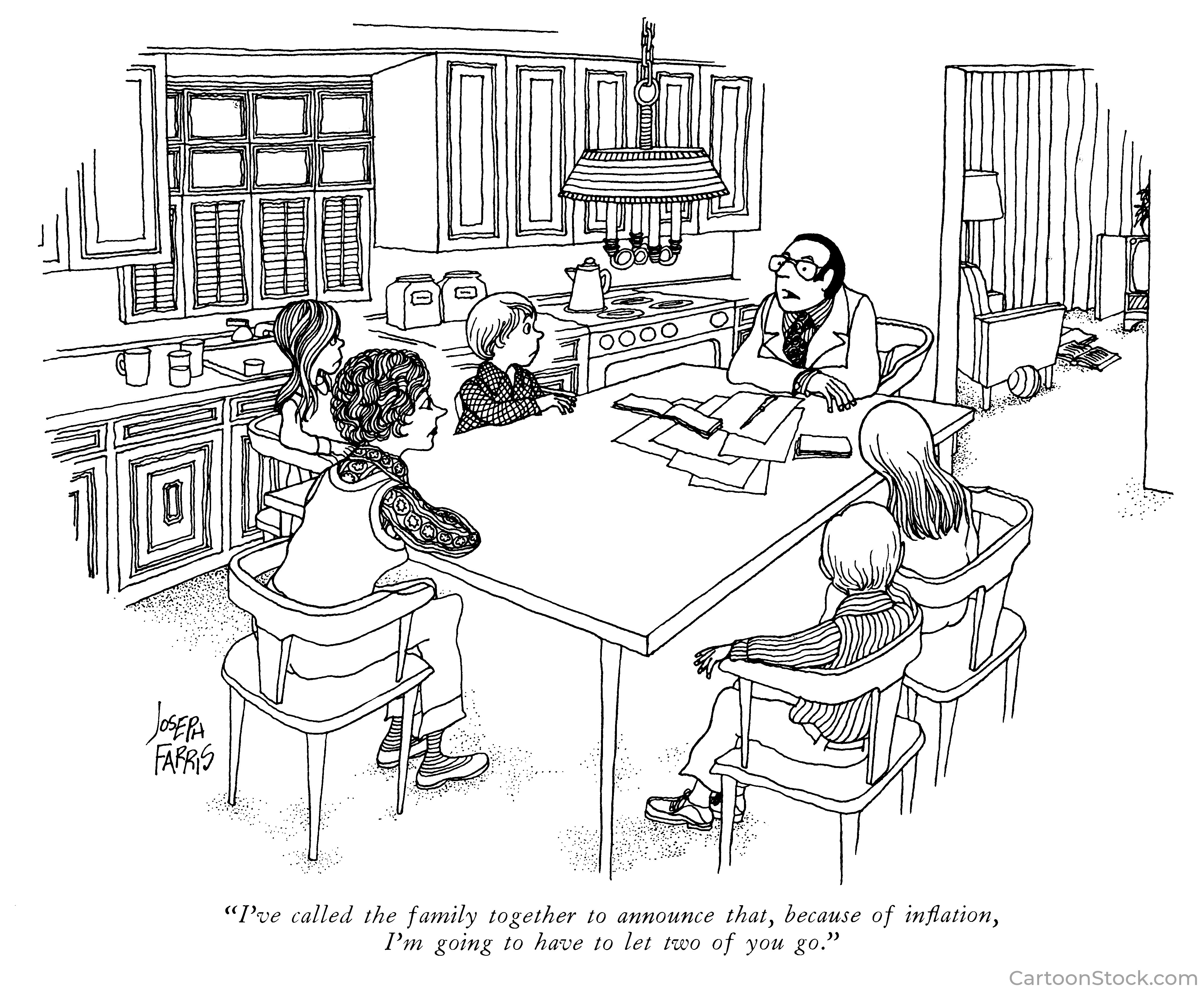

In the classic 1984 movie The Karate Kid, Mr. Miyagi teaches the young Daniel LaRusso many valuable lessons. For example, when Daniel expresses a tepid desire to begin karate training, Mr. Miyagi tutors him on the importance of wholehearted commitment:

“Daniel-san, must talk. Walk on road. Walk right side, safe. Walk left side, safe. Walk middle, sooner or later, [makes squish gesture] get squish, just like grape. Here karate, same thing. Either you karate do, yes, or karate-do, no. You karate do, guess so, [makes squish gesture] just like grape.”

In his most recent general conference address, Elder David A. Bednar recalled an analogous lesson that Elder Jeffrey R. Holland taught him in 1998:

We are witnessing an ever greater movement toward polarity. The middle-ground options will be removed from us as Latter-day Saints. The middle of the road will be withdrawn. If you are treading water in the current of a river, you will go somewhere. You simply will go wherever the current takes you. Going with the stream, following the tide, drifting in the current will not do. Choices have to be made. Not making a choice is a choice. Learn to choose now.

Never has the wisdom of a fictional veteran karate master and an apostle of the Lord Jesus Christ been more indispensable. If we would avoid getting squished like a grape, we must choose to walk on one side of the road or the other. If we would avoid getting swept away in a current, we must swim upstream or against the tide.

In his recently published book Live Not By Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents, Rod Dreher issues a similar warning and a wake-up call to contemporary Christians, and by extension, to all people of faith and goodwill. In essence, Dreher argues that we must awaken from our self-satisfied slumber and begin to more fully resist evil because we may soon encounter adversity that makes the squishing of grapes, or the rushing of rapids, seem like a joyride. If Dreher is right—and the insights of authors from Alexis de Tocqueville to George Orwell, Aldous Huxley, and Aleksander Solzhenitsyn suggest that he is not wrong—Americans are gradually succumbing to a dangerous and subtle new form of totalitarianism. (For an excellent introduction to Live Not By Lies, see Yoram Hazony’s recent interview with Rod Dreher.)

Without descending entirely into gloomy, doomsday rhetoric or outright apocalypticism, Dreher contends that halfhearted Christians can hardly hope to weather the gathering secular storm:

A time of painful testing, even persecution, is coming. Lukewarm or shallow Christians will not come through with their faith intact. Christians today must dig deep into the Bible and church tradition and teach themselves how and why today’s post-Christian world, with its self-centeredness, its quest for happiness and rejection of sacred order and transcendent values, is a rival religion to authentic Christianity. We should also see how many of the world’s values have been absorbed into Christian life and practice (emphasis my own).

In The Karate Kid, weak and poorly trained karate students inevitably received thorough beatings at the hands, and the feet, of the Cobra Kai. Can we, without serious and consistent commitment to Jesus Christ and His Gospel, ever expect to emerge victorious against the onslaught of evil that Dreher foresees? In the words of another fictional martial arts sensei, “Forget about it!”

What, then, is the nature of this new, soft totalitarian threat that so troubles Dreher?

“Elites and elite institutions,” Dreher writes:

Are abandoning old-fashioned liberalism, based in defending the rights of the individual, and replacing it with a progressive creed that regards justice in terms of groups. It encourages people to identify with groups—ethnic, sexual, and otherwise—and to think of Good and Evil as a matter of power dynamics among the groups. A utopian vision drives these progressives, one that compels them to seek to rewrite history and reinvent language to reflect their ideals of social justice.

Their worldview in principle has no place for forgiveness, repentance, and civic reconciliation.

Dreher alerts his readers to the way that this new, soft totalitarianism currently operates: “Under the guise of ‘diversity,’ ‘inclusivity,’ ‘equity,’ and other egalitarian jargon, the Left creates powerful mechanisms for controlling thought and discourse and marginalizes dissenters as evil.” Lest anyone suppose that he exaggerates, just read Dreher’s recent posts (here and here) at The American Conservative. In his excellent review of Live Not By Lies, Daniel J. Mahoney adds a second witness:

The demands of the Woke have become increasingly coercive, including the curtailment of the speech—and even employment—of those who question their reckless social and cultural agenda. Dreher speaks freely of an increasingly ascendant ‘soft totalitarianism.’ In the present circumstances, such an appellation does not strike this reader as particularly hyperbolic. Like the totalitarians of old, the new totalitarians wish to erase historical memory and to rewrite history according to the willful ideological demands of the moment. They are cruel, vindictive, and moralistic, and thus incapable of acknowledging human frailty and fallibility. Their worldview in principle has no place for forgiveness, repentance, and civic reconciliation. Politics for them is war by other means—and perhaps not just other means.

Dreher admits that, along with most Americans, he believed “that the menace of totalitarianism had passed.” His own wake-up call came in the form of warnings from men and women who had survived communist oppression, people who considered that Americans are “hopelessly naive on the subject.” These courageous survivors of past totalitarianism uniformly denounced what Dreher calls the “pre-totalitarian” conditions of the present-day United States. Though conditions under totalitarianism, old or new, are bleak, these survivors demonstrate that the triumph of evil is not inevitable. Like proven karate masters, Dreher’s newfound Eastern European friends instructed him on the importance of wholehearted commitment to faith, family, and freedom, even in the face of relentless opposition. These friends, like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, taught Dreher, and they also can teach us, to “live not by lies.”

How do we live not by lies?

In Dreher’s estimation, in addition to discerning and understanding the nature of this new, soft totalitarianism, we must put our spiritual lives in order and begin to mount a resistance. In the first part of Live Not By Lies, Dreher explores the sources of totalitarianism and reveals the “troubling parallels between contemporary society and the ones that gave birth to twentieth-century totalitarianism.” He places particular emphasis on the ways in which the rising soft totalitarianism has infiltrated and dominated most major institutions, including academia, government, corporations, the media, surveillance technology, religion, and even the everyday lives of common people. In the second part of his book, Dreher “examines in greater detail forms, methods, and sources of resistance to soft totalitarianism’s lies.” In short, Dreher’s formula for living in truth is first to recognize the lies inherent in emerging totalitarian ideologies, and then to energetically resist them. To quote Dreher’s Slovakian friend, Father Kolaković, in order to successfully live within the truth we must “See. Judge. Act.”

In his review, Mahoney adds his own counsel:

Dreher’s perspective, which leans toward the apocalyptic, must be supplemented by tough-minded thinking and prudent action. I do not believe Dreher’s perspective is unduly alarmist, but I do believe it needs to be leavened by a sense that civic deliberation and action can help us resist the totalitarian tide. Alarm should give rise to spirited thought and action in the service of the common good.

Returning to The Karate Kid, I would add we also need more courageous Mr. Miyagis who are prepared to train committed young Daniel LaRussos in the spiritual and intellectual martial arts. Metaphorically speaking, only the Daniel-san’s who have sanded the floor, waxed the car, and painted the fence and the house will be prepared to resist and defeat the Cobra Kai of the advancing totalitarian threat. The Rex-Kwon-Do training that is characteristic of too many modern institutions simply will not suffice.

Unlike many popular authors who feign neutrality or claim to convey cultural criticism from a lofty, apolitical perch, Dreher has chosen to walk on the right side of the road. He has chosen to swim upstream and against the current. In his book Live Not By Lies, Dreher delivers a veritable crane kick to the face of the new, soft totalitarianism. Whether or not his analysis is accurate and his recipe for resistance is robust is for the reader to determine. But there is no mistaking where Dreher stands: he is a committed Christian with a strong desire to stand up for truth because it is the right thing to do. He draws strength from his faith in Christ and from faithful friends who fear God more than men.

Some might wonder if Dreher has simply allowed his conservative Christian imagination to run wild. Things can’t be that bad, can they? Totalitarianism is a thing of the past that can never happen to us here, can it? Dreher responds frankly:

Of course, it can. The technological capability to implement such a system of discipline and control in the West already exists. The only barriers preventing it from being imposed are political resistance by unwilling majorities and constitutional resistance by the judiciary.

If Dreher were a lone voice crying in the wilderness, it might seem easy to ignore or dismiss his warnings as the ravings of a disgruntled religious conservative. However, Dreher’s new book Live Not By Lies represents only one melody in a growing chorus of voices that have warned against this new totalitarianism. As mentioned earlier, the foundation for understanding the threat of soft totalitarianism was laid by authors from Alexis de Tocqueville to George Orwell, Aldous Huxley, and Aleksander Solzhenitsyn. To these, Dreher adds the voices of many others, most notably Sir Roger Scruton, Heather Mac Donald, Hannah Arendt, Philip Rieff, and a slew of survivors of totalitarianism, including the courageous Benda family.

In the midst of this chorus of powerful conservative voices, Dreher’s own voice is not negligible. He describes the new, soft totalitarianism as “therapeutic” because “it masks its hatred of dissenters from its utopian ideology in the guise of helping and healing.” This is a key point. While posing as a benevolent caretaker, the new totalitarianism seeks total control over thoughts, emotions, ideas, and opinions. The new totalitarianism often behaves more like an overbearing nurse than an oppressive big brother. C.S. Lewis described the same phenomenon as follows:

Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.

Unfortunately, dissenters from the new totalitarianism too often fail to speak up or resist, because they are afraid. Dreher laments that they often find “their businesses, careers, and reputations destroyed.” They are “pushed out of the public square, stigmatized, canceled, and demonized as racists, sexists, homophobes, and the like.” Furthermore, they may waver “because they are confident that no one will join them or defend them.

Another reason why dissenters from the new totalitarianism may vacillate is because they are too comfortable. “Relatively few contemporary Christians are prepared to suffer for the faith,” Dreher argues, “because the therapeutic society that has formed them denies the purpose of suffering in the first place, and the idea of bearing pain for the sake of truth seems ridiculous.” This is another key point. Although Dreher could probably afford to focus more intently on the joy of faith in Christ and the sweetness of His Gospel, he is not wrong about the positive role of suffering in Christian discipleship or life in general. “The deeper that sorrow carves into your being,” wrote the poet Khalil Gibran, “the more joy you can contain.”

Dreher dedicates an entire chapter to what he calls “The Gift of Suffering.” Without seeking suffering, Christian dissidents must comprehend that, as one of Dreher’s new Hungarian friends explained, “suffering is a normal part of life—even part of a good life, in that suffering teaches us how to be patient, kind, and loving.” Dreher’s astute insight (an insight that Daniel J. Mahoney best articulated) is that the new, soft totalitarianism is a counterfeit of Christianity, a Christianity without Christ, or as Aldous Huxley described it in Brave New World, a “Christianity without tears.” “The old totalitarianism,” Dreher explains, “conquered societies through fear of pain; the new one will conquer primarily through manipulating people’s love of pleasure and fear of discomfort.” As Dreher rightly contests, this counterfeit Christianity will not endure:

The faith of martyrs, and confessors like those who survived to bear witness, is a far cry from the therapeutic religion of the middle-class suburbs, the sermonizing of politicized congregations of the Left and the Right, and the health-and-wealth message of ‘prosperity gospel’ churches. These and other feeble forms of the faith will be quickly burned away in the face of the slightest persecution.

In Live Not By Lies, Dreher draws extensively upon the work of Philip Rieff, author of The Triumph of the Therapeutic: Uses of Faith after Freud. Rieff disclosed the ways in which the rise of “Psychological Man” in the place of “Religious Man” has contributed to the disintegration of Western civilization. Dreher notes that “Rieff foresaw the future of religion as devolution into watery spirituality,” or that which sociologists of religion Christian Smith and Melinda Lundquist Denton described as “Moralistic Therapeutic Deism”. In the guise of Christianity, the new, soft totalitarianism promotes this watery spirituality, woke ideology, and identity politics while attempting to crush God-fearing Christians and other people of sincere faith. It infuses hedonism and complacency with religious fervor, and it cloaks hatred and oppression in the language of love.

Dreher also draws extensively upon the work of Hannah Arendt, author of The Origins of Totalitarianism, in order to help readers see totalitarianism coming from afar. Arendt outlined several societal conditions in which totalitarianism thrives, including rampant loneliness and atomization, lost faith in hierarchies and institutions, pervasive desires to transgress and destroy, propaganda, and the willingness to believe useful lies, a mania for ideology, and the prioritization of loyalty over expertise. Dreher is careful to mention that such societal conditions do not make totalitarianism inevitable, but they do reveal that “weaknesses in contemporary American society are consonant with a pre-totalitarian state.”

Throughout the book, Dreher is also careful to distinguish between the old and new forms of totalitarianism. Dreher exposes the complicity of progressivism in the rise of the new totalitarianism. He peels back the layers of modernity to reveal progressive thought as a full-fledged religion, complete with heresy hunters and a cult of social justice. In the religion of progress, Dreher argues, the central fact of human existence is power, and how it is used. This is also the merciless doctrine of the Cobra Kai sensei John Kreese and his vicious pupil Johnny Lawrence.

Preachers of progressivism proclaim that there is no objective truth, that populations are divided between oppressors and the oppressed, and that an obsession with language should take the place of reason and dialogue. With corporations, academia, the media, and other institutions already saturated with progressive dogma, Dreher suggests that surveillance capitalism has injected the same progressive dogma into almost every American home. “Powerful corporate and state actors,” Dreher warns, “will control populations by massaging them with digital velvet gloves, and by convincing them to surrender political liberties for security and convenience.”

What, therefore, is to be done?

Dreher promotes true religion as the bedrock of the resistance against the new totalitarianism.

In the second part of his book, Dreher encourages dissidents from the new totalitarianism to value nothing more than truth, to choose a life apart from the crowd, to reject doublethink and fight for free speech, to cherish truth-telling while exercising prudence, and to follow Father Kolaković’s formula for living within the truth: “See. Judge. Act.” Dreher also emphasizes the importance of cultivating cultural memory and strengthening families as the core resistance cells. In particular, Dreher encourages parents to model moral courage, to teach children to love what is good, true, and beautiful, and to prepare to make sacrifices for the greater good.

Perhaps most importantly, and in contrast to counterfeit Christianity, Dreher promotes true religion as the bedrock of the resistance against the new totalitarianism. The bedrock of faith in Christ is founded upon genuine spiritual practices such as repentance, prayer, immersion in the word of God as contained in scripture, obedience to God, and service to others. Dreher shares some of the spiritual exercises of his friends, many of whom came to know God through intense suffering and prolonged imprisonment. One of these valiant souls, Silvester Krčméry memorized passages from the New Testament and treasured up the words of Christ in his heart while behind bars:

“Indeed,” Krčméry wrote, “as one’s spiritual life intensifies, things become clearer and the essence of God is more easily understood. Sometimes one word, or a single sentence from Scripture, is enough to fill a person with a special light. An insight or new meaning is revealed and penetrates one’s inner being and remains there for weeks or months at a time.”

Krčméry was willing “to endure all for the sake of Christ.”

Dreher also interviewed the famous Christian dissident Alexander Ogorodnikov who remembered the story of a prison guard whose conscience finally compelled him to confess that he had witnessed the execution of a group of priests in Russia. The guard told Ogorodnikov how a KGB agent put the priests in rows and asked each one of them “Is there a God?” or “Does God exist?” When a priest answered in the affirmative, the KGB agent shot him in the head, and calmly moved on to the next priest. Dreher records that “in a voice cracking with emotion, the old prisoner says, ‘Not one of those priests denied Christ.’”

Amplified by the witness of his Christian dissident friends, Dreher raises a searching question: are we true followers, or merely admirers of the Lord Jesus Christ? Dreher suggests that we may distinguish true disciples from admirers of Christ by how we act in response to counterfeit Christianity and the new, soft totalitarianism. A true disciple of Jesus Christ is willing to pay the cost and appreciate the blessings of discipleship. He strives to love his enemies, to do good to those who hate him, to pray for those who despitefully use him, and to bless those who persecute him. He moves steadily, as Elder Neal A. Maxwell taught, “in the posture of repentance” from “a mere acknowledgment of Jesus on to admiration of Jesus, then on to adoration of Jesus, and finally to emulation of Jesus.”

We may never be thrown into prison or shot like victims of the old totalitarianism. We might not even lose our reputations or standing in society in the fashion of the pre-totalitarian society in which we now live. But if Dreher is right, sooner or later, each one of us will have the opportunity to demonstrate where our true allegiance lies. In the meantime, when the new, soft totalitarianism threatens to sweep the leg, we can be ready with the crane kick. We can embrace the wisdom of Mr. Miyagi by choosing to walk solidly on one side of the road or the other. We can hearken to the counsel of Elder Holland by choosing to swim upstream or against the current. And we can take courage from Christian dissidents, both past and present, who demonstrate the power of choosing to live not by lies.