Few books make for better Holy Week reading than The Pilgrim’s Progress.

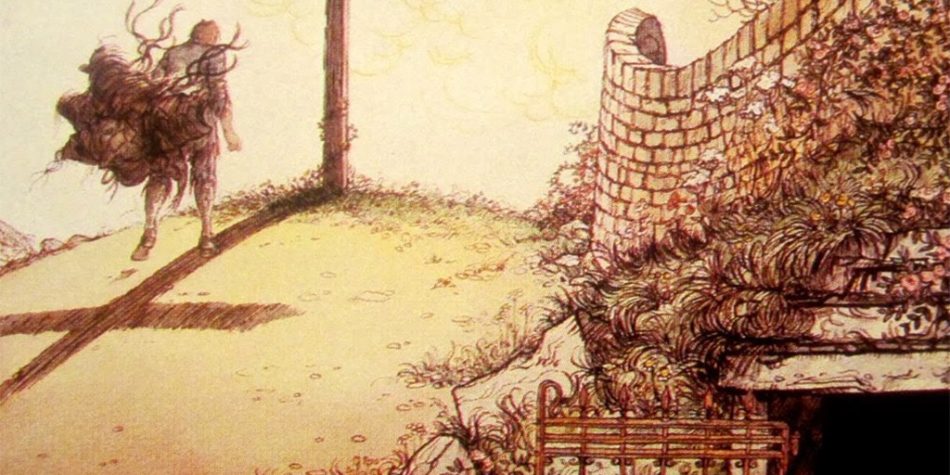

One of the most moving scenes of John Bunyan’s classic 17th-century work is when the hero named Christian discovers a saving grace early in his journey to the Celestial City. Christian, carrying a burdensome load (symbolic of his sin-wounded soul), beholds a cross and approaches it. As he does so, “his burden loosed from off his Shoulders, and fell from off his back; and began to tumble; and so continued to do, till it came to the mouth of the Sepulcher, where it fell in, and I saw it no more.”

This delights Christian. “He hath given me rest, by his sorrow; and life, by his death,” he says, in obvious allusion to the Christ.

Our hero continues to stand there, enchanted by such an unexpected deliverance. “It was very surprising to him,” the narrator tells us, “that the sight of the Cross should thus ease him of his burden. He looked therefore, and looked again, even till the springs that were in his head sent the waters down his cheeks.”

He then sings,

Thus far did I come loaden with my sin,

Nor could ought ease the grief that I was in,

Till I came hither: What a place is this?

Must here be the beginning of my bliss?

Must here the burden fall from off my back?

Must here the strings that bound it to me, crack?

Blest Cross! blest Sepulcher! blest rather be

The Man that there was put to shame for me.

Growing up as a Latter-day Saint in Utah, the cross never held this kind of spell on me. I rarely saw one. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints does not use the cross as an official symbol. You will not find one either inside or atop any of our houses of worship or on any of our books of scripture and song. You may occasionally encounter an artistic depiction of Calvary (the Greek name for the place outside ancient Jerusalem where the Christ was crucified), but even that is rare. Utah is by and large the land of the cross-less chapel and golden-angel-attired temple. The sweetness of the cross continues to seep steadily into my soul.

Even so, Bunyan’s allegory should appeal to any Latter-day Saint because it helps us better connect with fellow Christians. He merges our preferred symbol of hope—the empty tomb—with the symbol of Protestant Christians—the empty cross. As Christianity Today editor-in-chief Daniel Harrell recently wrote, “Protestants note how our crosses hang vacant to signify God’s finished work and final victory” (italics added). The empty tomb and the empty cross can symbolize the same thing. And there is nothing amiss, in my view, with the Catholic crucifix that, instead of being empty, features the body of the Christ nailed to the cross. Seeing the vulnerable and suffering Savior can be a potent reminder that, as official Catholic teaching says, “the way of perfection passes by way of the Cross. There is no holiness without renunciation and spiritual battle” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, Second Edition, 2019).

As I age and experience more of the Christian world through what I read and encounter, the sweetness of the cross continues to seep steadily into my soul. Five years ago, I was moved by what I saw one summer evening in Layton, Utah. My wife and I discovered a park near our home. The area was well-obscured by tall trees, bushy and thick with green foliage. While our daughters enjoyed the jungle gym, I explored the other surroundings. A few minutes later, I saw it—standing taller than the trees was the unexpected beauty of a cross, silhouetted by a golden ball of fire that was the setting sun. This cross, I learned, stands atop St. Rose of Lima Catholic Church, a hidden gem in Utah’s Davis County. This image is etched in my mind as a symbol of the Father of lights—the common Father of all humanity—who surrounds our personal dark crosses with His eternal light.

Christians understand that life—especially a life of faith—has difficulty written into the terms of service. “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me,” Jesus said. Even those who are not Christian, as they describe their burdens, speak of having a “cross to bear.” For both groups, some of these challenges are ponderous—debilitating disease, single parenthood, unemployment, death of a loved one, to name just a few. Others are silly. The LEGO movie I recently watched with my daughters comes to mind. Batman laments that he is “way too buff!” to fit into a tight space within Superman’s fortress of solitude. “You also have beautiful abs, sir,” his computer tells him. “That’s my cross to bear!” Batman responds.

Though we live in what some call a “secular age,” the traces of Calvary are everywhere.

If you know something of Jesus’s suffering, it probably makes you uncomfortable. He lost copious amounts of blood in the garden of Gethsemane; His friends abandoned Him; a crown of thorns dug into His scalp; a whip made a mess of His back; spittle and taunts flew into His face; nails pierced His hands and feet. This gruesome scene culminated on the cross.

Interesting, isn’t it? These events are what we remember on the day of Holy Week known as Good Friday. On its surface, everything about Good Friday seems “bad.” Jesus’s despair bottoms out. He feels abandoned by His Heavenly Father. He dies a painful and humiliating death.

Had you and I been at Calvary on that dark day in 33 A.D., would we not behold with bemusement the moderns who call such a macabre sight “good”?

Several years ago, a Catholic friend recommended that I read a book that helps answer this question. Death on a Friday Afternoon is an extended meditation on Christ’s last words from the cross. The text was penned by Richard John Neuhaus (a former Catholic priest and founder of First Things magazine). Chapter 4 focuses on Christ’s derelict plea, “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?” Neuhaus gives two important reasons why the crucifixion of the Christ is, despite its horror, the most hopeful of things to consider.

First, Neuhaus points to the 20th century’s version of the cross—the Holocaust. If a common morality in the modern world exists, it is this: Almost everyone agrees that Hitler’s atrocities are a suitable reference point for defining evil. But Neuhaus warns against placing anything aside from Christ as our moral guide. “[The Holocaust] is a cross without Christ, which makes all the difference,” Neuhaus writes. “The cross is not simply the horror and the tragedy and the pity of it all. It is the death of this specific man, who is God and who therefore undergoes in his death every death” (italics added).

Second, Neuhaus says that contemplating the crucifixion helps us “imagine the worst” and to realize that “the worst that could possibly happen has already happened”—namely, the death of the Savior. Thus, Neuhaus extends an invitation (one that some Christians might find strange). “We are tempted to rush to Easter,” he says of the desire to move quickly past Friday’s anniversary of death towards Sunday’s promise of rebirth. While understandable, he encourages people instead to “stay a while by the cross.” To cultivate a deeper knowledge, a richer empathy, and a more meaningful life of prayer requires, in his view, “that we attend to the scream that goes on and on, Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?” Even a glimpse of such deliverance is enough to move our hearts to sing.

With a better understanding of the events on Calvary, this is an appealing invitation with important prophetic company.

Paul simplified his preaching to the Corinthians around one thing: “Jesus Christ, and him crucified.” Nephi in the Book of Mormon confirms that it was “upon the cross” that the Christ was “slain for the sins of the world.” Joseph Smith said of his nascent church in 1838 that “the fundamental principles of our religion [are] the testimony of the apostles and prophets concerning Jesus Christ, ‘that he died, was buried, and rose again the third day, and ascended up into heaven.’”

Crosses are things we should want to see more of. They are reminders—on Good Friday and every other day—that a God was slain upon a cross 2,000 years ago to help you and me be freed of our onerous burdens. Even a glimpse of such deliverance is enough to move our hearts to sing, with Bunyan’s Christian,

Blest Cross! blest Sepulcher! blest rather be

The Man that there was put to shame for me.