Imagine two brothers—or else don’t imagine; maybe you’ve met them.

One finished college and took off for business school, or Teach for America, or a commission in the Marines. Now he’s back in his hometown and helping run the local police department/credit union/ACLU chapter. His hobbies include cheering at little league/soccer/chess tournaments and caring for his aging mother/disabled brother/wife battling depression. He’s a lay advisor in the local parish, where he leads the men’s prayer group. He’s owned the same house for ten years and the same car for twenty.

His brother founded a tech startup or produced a low-budget blockbuster or just won the lottery; whatever it was, it made him independently wealthy at 26. Now he wakes up every morning (well, maybe afternoon) and does literally whatever he feels like. Some days he stays in bed until dinnertime, some days he’s touched three continents by then; sometimes he lives the Tinder life and sometimes he settles down and gets domestic for a year or two. He lives in hotels and has movers on speed dial. When a salesman told him that some car company would let him change cars twice a weekend for $2,000 a month, he signed up without asking which company it was.

When the mood strikes, he goes to mass; sometimes even to confession. It’s easier when you never see the same priest twice.

The brothers see each other at Thanksgiving and Christmas, and each dreams at times of living the other’s life. “I could find a new job—make more money, drive a Beemer, travel more,” the first one thinks, “and I’m a handsome guy. I’m sure I could still play the field.” The second brother has, occasionally, all the longings you might imagine: a boy to teach to throw a ball, a woman to grow old with, a place to go where everybody knows your name and says nice things behind your back.

But neither brother actually tries to imitate the other. The first one knows what would follow: heartbreak for his wife, turmoil for his kids, friends disowning him, a stern-faced judge ordering child support—his name and legacy forever ruined among all the people he’s ever cared about. And if he’s honest with himself, he isn’t that handsome and probably couldn’t make more money. But he knows he chose a very good life; if he can no longer realistically choose a worse one, that’s not actually a problem.

The second brother never decides against trying the first brother’s life. He just never tries it, or not for long. There’s always a flight to Bali waiting, or a new bar in SoHo, or an exclusive fundraiser for that cause or candidate he believes in—and after that there will be time to think about things. If he decides a family is what he really wants, he’ll have one. Certainly he has no commitments that would keep him from it.

Maybe you think it’s obvious which of the brothers is happier or more fortunate or a better person. But which of them is more free?

According to Patrick Deneen’s book Why Liberalism Failed, it’s the first brother, but America thinks it’s the second. And that, he says, is what’s wrong with the country.

Ancient and medieval philosophers understood liberty as self-government.

Deneen writes that ancient and medieval philosophers understood liberty as self-government. Our first brother rules himself—he voluntarily conforms to the limits imposed by his nature, his community, and the environment—so he’s free. Our second brother is ruled by every passing urge, so he’s a slave.

What Deneen means by “liberalism” is the belief that the second brother is free, and he gives it a long and illustrious intellectual history. His key player is Thomas Hobbes, who advocated absolute monarchy by appealing to an imagined “state of nature.” In Hobbes’ state of nature, isolated individuals—lacking laws, clans, religions, or any other way to achieve peace and security—prey on each other endlessly, making life (in the famous words) “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

To escape this state of nature, Hobbes concluded, people would freely submit to an absolute monarch. Later thinkers rejected his conclusion but often imitated his method. Like Hobbes, they began their political theories by imagining rootless abstract individuals, often in a state of nature or something like it. Like Hobbes, they debated what sort of government their individuals would choose, claiming that because the individuals were not biased by particular histories, geographies, or theologies, whatever they chose would be universally valid.

The thinkers’ method became their result. They’d set out to design a government for real people, but inevitably, the real people whom their governments best suited were the ones most like their rootless imaginary individuals. Some thinkers decided this was a good thing—in fact, they decided, if real people weren’t like their imaginary ones, government should help them cut their roots and become that way. And help them it did, over and over again:

- welfare and social security programs freed individuals from dependence on their families and communities;

- government-supported railways, highways, and airlines freed them from their hometowns;

- government support for interstate and international trade freed them to compete on global markets—or in fact forced them to go compete on global markets, since it often destroyed their native communities and traditional livelihoods;

- government-controlled schools homogenized their education and pasteurized it, too, killing the religious and moral instruction to which the old schools had subjected them;

- new human rights, enforced by courts, freed them from their communities’ rules regarding sex, race, religion, language, and personal conduct.

And so on. In these ways and many others, big government is not the enemy of individual choice, but its bodyguard and bankroller.

All this freedom of choice causes problems; pretty much every problem, if you ask Deneen. Deneen blames it for sexual license, family disintegration, and mass loneliness. Its need for ever-expanding options drives both environmental degradation and the federal debt. It destroys the liberal arts because they (used to) teach people to bridle their passions, and modern man won’t be bridled even if he holds the reins himself. This leaves colleges nothing to do but worship wealth and power and help their students do the same. Freedom of choice even causes our new social stratification by justifying further growth at the commanding heights of government, business, and academia. These artificial Everests draw social climbers from all the local promontories they used to occupy, and eventually we are ruled by a class of hereditary meritocrats—often generations removed from their native soils and traditions—who almost can’t imagine any meaning to life beyond advancing either the liberal project or themselves.

All this freedom of choice causes problems; pretty much every problem, if you ask Deneen. Deneen blames it for sexual license, family disintegration, and mass loneliness.

So that’s Deneen’s message. Misled by the modern idea of liberty, we empowered big government, big science, and big business to liberate us from our limits. They did what we told them to, and yet nobody’s very happy about the consequences. We can’t solve our problems with more of the same, but we also can’t just turn back the clock. We must turn instead to . . .

To . . .

. . . well, Deneen won’t say. He tells us to practice good home economics, love our neighbors, and await some new dispensation—basically, it’s a Benedict Option without religion. Deneen defends his reticence, saying that good political thought isn’t ideological; we can’t make a better political order just by inventing some better theory; we have to build better communities, and then a better set of political ideas will naturally emerge.

But can Deneen honestly make that argument? After he spends most of the book arguing that a bad theory caused our problems, are we to take him seriously when he says we don’t urgently need a better theory? And how exactly are we to build better communities if our only viable political ideas are the ones that got us into this mess?

On the other hand, you might fairly wonder, was it actually ideas that made the mess, or was it something else? If better political ideas might bubble up from better communities, then perhaps our communities rotted on their own, and the sort of liberalism Deneen attacks is just the smell.

After all, why did America embrace the sort of liberalism it did? There were other options, as Deneen well knows, and there are still other options. A classical liberal who makes it to the end of Deneen’s book is bound to have lectured him silently a dozen times, “But my ideology is against government limits on individual choice, not private limits and certainly not self-restraint!” Indeed many conservatives support a classical-style liberalism precisely to prevent the sort of government interference with families, churches, and communities that Deneen presents as all liberalisms’ necessary consequence. Even progressive liberalism need not have reached its current conclusions. There have been starts in other directions; roads not traveled; brilliant thinkers whose ideas didn’t win out. There were choices made here, not just the inexorable working-out of liberalism’s initial idea.

But the choices really were made—Deneen’s not wrong about that. If you consider yourself a liberal and disagree with Deneen’s depiction of liberalism, you should ask yourself why his version of liberalism has been so much more successful than yours. Why is it, in so many political conflicts of the last fifty years, the party advancing our second brother’s interests won out? The left wanted to redistribute his wealth, and the right mostly stopped them; the right wanted (once upon a time) to restrict his sexual freedom, but the left stopped that. The bottom-right quadrant of American voters, the one that’s socially liberal and economically conservative, is by far the least populous, and yet in the long run, under both parties, it has mostly gotten what it wants.

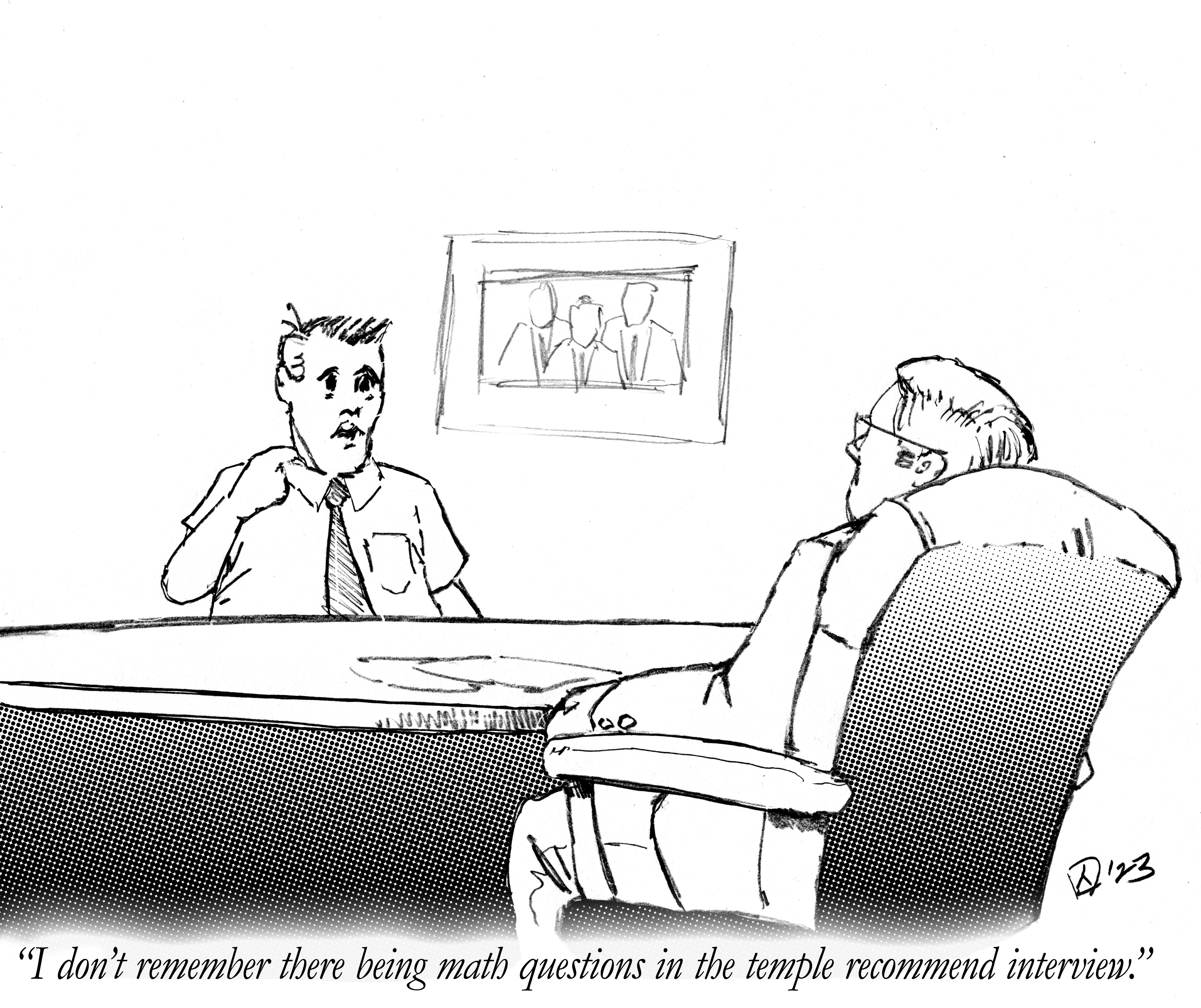

Why and how should we choose to be bound, restricted, constrained?

If you, like Deneen, dislike that outcome, perhaps you should take up the question Deneen avoids: why should we choose some sort of freedom other than the second brother’s? More bluntly, why and how should we choose to be bound, restricted, constrained? Deneen makes no argument beyond claiming it isn’t possible to have modern freedom without social dysfunction and, ultimately, environmental collapse. But why not? “X isn’t possible” is essentially a technological argument, and our society has long been trained to respond, “Yes, it is; I’m sure scientists are already working on it.”

Where is Deneen’s moral defense of limits—of virtue and the self-limitation it requires? Where, ultimately, is a defense of the first brother’s freedom and the ancient notion of liberty as self-government? That notion is at the very heart of Deneen’s book, since he uses it to prove freedom isn’t necessarily what modern Americans think it is. And yet, I have literally said more about the ancient understanding of freedom in this review than Deneen does in his entire book. He tells us at great length why modern liberty is bad, but he never actually argues that ancient liberty is better.

He never tells us why, if we must constantly deny ourselves things we want, and ask the law and our peers to punish us if we succumb—why we should call that state of affairs “freedom.”

The two brothers never change, by the way. The first brother never drives a nice car and never travels. One by one he sacrifices his dreams for his family and tells himself their gratitude is worth it. The second brother has a tremendous amount of fun, but never a wife or kids, so when the time comes for a nursing home he rents the room next door to brother number one. Nobody visits either of them. The first brother’s kids would like to, of course, but they live far away and you know how busy life gets.

They swap stories and ask each other, “Would you do it all again?”

If we as a society can’t explain why the first brother should say “yes,” and the second brother “no,” then we’re lost, and we deserve to be.