“St. Francis in Meditation” by Francisco de Zurbarán (1635-39)

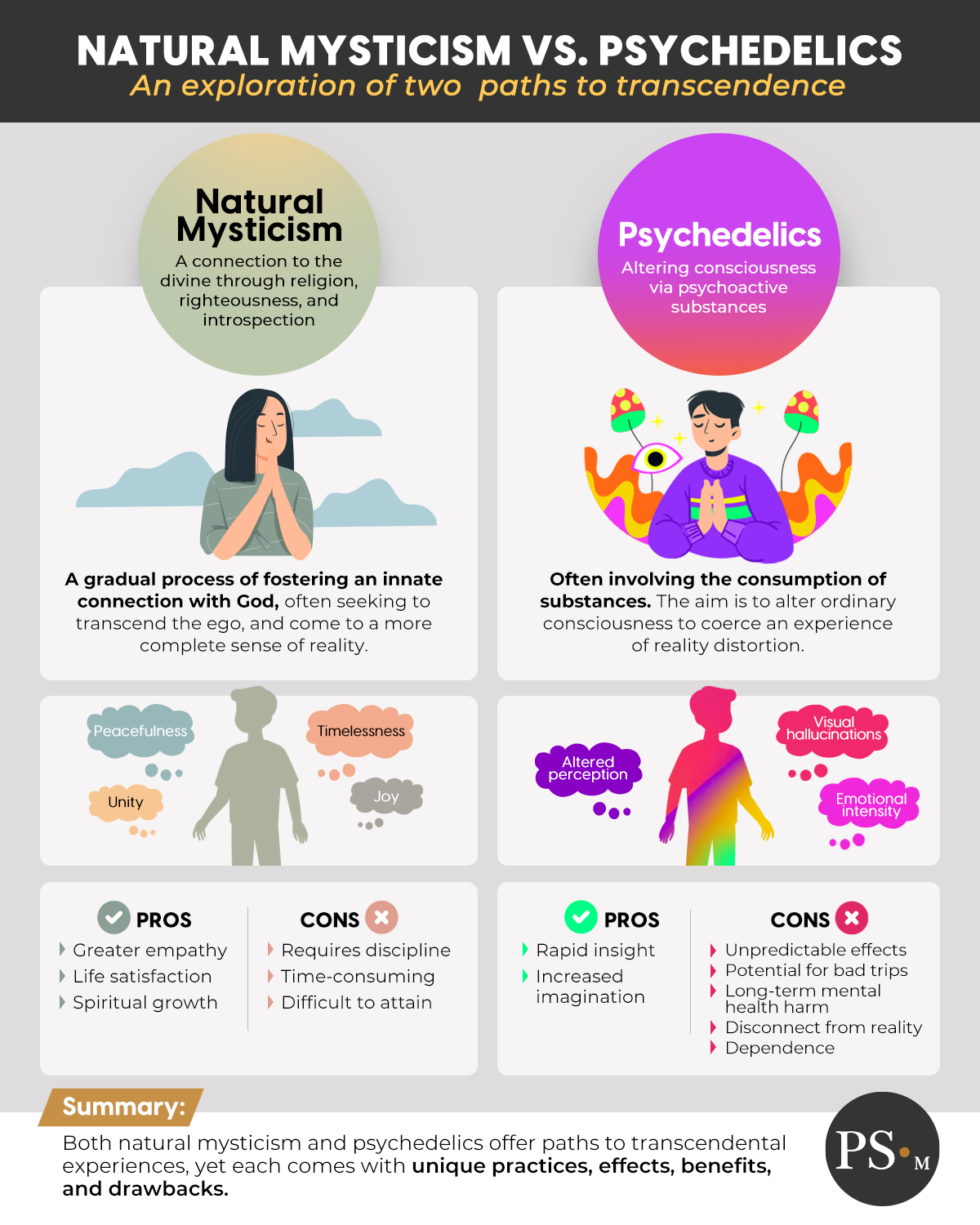

Mysticism is the pursuit of direct encounter with God. Mystical experiences were the animating reality that drove biblical prophets to establish the covenant people Israel and led to the biblical faiths that have shaped world history. When people of faith contemplate some of the more dramatic stories told by mystics, we often respond with envy, yearning for that personal experience of seeing God or hearing God’s voice. In its promise of transcendence, mysticism differs strongly from Western religious tendencies toward therapeutic self-worship on the one hand and notions of God derived entirely from human reason on the other.

The experience of Thomas Aquinas is illustrative: Aquinas wrote the Summa Theologiae, a 5-volume work of over 3,000 pages, regarded as one of the most influential works of theology in Western civilization. But Summa Theologiae remains unfinished since 1485 because, toward the end of his writing, Aquinas had a direct experience of God. He told his secretary, “The end of my labors has come. All I have written appears to be as so much straw after the things that have been revealed to me.” Aquinas stopped his greatest project and died three months later. Before his death, Aquinas did not repudiate his voluminous writings about God, but his inability to bring Summa Theologiae to completion suggests that Aquinas’ direct experience of God removed his interest in attempting to explain God through processes of human reason. Insist that the mystical entities get specific.

Psychedelic substances have always had an underground following, but in recent years, new narratives have called into question our legal prohibition of psychedelics in broader society. Michael Pollan, for example, argues for the benefits of psychedelics in his 2018 book How to Change Your Mind, which became a Netflix series. Proponents such as Pollan argue that micro-dosing and other procedures can minimize the possibility of harm with psychedelic use while enabling users to experience the mental and emotional benefits of these experiences.

Headlines such as the rise of a Magic Mushroom Church can lead to confusion among believers, who often end up asking hard questions: are the mystical experiences in scripture and other sacred history simply the product of chemical processes in the brain? Are the users of psychedelics having authentic experiences of God without the intensive demands of living a life of faith? How do we evaluate claims that arise from the context of psychedelic usage versus chemical-free natural mysticism that we find in the church? And perhaps the most burning of questions: are my own mystical experiences real, or are they things that can be replicated by ingesting chemicals?

Specificity in Latter-day Saint Mysticism

Latter-day Saint mysticism is unique in several ways; among those is our belief in the veil, a divinely-imposed limit of perception that prevents us from seeing and hearing spiritual dimensions of reality. We understand that the veil is intended to enable authentic choices between good and evil in a mortal experience that includes some exposure to both God’s soul-ordering influence and Satan’s chaos. But scripture and other sources are vague as to the exact nature of the veil, whether it is a biochemical mechanism or something else.

Latter-day Saint mysticism includes experiences described as a “parting of the veil,” or a temporary suspension of its perception-limiting influence, during moments of revelation, during temple service, in situations of crisis, and sometimes near death. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there were numerous public accounts of COVID patients in critical care either seeing or feeling the presence of deceased relatives, and these were commonly dismissed as hallucinations and delirium. But as Latter-day Saints, we had a very different response to reports of visitations of ancestors: they made perfect sense. For example, President Nelson’s clever suggestion of his late wife and daughter receiving a “hall pass” to attend his birthday celebration was a typical expression of what we envision about the afterlife. Among Latter-day Saints who know our spiritual heritage, there is nothing unusual about stories like these.

Under the influence of psychedelics, some people likewise report contact with specific beings who are not perceptible under normal circumstances. It is possible for Latter-day Saints to envision a number of explanations for these accounts: they might be figments of the user’s temporarily-heightened imagination, or they might be, as users claim, legitimately real beings who become perceptible through a momentary shift in brain chemistry.

Before we entertain the idea of a chemically-induced “parting of the veil,” however, it might help to consider Scott Alexander’s 2015 essay on psychedelics, published on Slate Star Codex. It has the most interesting of openings:

“Universal love,” said the cactus person.

“Transcendent joy,” said the big green bat.

“Right,” I said. “I’m absolutely in favor of both those things. But before we go any further, could you tell me the two prime factors of 1,522,605,027, 922,533,360, 535,618,378, 132,637,429, 718,068,114, 961,380,688, 657,908,494, 580,122,963, 258,952,897, 654,000,350, 692,006,139?”

For people who claim to be encountering real entities in their chemically-induced psychedelic trips, Scott Alexander is humorously suggesting an interesting test: if those entities are, in fact, real, then insist that the mystical entities get specific.

Specificity is a key way that we, as Latter-day Saints, discern authentic experiences of God and God’s influence versus any number of biochemical and other counterfeits. Sometimes authentic mystical experiences are vague, but in many instances, they are the opposite. For Latter-day Saints, revelatory experiences are often specific and actionable: exact names and details and resources revealed in family history work; exact locations of temple sites; promptings of exact places to go at precise times, people to speak with, words to communicate, and more.

Exemplifying Latter-day Saint mysticism, President Marion G. Romney once said of fasting:

I have had problems that did not seem to have a solution, and I have suffered in facing them until it seemed that I could not go further if I did not have an answer to them. After much praying, and on many occasions fasting for a day, a week, over long periods of time, I have had answers revealed to my mind in finished sentences. I have heard the voice of God in my mind, and I know his words.

What President Romney describes is echoed in scripture; think, for example, of the extremely specific and actionable revelation from the risen Christ that led Ananaias to take in and care for a shocked and devastated Saul of Tarsus. Specificity has long been a hallmark of ancient Christian and modern restoration mysticism into the present day, with countless personal stories among Latter-day Saints shared in publications like the Liahona and in our local meetings. And on a practical note, President Romney’s testimony suggests that it’s always a good idea to take with a grain of salt the claims of mysticism among former Christians who never seriously applied themselves to learn the spiritual discipline of fasting.

Ego Death

The psychedelic community claims another interesting phenomenon that some regard as “mystical” in nature, an experience that its practitioners refer to as “ego death.” The experience is described as a forgetting of one’s sense of self; people sometimes have out-of-body sensations and become unaware of their own names and other distinctive elements of existence. What sometimes follows is a sense that “everything is connected,” but in what sense everything is connected is left vague.

The problem with the notion of psychedelic-induced “ego death” was captured well in a Vice article by James Nolan that offered a glimpse into the online culture that has emerged surrounding the experience. One user describes the aftermath of chemically induced “ego death” gone awry:

Tony developed even stronger symptoms, saying that just existing in his body became so taxing that one night he literally got sick. “I had to look at myself in the mirror for a long time so I’d know what my face looks like,” he explains. “I had to tell myself my name over and over again until I started to develop a sense of identity. I saw how temporary this world is and I struggled to find a reason to live.”

Reflecting upon the accounts in the article, Nolan notices a searing irony: the pursuit of ego death, and the energetic frenzy of activity surrounding the experience, are very much ego-driven. Rather than diminish their sense of self, people seeking chemically-induced “ego-death” often end up more obsessed with the self, not less. Nolan concludes:

Certainly, when read about online, ego death seems to offer solutions to many of life’s problems – along with a promise of clarity in a confusing age – but with validation-seeking forum posts showing that, clearly, our egos can’t be killed for long, perhaps making friends with the ego, and learning how to control it, would be healthier than trying to destroy it.

In concluding that “clearly, our egos can’t be killed for long…” Nolan acknowledges that “ego death” is a misnomer. A better descriptor of this variety of psychedelic experience might be a temporary, chemically-induced suspension of brain functions that maintain a distinctive sense of self.

Buddhism maintains that the ego is a source of suffering, but Buddhism differs from the psychedelic gospel as to what should be done about it. In Buddhist thought, the power of the ego can be diminished, but not through ingesting chemical substances. Rather, Buddhism offers mindfulness and other practices designed to facilitate a voluntary letting go of the ego instead of ingesting chemicals in an attempt to force its temporary suspension. In Buddhism, three powerful “poisons” of delusion, craving, and hatred are manifestations of the ego and its tendency to increase our self-generated suffering. Authentic spirituality is about letting go.

It is true that there are numerous credible claims of how people have benefited from the use of psychedelics: claims of real turnaround in depressive episodes and the opening of the mind to new and better ways of processing life experiences. This has led to a proliferation of calls for formal recognition of their therapeutic value and legalization of their use.

A common thread in these stories of the beneficial use of psychedelics is that they enable users to transcend deep and rigid mental conditioning, which is why there are so many stories emerging from military and ex-religious communities. In his interview on the Shawn Ryan Show (listener warning: profane language), U.S. Marine sniper Cody Alford recalls his use of psychedelics after his long military career.

Alford’s experiences did seem to help him to see that he had been navigating life with very little internal autonomy, only ever reacting with conditioned responses to the world around him. Psychedelics were not the answer to his problems, but they seem to have facilitated an important disruption of his conditioning. This enabled him to ask basic foundational questions about his identity and values, questions he had avoided all his life. In discussions of the impact of psychedelics, these transformations are often taken to be evidence that psychedelics facilitate neuroplasticity or rewiring of the brain to accommodate new possibilities in how we engage with the world.

But for each of these, there are plenty of claims of benefit that are belied by observed reality: people using psychedelics as a perpetual coping mechanism for the results of poor life choices or as a tool to avoid the discomfort of living in reality. When someone claims profound wellness benefits from psychedelic experiences, we should expect to see those mushrooms being used as something other than an avoidance mechanism or a numbing agent for the pain of nihilism. And yet those are patterns of use that we commonly observe.

Could these kinds of beneficial transformations occur without psychedelics?

Psychedelic user Scott Locklin thinks so:

I’d argue that the types of improvements in outlook measured as a positive outcome of psychedelic use would be similar for any novel, extreme and unfamiliar experience; most of which are less obviously bad for you …

People who use the things on a regular basis think they bring back profound insights, because the drugs make looking at a flower feel profound. Yet, the actual insights brought back by people on their “trips” tend to be the type of thing a bit of self-reflection would take care of … I’ve yet to hear of any sort of improvement in creativity or even a single interesting idea anyone has ever brought back from psychedelics.

Non-chemically aided mysticism can produce the same benefits described by users of psychedelics. I have a close friend who, following a long and difficult military career, turned to cycling and fly fishing. He related to me that cycling, traveling alone in silence for long hours over distances with a constant pedaling muscle cadence, has allowed him to “work out his demons.” Fly fishing has put him into nature, where weather and other variables are not responsive in any way to the human ego. Another friend with a long military career with numerous combat deployments told me that he has been transformed by serving in church as a primary teacher, where every week, the music and lessons for children center on very basic healing realities of the gospel.

Mindfulness silence retreats are transformative in many instances; spending a week or more without electronic stimuli and without speaking to other people is something that many have experienced as profoundly disruptive to their unhealthy egocentric patterns of thought and feeling. Changes of pace, changes of environment, and personal service to the disadvantaged are all catalysts to healing breakthroughs in how we process the world.

And authentic spirituality is about letting go as much as it is about attempting to obtain things. A tremendous amount of healing comes from relinquishing our insistence upon control—our egocentric desire to make the world reflect our will. I suspect that a significant amount of healing reported from the use of psychedelics comes from the fact that they temporarily suspend our ability to impose any meaningful amount of control upon our experience. Psychedelics momentarily invite an important experience of surrender that Christian mystics have long sought through non-chemical means. Natural mysticism is really the only mysticism.