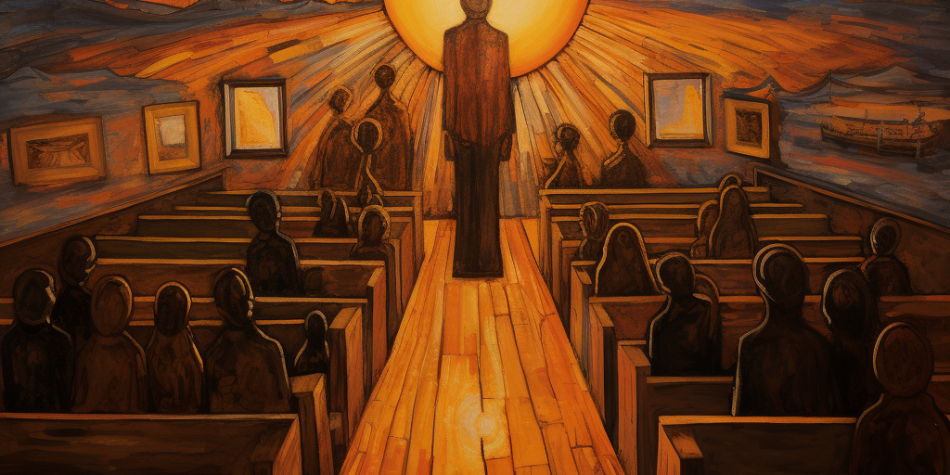

In the realm of faith, as in nature, autumnal hues often preface a period of apparent decline. Recent discussions center on a purported decrease in membership numbers within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the United States, eliciting varied reactions from concern to gloom and even outright derision in some corners. It’s a narrative that fits neatly into a larger tale of dwindling religiosity in America, a tale often spun with a not-so-subtle thread of triumphalism.

But the Latter-day Saint story, like any narrative worth its divine salt, is rich and multi-dimensional. Truth is not a popularity contest, and changes in membership (positive or negative) are not by themselves a barometer of God’s approval. This piece aims to explore these membership trends, not with a sense of denial or desperation but with a clear-eyed recognition of the complexity and with faith in the Church’s divine mandate. We’ll delve into a fuller context, one that sustains the truthfulness of Latter-day Saint teachings while offering insight into how we might navigate these changes positively. For in the grand mosaic of the unfolding restoration, these shifts may be less of an end and more of a vital, transformative beginning.

Examining the numbers

Before we delve deeper into this narrative, it is essential to examine the numerical dynamics at play in a more nuanced way. The recent conversation has centered around an article published in the Washington Post.

The article was focused on politics, so it didn’t give much attention to the underlying data. The article reported that the number of self-reported Latter-day Saints in the United States has dropped by one million adult members over 15 years. Though this number may be imprecise, trusted demographer and data analyst Stephen Cranney writes that the trend is real. Truth is not a popularity contest.

The larger consideration is that while there may be fewer US-based Latter-day Saints, the Church is still continuing to grow.

The framing of the issue demands a more global perspective. The Church’s presence extends beyond American borders, and it is essential to understand the international growth in this context. The Church is experiencing growth in regions such as Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia. It is a global body of believers, and the flow of numbers in one region or another does not encapsulate the entirety of its growth narrative.

What, then, does this international growth mean for the church community? First and foremost, it reflects the fulfillment of the Lord’s promise that the gospel shall be preached “to every nation, and kindred, and tongue, and people,” and perhaps another manifestation of the Lord’s vision that “the last shall be first, and the first last.” The Church’s expanding international footprint should inspire us with a sense of progress and purpose. We are participating in the unfolding of a divine plan, and that plan is not predicated on maintaining a specific percentage of believers in one nation but on the spread of truth and light to every corner of the earth.

Reframing Church Health: Beyond Numbers

Perhaps, more importantly, however, the tendency to view church health through the singular lens of numerical strength is, while understandable, to some extent, misleading. After all, we live in a world that worships quantifiable metrics, and numbers, in their stark absolutism, offer a tantalizing illusion of unambiguous objectivity. Yet, as Latter-day Saints, we understand that the most significant truths elude simplistic measurements. Periods of ‘falling away’ or decline are an expected.

In our modern society, it’s all too common to measure success in terms of grandiosity, volume, and viral potential. We may unconsciously transfer these metrics onto our understanding of God’s kingdom, equating numeric growth with divine approval. But such a metric becomes deeply flawed when viewed through the lens of the Gospel and the historical record of God’s dealings with His children.

Take, for example, the prophet Noah. By the world’s standards, his 120-year-long preaching effort would seem a dismal failure, persuading only his immediate family to join him in the ark. But in the heavenly ledger, Noah’s faithfulness, not the number of his followers, defined his success. Abinadi’s story offers a similar message.

And let’s not forget Elijah, who felt alone in his prophetic calling until God revealed that seven thousand faithful individuals were yet in Israel.

This principle underscores the broader divine mandate that Latter-day Saints believe they are entrusted with. We don’t merely belong to an organization seeking to increase its membership but to a divinely commissioned Church with the mission to “invite all to come unto Christ.” This commission is ours to fulfill, no matter how many of those accept that invitation along the way.

Alongside numerical growth, we must value the quality of fellowship, the depth of scriptural understanding, and the impact of service and outreach programs. The strength of a Church is more meaningfully gauged by the spiritual resilience of its members, the integrity of its families, and the intensity of its light in an often dim world. These factors, perhaps summarized as “conversion,” are left out of the social science research on these questions.

And if we use these metrics, we may find that the Church of Jesus Christ is more robust and radiant than we ever imagined.

Scriptural Perspectives

To truly understand these membership shifts within the Church, we need to draw on the wisdom offered in the ancient scriptures. This is far from the only period in history where the Church has faced significant cultural headwinds.

The prophecy that the stone would fill the whole earth did not include that it would do so at an exponential or consistent growth rate. A testimony of the restored gospel has never been predicated on its worldly popularity. Nor does the prophecy that the kingdom shall not be destroyed promise it will never ebb.

Much to the contrary, scripture is replete with suggestions that even the final dispensation will not be an uninterrupted period of growth.

The allegory of the olive tree from Jacob 5 in the Book of Mormon covers a broad sweep of history, from the House of Israel’s earliest days to the end times. One of the critical themes is that of periods of growth and decay. Throughout the allegory, the master of the vineyard and his servants diligently work to preserve and nourish the trees, but despite their best efforts, there are times when branches wither, decay, and fall away.

In verses sixty-nine and seventy-three, we see that even in the final season of restoring the tree, there is a plan that bad fruit will grow and need to be cast off, and it occurs precisely as planned. The lord of the vineyard says that the final season included both a time of nourishment and a time of pruning. A period of winnowing can be a period of great strengthening.

Meaningfully, when Gideon prepared to fight the Midianites, God reduced his army to a mere 300 men to demonstrate that victory was not dependent on numbers but on divine power. A period of winnowing can be a period of great strengthening of faith and courage amid those that remain. Jesus miraculously fed 5,000 with only a few loaves and fish.

Smaller numbers do not imply a lack of divine favor or power, nor are they contrary to God’s plan. Rather, they often set the stage for divine manifestations, resilience, steadfastness, and faith in times of adversity. The history of God’s dealings with His people is not a story of unimpeded growth but of oscillations, each pruning serving as a prelude to a new flow of spiritual power and enlightenment.

Even amid changing numbers, Latter-day Saints can see this period not as a setback but as an invitation to profound spiritual growth and renewal.

In these ways, a changing landscape need not erode our faith but can instead galvanize it. Just as precious metals are refined in the furnace, our collective faith can emerge stronger, more resilient, and more vibrant than before. Through this transformative process, we remain true to our divine mandate as Latter-day Saints, ever ready to serve, uplift, and illuminate the world.

The truth and vitality of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints does not rest on numbers. They are rooted in the individual and collective faithfulness, resilience, and spiritual growth of its members. We are reminded of Christ’s teaching “Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them.” For those of us in this portion of the Lord’s vineyard, population trends do not define nor diminish the Savior’s presence among His followers.