In our contemporary culture, therapy is often sought as a means of improving or cultivating an individual’s “self-love.” For many practitioners of psychotherapy, improving a client’s sense of self is a central feature of any therapeutic modality and a core essential “need.” Across a wide variety of theoretical orientations, seemingly limitless sources suggest different methods toward the cultivation of self-love. This movement and orientation should be of particular interest to Christians, whether they are the therapist or the client.

Self-love is hard to define, and when professionals make the attempt to do so, they often contradict one another. Definitions lie in great extremes, such as “treating oneself” with little restraint (often like a benevolent arrogance), to self-acceptance or self-discovery. When subscribing to such vague paradigms, this lack of clarity leads to difficult moral questions and possible negative consequences. What does self-love look like? And, how do you know when you love yourself enough? One therapist notes: “[self-love] sets you up to ring a high bell that’s unattainable, because loving yourself doesn’t come with a certificate or finish line.” What does self-love look like? And, how do you know when you love yourself enough?

However, many Christians will cite Jesus in the New Testament as evidence for this perspective. “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself,” has been frequently interpreted as the declaration that “you must love yourself before you can love others.” This idea seems appealing because it has significant support from therapists, influencers, and philosophers.

This is a serious assertion to consider. At the core, proponents of this view are saying that the capacity to love others is contingent on the level or quality of love for self. Such thinking invalidates nearly any effort or declaration of love offered by one who does not meet the proper criteria or threshold of self-love, ambiguous as that may be. After all, in our state of imperfections, would we ever be able to achieve a perfect state of loving oneself? And in subscribing to such ideas, could we ever then truly love someone else?

Rather than saying we need to love ourselves to love others, C.S. Lewis reversed these ideas in Mere Christianity by implying self-love is already a given in our humanness and that, rather than giving more attention to it, we need to give that love to others.

It is notable that the law to “love thy neighbor as thyself” also appears in the Old Testament in Leviticus 19:18, which was perhaps the point of reference for those in the New Testament. Consider the context of Christ’s reference as he was questioned by a lawyer about which is the greatest of the commandments. Perhaps this is part of the old law that He came to renew, as Christ later taught:

Ye have heard that it hath been said, Thou shalt love thy neighbour, and hate thine enemy. But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you; That ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven … For if ye love them which love you, what reward have ye? (Matthew 5:43-46).

Jesus seems to redirect the commandment from simply loving “as thyself” to instead loving beyond that, further, or more than yourself.

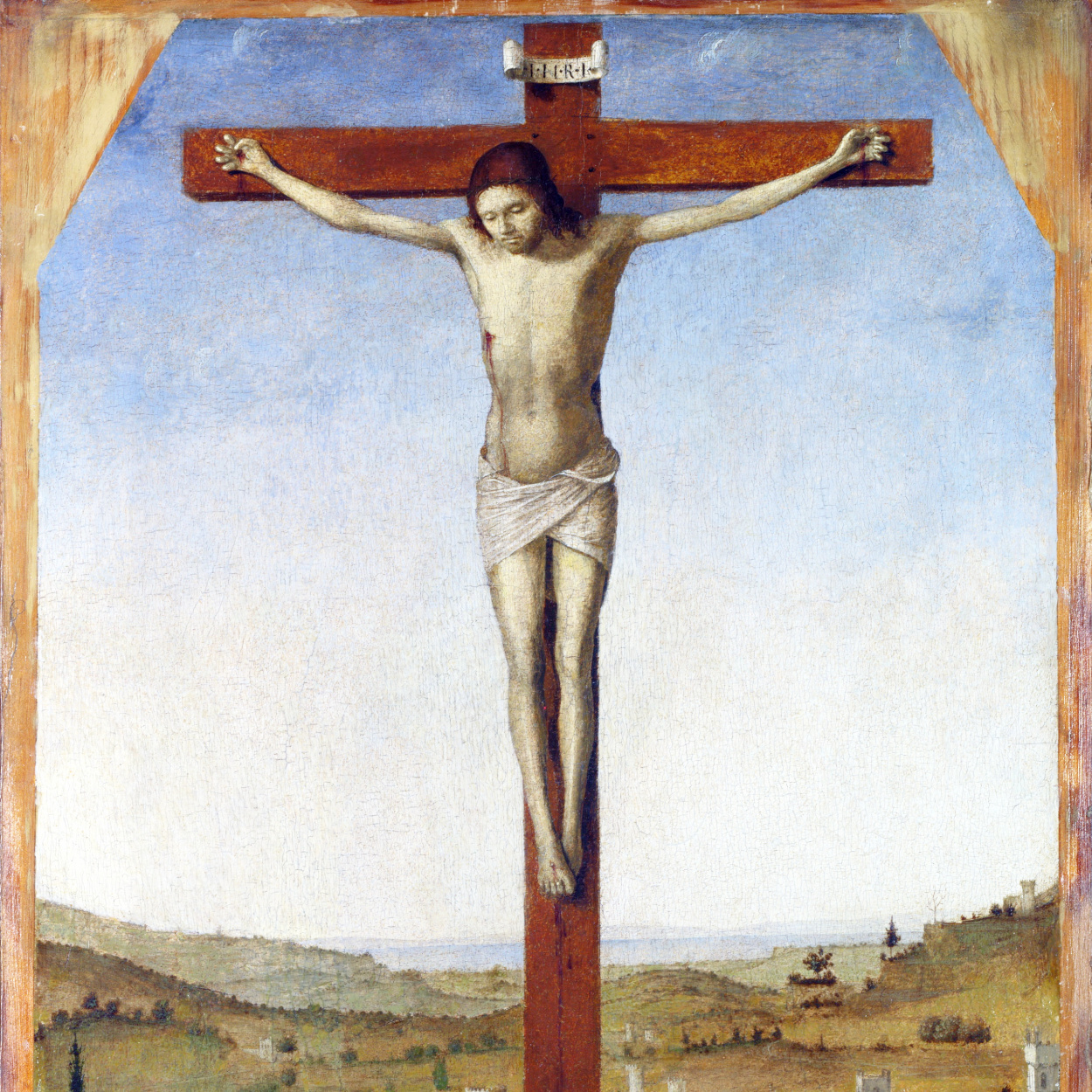

In response to those questioning Him, He explained the existing law was to love your neighbor as yourself. However, shortly before His sacrifice, He introduced a new, higher law that would distinguish His disciples: “A new commandment I give unto you, That ye love one another; as I have loved you, that ye also love one another” (John 13:34-35). This law is distinctively different from simply loving others as oneself.

In reality, Christ asked His disciples to look to Him as the reference of love, rather than to themselves. Additionally, He asserts an eternal truth regularly restated throughout scripture: “as I have loved you.” Christ first established that we are loved by Him and we are to show His love, not our own. Perhaps, with Jesus Christ fulfilling the law as was His role, from this new commandment we can understand “love thy neighbor as thyself” with new eyes: we are to love our neighbors as we are loved by Christ. It is only in relation to others that we are even able to form a sense of self.

While I’m certainly not advocating for self-deprivation as opposed to self-love, a focus on self-love has the tendency to further isolate those who could benefit from genuine interactions with others. When we explore self-love in a philosophical sense, it creates an understanding of self that is completely independent of other people. However, it is only in relation to others that we are even able to form a sense of self. A person’s individual cognition—or reason—does not hold the true reality of a self, as “it is not thought, but relations, the object or substance of thought, that is in the mind” (Houser, 1983, p. 345). By others, we are able to form a sense of self, the world is given meaning and form (Bergo, 2019; Vygotsky, 1997, p. 12). Fundamentally, human beings are relational beings, we form a distinct self because we are in relation to others.

When one understands oneself relationally, there are many alternatives available for a hopeless individual to find help and healing, particularly from a Christian perspective. No one has made it to where they are alone. There has always been a parent, a sibling, a friend, a teacher, a mentor, someone involved and invested in the individual’s life that contributes to a sense of belonging, a relationship of co-constitution, even if they may not recognize it. Fundamentally, as Christians, we believe God is always a person to whom we belong. Perhaps helping others become aware of the loving relationships around them is more helpful than encouraging strict self-reliance, which may result in isolating the individual even further. Rather than encouraging radical egocentrism, introducing new voices of love, broadening horizons of relationships, or practicing loving-kindness meditation can help liberate and expand the individual to a more integrated sense of self.

An example of turning outward for meaning rather than finding it within ourselves is found in an interaction between Dr. Whoolery and a student, taken from a presentation to the American University in Bulgaria:

I had a young man speak to me recently … Imagine yourself and his situation as he explained feelings of despair and hopelessness, not even sure that he thought life was worth living.

I asked him, “Why are you still alive?”

He said, “Well, I’d feel bad for my family.”

I said, “Well, why would you feel bad for your family?”

“Well, because they would be sad.”

“Why would they be sad?”

“Well, because they care about me.”

I said, “Okay, well, why would you feel bad for making them feel sad?”

“Well, because I care about them.”

And I said, “Love from your family and to your family seems like a good place to start your life, and I think it can form a basis for where you go from here” (TEDx Talks, 2024).

This is an excellent example of how a therapist may redirect their clients toward the loving relationships they may already have, especially toward Christ. In recognizing our love for others, we can also begin to recognize the love given to us by others. Such an orientation can allow people to live more in the world rather than within themselves. Additionally, by facilitating and encouraging relational connection, individuals can cultivate an awareness of their own support structure. Dr. Whoolery again proposes this type of awareness when he explored his own family dynamic and culture:

There are six of us in our family of four girls. If we each think about ourself, we have one person concerned about our needs. When we think about each other, we have five. So if she just thinks about everybody else and doesn’t worry about herself, everybody else is going to take care of her anyway (TEDx Talks, 2015).

Whether it is through biological family, found community, church, or any other kind of support system, we are stronger together than we are in isolation. In Western American culture, suffering often becomes an isolating experience. However, if we can shift in our understanding and realize we are necessarily linked and connected to others in meaningful ways, we can become aware of the fullness and love that surrounds us. In turn, we can extend such love to others who may be suffering, feeling isolated, or feeling unloved. Perhaps the simplest solution to self-love … is to simply cut the phrase in half: we need to practice love.

Perhaps the simplest solution to self-love—a concerning practice—is to simply cut the phrase in half: we need to practice love. Maintaining the simplicity of love allows us to locate reality in the between: between a person and the world, others, the past, and the future. Living a life relationally and open to others, yielding to the love given to us rather than living in an isolated shell, can liberate those seeking a more meaningful life and help us become ever more connected with God and those around us.