As new missionaries in the MTC, my companion and I were having one of those gospel discussions that happen so commonly among missionaries.

He didn’t like it when people said they knew God was real in their testimonies because he wondered how they could know without seeing God. The only way people could know God, he reasoned, was to have Jesus Christ Himself appear to the person. He also thought it was unlikely that all the people who claimed to know God had seen Him.

His reasoning continued that senior, prophetic leaders must have had a more sacred and direct experience with God—which allows them to be a special witness of Christ. Only they, he asserted, could truthfully proclaim that they know God is real. Our senses can be misleading.

Such were his words, and frankly, they made sense to me. How can you really know something if you’ve never seen it? Since I’ve never actually met our Lord personally, I guess I can only believe in Jesus Christ and hope that He’s real, right?

Except there’s one problem: my own experience told a different story. I knew that God was real and was my Father in Heaven. And I knew that Jesus Christ was real too. I couldn’t articulate at the time how I knew, but this made me realize that if I claimed to only believe in God—and tell others that I didn’t really know for sure—I would be lying to myself, to others, and to God.

Why do we rely on senses and reason? From where does this confusion arise? Maybe from the powerful idea that seeing is believing. We say this because we like to know things and need certainty to function in the world. And it’s usually pretty difficult to dispute what you can see with your own eyes unless you’re wandering in the desert looking for water (and even then, you’d probably trust a mirage that comes into view). We tend to trust our senses. And if we can see, hear, touch, taste, or smell something, then we like to believe that it’s something we can know for certain.

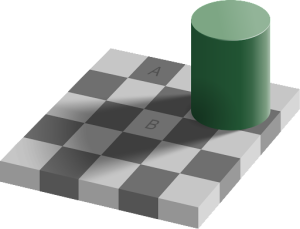

However, our senses can be misleading, as seen in examples like the mirage or the checker box illusion, where two squares may appear to be different colors but are not.

Furthermore, there are some things we can’t learn through our senses. Indeed, there are other forms of knowledge that can help where the senses are limited. Our own human reason is one such form of knowledge. We know that 2+2=4 because it just makes rational sense; we don’t have to conduct a scientific test to show it’s the case. belief can develop into an active faith. Belief can develop into an active faith.

Reason also has its limits, as demonstrated by the existence of paradoxes. Is the statement, “This statement is a lie,” true or false? While various philosophers have attempted to puzzle out the paradox, there is no question that it pushes up against the limits of reason.

Without diminishing the value of either sense or reason, something more may be needed. In this case, something more than reason and sensation alone may be needed. But are we open to that? While it’s true that trusting in both our senses and in our reason together generally leads to a better picture of the world than relying on just one or the other, what happens when we trust in both—and nothing more?

Seeing faith as an alternative to knowledge. It is often the case that faith today is typically seen as being secondary to both our senses and human reason. In fact, sometimes faith isn’t just seen as secondary to knowledge; it’s seen as the opposite of knowledge. Dr. Richard Williams, in a BYU devotional address, explained that:

The modern view is essentially that reason and logic ultimately ground knowledge and truth, whereas faith is what we are forced to rely on when we lack indubitable certainty. Faith, on this view, is a sort of positive thinking, what we cling to when we do not know.

In the modern view, faith is often seen as being the equivalent of belief, which itself is often seen as that thing we cling to when we don’t really know—mere opinion even. That’s essentially how my companion felt. To be clear, this does not suggest that belief is bad. On the contrary, a scriptural understanding of belief elevates it to a higher level than modern understanding does. The Savior has, on numerous occasions, praised people for believing, especially those who believed without first seeing. Consider the Savior’s words to the apostle Thomas:

Jesus saith unto him, Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed (emphasis added).

Although belief and faith are often considered the same, Latter-day Saints view faith as more than just belief while still appreciating belief. Latter-day Saint apostle David A. Bednar has taught:

A belief is simply anything we mentally or intellectually accept as true. For example, we believe and accept as true the nature of the Godhead as taught by the Prophet Joseph Smith. We believe and accept as true the restoration of the gospel in its fullness in these latter days. And, most importantly, we believe and accept as true the reality of the atoning sacrifice of the Redeemer. In summary, then, belief is the mental and intellectual acknowledgment, acceptance, and assent that something is true. Belief requires only the mind. Faith grows out of and builds upon belief and produces action.

Elder Bednar argues that seeing faith and belief as the same can hinder our progress as we assume there is nothing else to achieve. We may fail to appreciate how belief can develop into an active faith.

In the second part, I explain how faith can act as knowledge by bringing together our senses, reason, and belief to produce action.