Do you ever think new technologies are harmless, that time is cruel, that consciousness is nothing more than inner light, that community is burdensome, or that everyday life is meaningless? Perhaps these five books can convince you otherwise.

Amusing Ourselves to Death

Neil Postman

Whose dystopian prophecy was more accurate? Orwell’s 1984 or Huxley’s Brave New World? The answer, of course, depends on where one lives. For the United States and other wealthy Western nations, the answer is surely Huxley’s. This is the basis of Neil Postman’s book from 1985. The author explains:

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. … In the Huxleyan prophecy, Big Brother does not watch us, by his choice. We watch him, by ours.

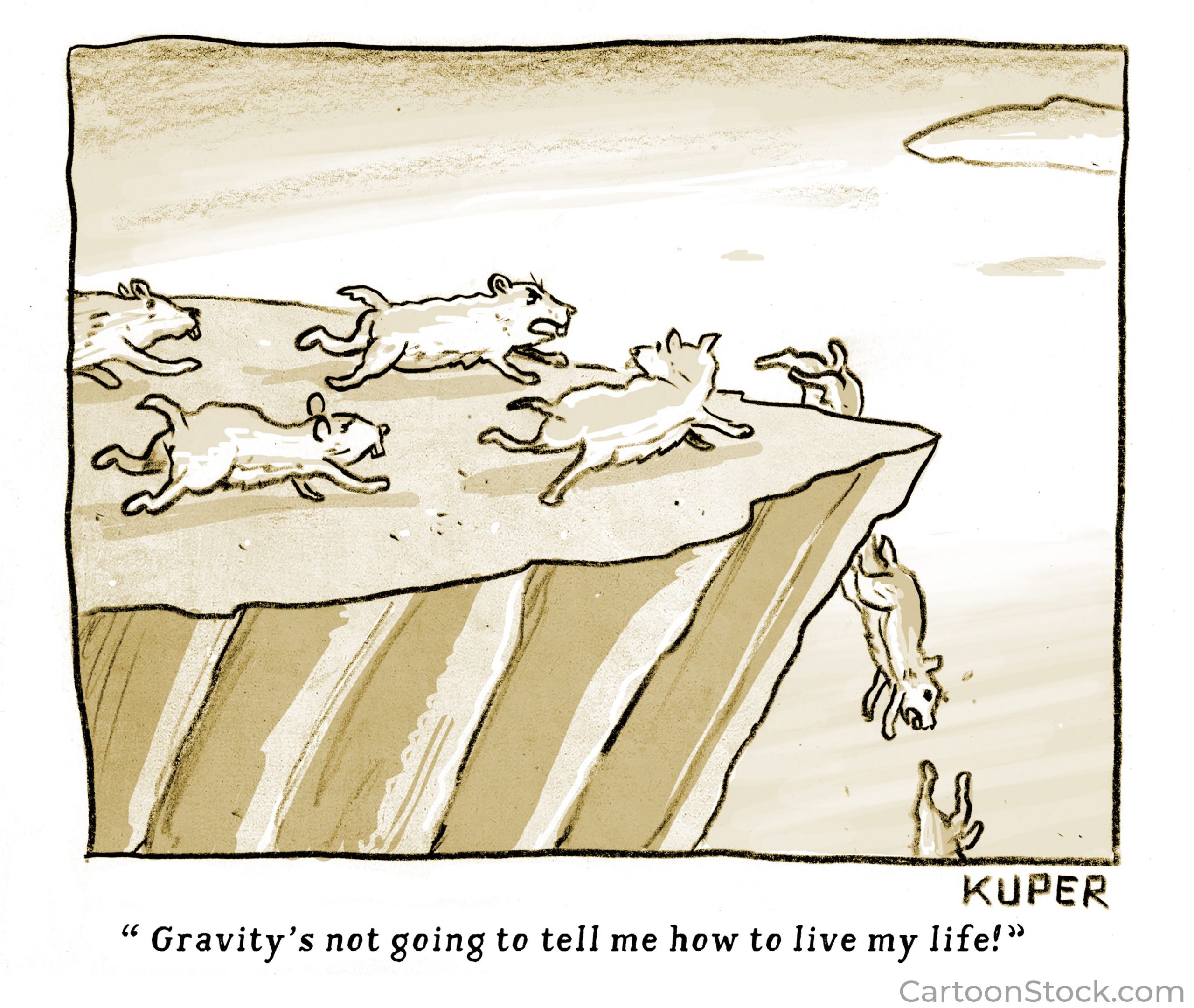

This short book takes on technology’s collective impact on our ability to think. Television—the kind with channels that had set schedules all day, every day—was then king of the communication landscape. Some may feel Postman’s arguments are nothing more than curmudgeonly longings for a bygone world. But through the eyes of this millennial, Postman’s persuasive words of wisdom prove plenty relevant for our time of self-centered discourse and infinite on-demand entertainment.

Postman’s analysis is measured. He is careful to note that technologies such as TV are not all bad. But he discourages thoughtless acceptance. New mediums of communication encourage “certain uses of the intellect, by favoring certain definitions of intelligence and wisdom, and by demanding a certain kind of content—in a phrase, by creating new forms of truth-telling.” We must remember, he says, that “in every tool we create, an idea is embedded that goes beyond the function of the thing itself.”

Jayber Crow

Wendell Berry

This is one Berry’s works about the fictional town of Port William, Kentucky. (The series can be read in any order.) The novel, a first-person narrative told by the town barber, Jayber Crow, touches on love, loss, the questioning life, the dangers of industrialization and consumerism, the need for deep covenantal relationships, and more.

The book brings a slow and steady comfort to the patient reader. The simple but majestic meditations from what Jayber witnesses and experiences in Port William are delicious and can be savored in repeated readings. A notable example: After one of the town’s sons dies in Vietnam, Jayber reflects on the cruel yet caring nature of time: “The mercy of the world is time. Time does not stop for love, but it does not stop for death and grief, either. After death and grief that (it seems) ought to have stopped the world, the world goes on. More things happen. And some of the things that happen are good. My life was changing now. It had to change. I am not going to say that it changed for the better. There was good in it as it was. But also there was good in it as it was going to be.”

Dr. Zhivago

Boris Pasternak

This novel is set between the 1905 Russian revolution and the Second World War. It is a story of love and longing, alongside the thoughtful and illuminating meditations from the life of the fictional poet-physician Yuri Zhivago.

A hefty insight comes early in Part 3. Yuri, in the mist of his studies to become a doctor, comes home to find his future mother-in-law sick. Others think she is deathly ill. She seeks Yuri’s reassurance because she fears what comes after death. Yuri launches into a kind of mini-sermon on death, consciousness, and resurrection.

“Will it be painful for you, does tissue feel its own disintegration? That is, in other words, what will become of your consciousness? But what is consciousness? Let’s look into it,” Yuri says. “To wish consciously to sleep means sure insomnia, the conscious attempt to feel the working of one’s own digestion means the sure upsetting of its nervous regulations. Consciousness is poison, a means of self-poisoning for the subject who applies it to himself. Consciousness is a light directed outwards, consciousness lights the way before us so that we don’t stumble. Consciousness is the lit headlights at the front of a moving locomotive. Turn their headlights inward and there will be catastrophe. … What do you remember about yourself, what part of your constitution have you been aware of? Your kidneys, liver, blood vessels? No, as far as you can remember, you’ve always found yourself in an external, active manifestation, in the work of your hands, in your family, in others. And now more attentively. Man in other people is man’s soul.”

Life Together

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Some, like me, prefer solitary to group life. Others, perhaps you, find energy in community with others. Bonhoeffer teaches us that Christian community needs both personality types (and all their varying shades) to be what it is called to be. “Only as we are within the fellowship can we be alone, and only he that is alone can live in the fellowship. Only in the fellowship do we learn to be rightly alone and only in aloneness do we learn to live rightly in the fellowship. It is not as though the one preceded the other; both begin at the same time, namely, with the call of Jesus Christ.”

Mere togetherness, though, is not enough. Authenticity and transparency are indispensable ingredients. “It may be that Christians, notwithstanding corporate worship, common prayer, and all their fellowship in service, may still be left to their loneliness.” Why? Because of the overpowering pull to appear perfect. “The pious fellowship permits no one to be a sinner. So everybody must conceal his sin from himself and from the fellowship. We dare not be sinners. Many Christians are unthinkably horrified when a real sinner is suddenly discovered among the righteous. So we remain alone with our sin, living in lies and hypocrisy. The fact is that we are sinners! … Sin demands to have a man by himself. It withdraws him from the community. The more isolated a person is, the more destructive will be the power of sin over him, and the more deeply he becomes involved in it, the more disastrous his isolation.”

This work comes out of Bonhoeffer’s experience living a common life with 25 other vicars in the Germany of the 1930s. Like him, we can learn that it is in our openness with each other that we experience “the presence of God in the reality of the other person.”

Liturgy of the Ordinary

Tish Harrison Warren

God is “over all and through all and in all” (Ephesians 4:6). This is both the witness of scripture and the message in this delightful little book from Anglican priest Tish Harrison Warren. She shows us how God refines us through the everyday acts of waking up, making the bed, brushing teeth, losing keys, eating leftovers, fighting with a spouse, checking email, sitting in traffic, calling a friend, drinking tea and sleeping.

Christians will find no better example of everyday goodness than the Being whom they worship, Warren says. Before He had performed a recorded miracle, it was this quotidian (to those who knew Him) Christ who was introduced by the Father as “my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased.”

“It would make more sense if the Father’s proud announcement came after something grand and glorious—the triumphant moment after feeding a multitude or the big reveal after Lazarus is raised,” she writes. “But after hearing about Jesus’ birth and a brief story about his boyhood, we find him again as a grown man at the banks of the Jordan. He’s one in a crowd, squinting in the sun, sand gritty between his toes. The one who is worthy of worship, glory, and fanfare spent decades in obscurity and ordinariness. As if the incarnation itself is not mind-bending enough, the incarnate God spent his days quietly, a man who went to work, got sleepy, and lived a pedestrian life among average people.”