One way to look at how ideas spread through society is to compare ideas competing with each other for believers to genes competing with each other for reproductive opportunities. This isn’t a new idea. It was most famously expressed by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene, for which he invented the term “meme.”

In his analogy, a meme is a unit of cultural information just as a gene is a unit of biological information. Memetics is the study of how memes spread just as genetics is the study of how genes spread. (These days a meme is just a funny picture with a witty caption, but even that sense of the word is derived from Dawkins’ original: the funnier the image is, the wider it spreads).

To elaborate the analogy, we have to ask what makes ideas well-adapted for transmission to new believers (in the same way that some genes are well-adapted for transmission to new generations). And that depends on the environment.

Presumptuous certainty is something we fabricate to appease our fear of ambiguity and uncertainty. We don’t really know. Not for sure. But we claim to anyway.

In my previous piece, I laid out the two human tendencies that influence the environment in which beliefs compete for adherents. First, we tend to believe what we would like to believe over what is true, especially in those arenas where there is little cost to incorrect beliefs and great benefit to self-serving ones. Second, we tend to invest these convenient beliefs with presumptuous certainty.

I say presumptuous certainty to differentiate this kind of willfully-asserted certainty from genuine conviction. Presumptuous certainty is something we fabricate to appease our fear of ambiguity and uncertainty. We don’t really know. Not for sure. But we claim to anyway. This presumptuous certainty is a function of pride, fear, or both, and it stands in stark contrast to genuine conviction, which arises naturally as a result of evidence, expertise, or spiritual experience, and is an expression of humility and courage.

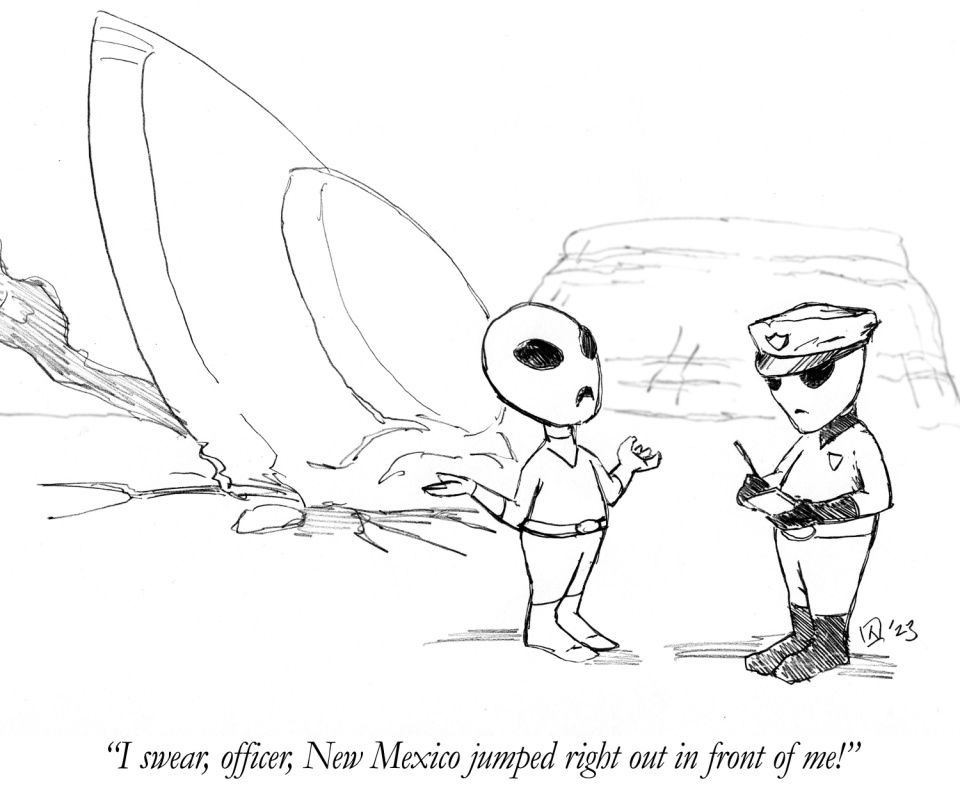

To see how common this behavior is, consider a recent political cartoon by Rick McKee: Facebook Experts. In the caption, a man at a computer calls out to his wife, “That’s odd: my Facebook friends who were constitutional scholars just a month ago are now infectious disease experts.…” No matter what the news brings, we are likely to spin out narratives that end up reinforcing whatever we already believed, and we’re all so sure that our theories and rationalizations are unshakably correct. How many of your friends know for a fact that the Covid-19 virus is only as dangerous as a common flu? How many of them are completely confident that anyone who is worried about the economic repercussions is blithely happy for old people to die so that they can get a haircut? These are the kind of convenient beliefs backed by presumptuous certainty that I’m talking about. We’re drowning in them.

Although these two tendencies—to believe what makes us feel good and to fabricate certainty around those beliefs—are universal, the United States in particular (and the West in general) is particularly susceptible to them here and now due to the retreat of religion (which had a fairly sophisticated approach to mitigating them, as I outlined previously) and the corresponding growth of secularism (which, aside from the narrow case of scientific inquiry and a few Internet subcultures, does not). This is the environment in which ideas are presently competing with each other for adherents.

Now, simple ideas with broad applicability have an advantage over-complicated ideas with narrow applicability. This is because you can get more bang (the applicability) for less buck (the complexity). But there are only so many truly simple and widely applicable ideas. If you care about truth—if you want your ideas to conform to reality—then in order to make them more broadly applicable, you often have to make them more complicated. In most fields, adding new knowledge is all about adding new layers of refinement to address special cases and exceptions. These extensions and elaborations sacrifice simplicity for broader applicability.

For most of us, the rules we live by follow the same general pattern. When we’re young things seem clear and obvious and we judge quickly and without a second thought. As we grow older—as we struggle and fail and try to support spouses and friends and children who all have their own struggles—we learn to temper our judgments and suspend our criticism. This isn’t about abandoning objective truth or perfect ideals. It’s the opposite. Only those who sincerely strive to conform to ideals and only those who subject themselves to objective assessments truly appreciate their own limitations. This appreciation makes us a little slower to judge, a little more gentle, and it inclines us towards beliefs that are more nuanced, moderate, and open. This results in beliefs that still point towards perfect ideals, but with the wisdom of appreciating how long and hard the struggle is to approach them.

But if you don’t care very much about truth, then you can bypass the simplicity/applicability tradeoff. That’s the situation we find ourselves in today. Because the eternal propensity to adopt convenient beliefs is stronger than ever, simple ideas with broad applicability have even more of an advantage than they ordinarily would.

Simple ideas that apply all the time would ordinarily be dismissed because the applications are not valid. It’s not reasonable to believe that the majority of Democrats are literally dedicated to destroying the country, for example. They live here. It’s not reasonable to believe that the majority of Republicans are literally dedicated to the subjugation of women, as another example. Plenty of those Republicans are women.

These simplistic ideas explain a lot with very little complexity, but they do so at the lack of even a minimal level of credibility. In saner times, that would be a dealbreaker. Today? Not so much.

Instrumental beliefs—that is, beliefs chosen for what they can get us rather than for whether or not they are true—tend to be absolutist. That is, as above, they bypass qualified positions like, “some Republicans favor policies that may adversely affect women” or “some Democrats seem to emphasize more the mistakes of our shared history” and go straight to caricatures like “all Republicans hate women” or “all Democrats hate America.”

I don’t believe that anybody sits down and consciously decides to pick self-flattering beliefs without regard for truth.

That absolutism, in turn, renders instrumental beliefs brittle. Ideas that are responsive to truth tend to have a kludgy, patched-together feel. That’s because they have already failed many times in the past, then either been patched up to apply to the new cases or simply cordoned off to only work in some scenarios but not in others. If you have one of these beliefs and you run into a new situation where the belief doesn’t apply, you might be disappointed and frustrated, but you’re not going to view it as a catastrophe. You know the current iteration of your belief has broken down in the past and subsequently been patched up and rehabilitated. It may be so yet again. For someone who has a cobbled-together, ad hoc belief like this (that is: an ordinary belief), failure of belief is not a viscerally traumatic event.

Not so for the unfortunate possessors of absolutist beliefs. These beliefs are pristine, unblemished, and—at least in theory—universally applicable. They’re not supposed to break. And when they do, the holder of the belief is left with no reason for hope. Even if the belief is resuscitated, it will no longer by the kind of absolute that it used to be. And so, because they are absolutist, instrumental beliefs are also fragile.

The fragility of these beliefs has a huge impact on the behavior of the people who espouse them. Cliques that form around absolutist beliefs necessarily insulate themselves in echo chambers. It’s very hard to believe that all Democrats are seeking to destroy the country or that all Republicans are engaged in a war on women if you know any Democrats or Republicans personally. Just a little exposure to the wrong kind of information (in this case: a reasonable person with the opposite political label) jeopardizes the beliefs, and so information must be carefully controlled.

Now, from the standpoint of the belief, it makes sense that you’d want to control threatening information. If you’re a meme like “all Democrats hate America” or “all Republicans hate women,” then it’s in your interest to shelter the people who hold that idea from any dangerous new contrary evidence. But memes aren’t agents. They lack self-awareness, agency, and intentions. So what induces us—the people who hold these ideas—to blind ourselves in order to protect the ideas?

One thing to remember is why these beliefs are chosen in the first place. I don’t believe that anybody sits down and consciously decides to pick self-flattering beliefs without regard for truth, but it’s easy to see how—all else equal—flattering beliefs tend to be picked more often without any deliberate decision.

Once you shackle your self-image to instrumental beliefs, you become personally invested in protecting those beliefs.

When we do that—consciously or not—we inadvertently strengthen an implicit connection between what we believe and who we are. It’s natural for us to feel as though critiques of positions we have adopted are attacks on us, personally. This natural habit is even stronger for instrumental beliefs that were selected precisely because of what they say about us. We become incredibly averse to information that is critical of our self-flattering beliefs because we view that information as dangerous to us.

Once you shackle your self-image to instrumental beliefs, you become personally invested in protecting those beliefs. Drawing upon a different analogy from biology, instrumental beliefs are also like parasites that hijack your cognitive faculties for their benefit and protection.

There’s another factor at play as well. So far I’ve focused on personally instrumental beliefs. That is beliefs that serve the interests of private individuals. There are other kinds of instrumental beliefs, however, and Steven Pinker describes a whole suite of them in The Blank Slate. According to Pinker, social scientists found it convenient to deny (in practice) the reality of human nature because it served as a useful cudgel to combat racism, sexism, etc. If there are no differences between races and sexes, than there can be no basis for discrimination, either. The problem as Pinker put it, is that those who adopt supposedly scientific beliefs for a political end, get “trapped by their own moralizing.”

Once they staked themselves to the lazy argument that racism, sexism, war, and political inequality were factually incorrect because there is no such thing as human nature (as opposed to being morally despicable regardless of the details of human nature), every discovery about human nature was, by their own reasoning, tantamount to saying that those scourges were not so bad after all. That made it all the more pressing to discredit the heretics making the discoveries. If ordinary standards of scientific argumentation were not doing the trick, other tactics had to be brought in, because a greater good was at stake.

It is worth underscoring the point here: beliefs chosen for reasons other than truth might start off viewing truth with neutral disinterest, but they ultimately end up viewing it with hostility. Once you have given up on appealing to objective truth as the ultimate authority, the only recourse left is an appeal to raw power. Truth will seem at first incidental and then inimical to that pursuit and so it becomes first irrelevant and then inconvenient.

Dividing the world into us-vs-them is a natural way to continue to foster the cozy feelings of a pseudo-Zion.

This may sound grim, so far, but things get much worse when we look a little bit deeper at what ideologically-defined cliques—imitation Zion communities, as I described them previously—do to protect their fragile, absolutist beliefs.

For one thing, they seek to proactively discredit anyone who sees the world differently than they do. Dividing the world into us-vs-them is a natural way to continue to foster the cozy feelings of a pseudo-Zion while also protecting your beliefs from criticism or skepticism. Over time, this combination of absolutism and pre-emptive mockery may easily escalate into dehumanization and even violence.

Not everyone needs to be equally discredited, however. The greatest risk to absolutist, fragile beliefs is not from other absolutist, fragile beliefs that are oppositional. It is from beliefs that are balanced and resilient.

Counterfeit Zions organize themselves into codependent pairs: a left and a right-wing that exist in symbiotic antipathy.

That is why partisans reserve their strongest vitriol for more reasonable versions of their own beliefs. Remarkably, what this says is that for these cliques the preference for the kind of belief (absolute rather than moderate) surpasses the preference for the alignment of that belief (left vs. right). There’s a real sense in which they’d prefer to switch from absolute left to absolute right rather than switch from absolute left to moderate left, which is exactly what takes place in many instances when defections take place.

Far from genuine adversaries, counterfeit Zions organize themselves into codependent pairs: a left and a right-wing that exist in symbiotic antipathy. Partisans depend upon their anti-poles to maintain a constant stream of antagonistic vitriol to justify their mutual animosity and ensure that nobody looks at the real threat: any belief that allows the possibility of escape from the quagmire of mutual antagonism.

These codependent adversaries are reminiscent of Hugh Nibley’s analysis of the Nephites and Lamanites in the closing days of the Book of Mormon.

At the center of ancient American studies today lies that overriding question, “Why did the major civilizations collapse so suddenly, so completely, and so mysteriously?” The answer . . . is that society as a whole suffered a process of polarization into two separate and opposing ways of life . . . The polarizing syndrome is a habit of thought and action that operates at all levels, from family feuds like Lehi’s to the battle of galaxies. It is the pervasive polarization described in the Book of Mormon and sources from other cultures which I wish now to discuss briefly, ever bearing in mind that the Book of Mormon account is addressed to future generations, not to “harrow up their souls,” but to tell them how to get out of the type of dire impasse which it describes.

Nibley points out that the polarity described in the final days of the conflict between the Nephites and the Lamanites is a false polarity. With their words they drew passionate distinctions, but in their actions they colluded together as deadly partners. At every point in their downward spiral they mirrored each other and strengthened each other’s resolve. Each took turns outraging and offending the other.

It is true that a single aggressor is enough to create the necessity of defensive action, but that’s not what is depicted in the closing chapters of the Book of Mormon. Instead of a defender and aggressor, there is simply an endless cycle of revenge that requires constantly escalating commitments from either side—leading to a bloody culmination at Cumorah. In a parody of cooperation, this culmination was jointly arranged. Mormon sends a letter to the Lamanite king, the king agrees, and so they march off to the appointed place at the appointed time to finish together the terrible, awful dance they had begun so long ago. The war had been lost long, long before Mormon arrayed his people for their final battle.

Of course, the United States is nowhere near that point. I pray we never reach it.