It has become increasingly clear to thoughtful observers that over at least the last half-century higher education, particularly in the Western world, has lost not only its intellectual but its moral and spiritual bearings. As a result of this loss, the university as a foundational institution is in serious crisis, perhaps even catastrophically so. David Lyle Jeffrey, a fellow at Baylor University, correctly notes this crisis is intimately related to an overall “atrophy of wisdom as a subject for academic reflection, let alone as one imagined outcome of a good university education.”

D. H Davis, the editor of Educating for Wisdom in the 21st Century, notes it was not that long ago that “it was generally believed that the essential purpose of a university education involved shaping both the moral and intellectual character of students in ways that led them to live and do well over their entire lives.” In many quarters today, however, such a claim is most likely to be met with serious skepticism, if not outright hostility. I believe that at the center of today’s crisis in higher education is a profound confusion regarding what exactly it is that universities are supposed to be doing, a confusion fueled by a lack of any clear and compelling metaphysical or moral vision of what education actually means, what the fundamental purpose of a university is, or what sort of persons we should expect to emerge after extensive immersion in the process of obtaining a university education. The university as a foundational institution is in serious crisis.

Part and parcel of this identity crisis is the fact that the modern (primarily, but not exclusively, secular) university seems to lack not only any coherent grounding for itself and its educational project but also any genuinely ennobling and animating sense of what it means to be a person at all, what the aim of worthy human aspiration ought to be, or what human life—educated or otherwise—is really supposed to be about in the first place. As one thoughtful scholar has observed, the modern university has proven to be eminently capable of teaching students how to go about making money for themselves but seems to be entirely inadequate to the task of providing serious counsel as to what might be worth spending one’s money on.

What is missing, according to MacIntyre, is “any large sense of and concern for inquiry into the relationships between the disciplines and, second, any conception of the disciplines as each contributing to a single shared enterprise, one whose principal aim is neither to benefit the economy nor to advance the careers of its students, but rather to achieve for teachers and students alike a certain kind of shared understanding.” He further argues, “the conception of the university presupposed by and embodied in the institutional forms and activities of contemporary research universities is not just one that has nothing much to do with any particular conception of the universe, but one that suggests strongly that there is no such thing as the university, no whole of which the subject matters studied by the various disciplines are all parts or aspects, but instead just a multifarious set of assorted subject matters.”

Much of our contemporary predicament in higher education stems, then, from the progressive abandonment of those traditional intellectual, moral, and spiritual foundations that once provided the university with both the rationale for its institutional existence and the conceptual framework within which its fundamental purpose could be articulated and coherently defended. The steady erosion of the traditional intellectual and moral foundations of the university over the last century and a half has occurred, not surprisingly, as a direct consequence of the rise to prominence of two powerful ideologies: modernism and postmodernism. These ideologies not only seek to eradicate more traditional—or what might be loosely called “pre-modern”—understandings of the nature and meaning of education but are equally hostilely opposed to one another, at both their most basic conceptual level and at the level of practice.

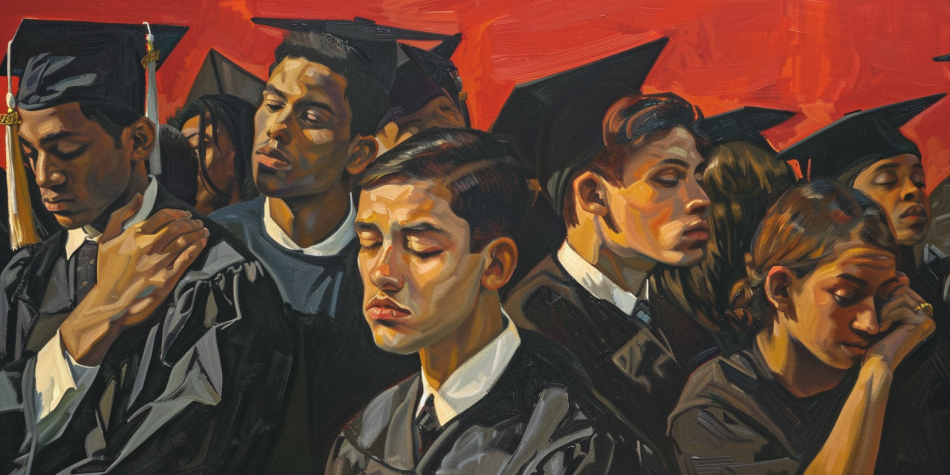

As these two movements have begun to exert a greater and greater influence on thinking in the academy, and subsequently, thinking in the larger cultural and political spheres, much of what were once taken to be the foundational virtues and to constitute the institutional telos of the university have increasingly become the object of open scorn. Prior generations’ understanding of the essence of higher education as a process of “soul-craft,” the formation of virtuous character through the accumulation of knowledge, in concert with the cultivation of wisdom as a result of sustained, disciplined pursuit of “the good, the true, and the beautiful,” has steadily faded as a serious concern of educational or cultural consideration. Ultimately, Davis observes, “Pursuing truth, knowledge, and virtue still sound like perfectly laudable pursuits, but they are not the first things—or even the second things—that define the life of the university.”

What were once taken to be foundational values have become the object of open scorn.

In particular, I will argue that because both the modern and the postmodern approaches conceptualize the purpose of higher education primarily in terms of the pursuit of power rather than the pursuit of truth and, concomitantly, deny the possibility of genuine human freedom, each encourages a nihilistic worldview that, if embraced, ultimately signals the ruin of the university as a meaningful institution. In conclusion, by way of alternative, I will briefly sketch out the broad outlines of a perspective in which higher education is seen to be, first and foremost, and across all disciplines, about the business of seeking truth, becoming good, and attending to the beautiful.

In this endeavor, I will argue that psychology, though currently largely beholden to both modernist and postmodernist thinking and methods, has a significant role to play in defending those richer and more vibrant conceptions of human personhood and freedom necessary for achieving these more worthy (and, indeed, more human) aims of and for higher education in our world today.