The scientistic ideology of modernism held sway over higher education for most of the 20th century and still enjoys enormous influence here in the early part of the 21st century. However, since at least the late 1960s, a rival ideology has been steadily expanding its influence and gaining a surprising degree of educational and cultural popularity. This rival ideology is commonly known as postmodernism. It represents a thorough-going attack on the basic claims and aspirations of Enlightenment modernism, the epistemological authority of science, and the utopian promises of technological progress. Additionally, postmodernism embraces a general attitude of radical skepticism, particularly toward what the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard famously termed “metanarratives” (i.e., science, religion, Western individualism, etc.). Postmodern skepticism manifests as a thorough-going commitment to epistemological, cultural, and moral relativism, as well as a penchant for systemic sociological analyses and critical interpretations.

Rather than a clearly defined system of thought, fixed body of ideas, or unified movement and set of agreed-upon critical methods and techniques, however, postmodernism is perhaps “best understood as a state of mind, a critical, self-referential posture, and style, a different way of seeking and working.” Indeed, a persistent rejection of scientific methodologies, moral understandings, universal truth, and reductive rationalistic explanation is a hallmark of the postmodern response to previously discussed scientistic aspirations of Enlightenment modernism. Postmodernism embraces a general attitude of radical skepticism.

Postmodern thinking emphasizes that epistemological destabilization opens up not only a space for the radical liberation and democratization of all knowledge and truth but also for the free, unbounded play of the imagination in every sphere of life and learning.

While postmodern thought has significantly impacted a wide variety of disciplines and areas of daily life, perhaps no area has been more significantly impacted than higher education. Professor of higher education Harold Bloland notes, “Postmodernism has captured our interest because it involves a stunning critique of modernism, the foundation upon which our thinking and our institutions have rested. Today, modernist values and institutions are increasingly viewed as inadequate, pernicious, and costly.” Bloland further emphasizes that “Because higher education is quintessentially a modern institution, attacks on modernism are attacks on the higher education system as it is now constituted.” Accordingly, then, for the postmodernist, “higher education is so deeply immersed in modernist sensibilities and so dependent on modernist foundations that erosion of our faith in the modernist project calls into question higher education’s legitimacy, its purpose, its activities, it’s very raison d’être.” Bloland’s conclusion is that “postmodernism presents a hostile interpretation of much of what higher education believes it is doing and what it stands for.”

In rejecting the modernist vision of higher education, postmodern thinkers commonly advocate for an activist approach to education, one that seeks not only to destabilize traditional discourses about knowledge, the good, and the true in the scholarly world but to identify such discourses as inherently oppressive and unjust. Therefore, higher education, its foundational institutions, and the larger cultural and political expectations become an active and relentless target of dismissive critique, socio-political resistance, and moralistic contempt. In short, the purpose of higher education is to awaken young minds to the many ways in which they are and have been oppressed by others—by political, economic, and moral systems, by religion, history, and science, and indeed by culture itself—so as to engage in the utopian project of liberationist activism.

At present, this vision of education is most commonly articulated through various formulations of Critical Theory (e.g., Critical Race Theory, Critical Gender Theory, Queer Theory, etc.). It is a vision that has become so pervasive in academia that some commentators have suggested that “a new B.A. model—Bachelors of Advocacy—is emerging in higher education.”

Many identify the emergence of contemporary Critical Theory in the work of the Frankfurt School, a circle of German-Jewish academics who sought to identify and address what they took as chief disorders of society, particularly fascism and capitalism, in the first half of the 20th century. However, closer analysis shows that the origins of Critical Theory extend back to the early part of the 19th century with the rise of the “Young Hegelians” and the curious combination of their ideas with those of positivist philosophers like Auguste Comte (see here for a more detailed treatment of how this combination of seemingly antithetical perspectives came to be). Epistemological destabilization opens up not only a space for the radical liberation.

Because these powerful systemic forces are held to operate outside of subconscious awareness, it is usually asserted that the meaning of social reality as directly experienced cannot be taken at face value. The things of everyday life, no matter how innocent, are never quite what they seem to be. Rather, social and political life is always to be interrogated from the perspective of radical suspicion that Critical Theory fundamentally assumes. Following such a framework, social and institutional life is by its very nature oppressive and, even further, this oppression is inherently nefarious insofar as the primary means by which the oppression is accomplished is through the construction of the subject as fundamentally unaware of his/her oppression—and even, in many cases, unconsciously complicit in that oppression.

For example, a woman who assumes a ‘traditional’ role of stay-at-home mom and who advocates for such a life is to be understood as being oppressed, whether she actually experiences herself as being oppressed or not. Indeed, for critical theorists, the clearest evidence that the woman is being systemically oppressed is the simple fact that she desires a life of traditional motherhood and finds joy and meaning in it. No other evidence or argument is necessary. The woman’s oppression, while obvious to the critical theorist, is entirely hidden from the woman herself by her having “absorbed the patriarchy.” Indeed, she has succumbed to such an extent that she completely identifies with her oppressors and, in so doing, is not only unaware of her enslavement but willingly participates in and perpetuates it.

As the theologian and historian Carl Trueman points out, “In one way or another, modern critical theory focuses on social construction and the manipulative nature of the dominant narratives cultures tell themselves.” Ultimately, only through a process of “consciousness raising,” whereby the “lies and illusions of consciousness” are exposed, does the individual become aware not only of his/her oppression but is also alerted to how they have been endorsing and contributing to that very oppression. In short, only by becoming “woke” can the individual be liberated from the unjust systems and institutions that have hitherto constructed them as an oppressed subject. Therefore, it becomes the role of a just society to educate those who are oppressed to free them from their own ignorance and cultural imprisonment. These powerful systemic forces are held to operate outside of subconscious awareness.

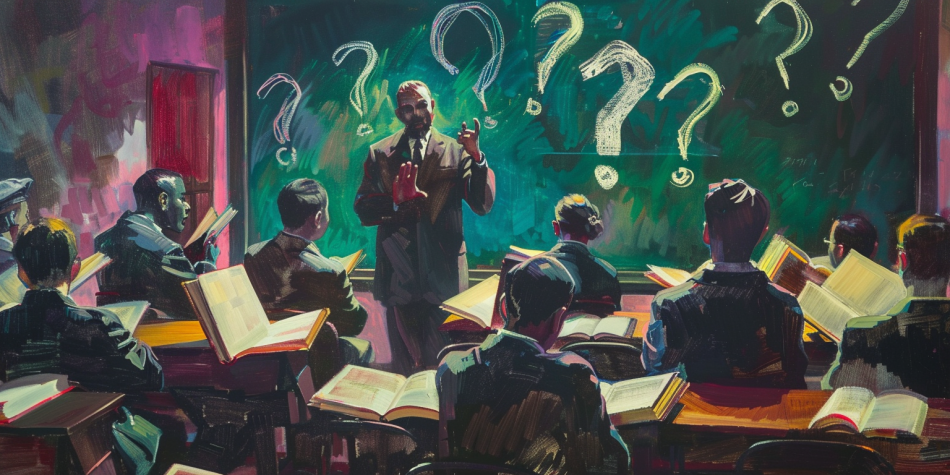

At their core, Trueman argues, the purpose of education from the perspective of secular critical theories is “not merely to expose the world’s ideological captivity, but to effect its transformation.” Indeed, “the remaking of social reality—of the social world—is the aim of consciousness-raising.” Accordingly, the “activist teacher” operates as a “transformative intellectual in her classroom,” someone who can educate students in a way “that combines local knowledge with a critical awareness of the self and an understanding of the larger systems, phenomena, and promises that create societal injustices into a coherent action-oriented framework.” Employing a “critical pedagogy,” the educator as activist and trainer of activists, “eschew[s] traditional education characterized by a hierarchical teacher-student relationship and employ[s] dialogue and praxis in providing oppressed peoples with a tool by which they [can] achieve a critical understanding of their disadvantage and oppression, gain a voice and liberate themselves from the bondage of dominant ideology that [has] served to subjugate and ‘imprison’ them.”

The emancipation from one’s oppression brought about by the consciousness-raising facilitated through instruction in a “pedagogy of the oppressed” involves an exquisite concern for “how power, resources, and opportunities are distributed.” Critical theorists, and other postmodern thinkers, argue that consciousness-raising is “fundamental in the work of moving from a position of powerlessness, internalized oppression, and alienation to one of empowerment and individual and social change.”

Ultimately, consciousness-raising is seen to be the essential first step in a longer, revolutionary process intended to bring about the political action necessary for broad social change to take place via the acquisition of greater personal and communal empowerment. This is perhaps no more clearly evidenced than when Ibram X. Kendi, a leading figure in contemporary postmodern, critical activist thinking, tells us: “I became a college professor to educate away racist ideas, seeing . . . mental change as the principle solution, seeing myself, as educator, as the primary solver . . . [But] I had to forsake the suasionist bred into me, of researching and educating for the sake of changing minds. I had to start researching and educating to change policy.”

For the postmodern activist educator, empowerment—whether personal, social, or political—is ultimately a function of seizing the means of knowledge production. Additionally, the concept of empowerment adopts a basic critical theoretical interpretive lens through which all social, political, and economic life is to be understood as inescapably about power dynamics, oppression, and liberation. Indeed, as Foucault famously argued, power is rooted in knowledge even as power reproduces knowledge to serve its own ends. According to Foucault and other postmodernists, truth and knowledge are, in reality, only functions of power. For example, regarding the nature of truth, Foucault writes:

‘Truth’ is to be understood as a system of ordered procedures for the production, regulation, distribution, circulation, and operations of statements. ‘Truth’ is linked in a circular relation with systems of power which produce and sustain it, and to effects of power which it induces and which extend it. A ‘regime’ of truth.

Similarly, regarding knowledge, Foucault further argues:

We should admit rather that power produces knowledge . . . that power and knowledge directly imply one another; that there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time power relations.

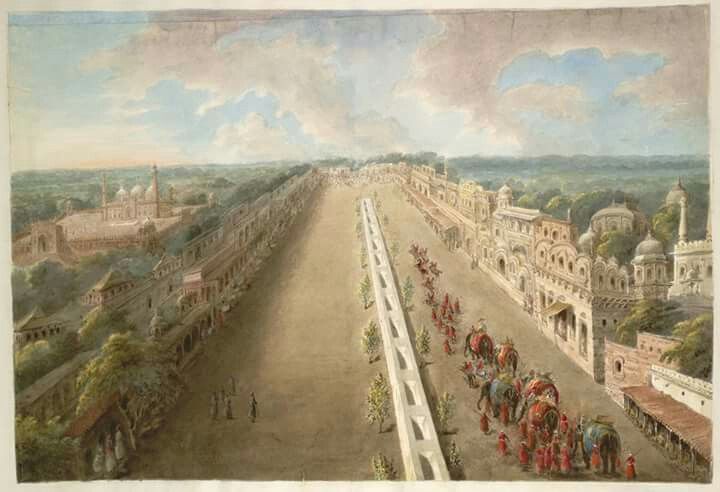

Foucault frequently wrote of what he called the “power-knowledge couplet.” By this term, he sought to identify the ways in which a society validates knowledge through the deployment of power, and vice versa. Thus, he argues that what counts as knowledge is merely ‘societal knowledge’ and is ultimately only a production of those who possess the power to impose their vision and values on others to serve their own ends and maintain their own power and moral authority. It is in this way that the gatekeepers of knowledge—typically taken to be white, European males—subjugate and oppress the powerless, utilizing the very structures of social and moral life that everyone endorses as knowledge. Postmodern thinkers, argue that consciousness-raising is “fundamental.

Indeed, because power constitutes knowledge and knowledge reinforces power relations for the postmodern, critical theorist, every aspect of social life is understood in terms of the relative possession or lack of power. It is in this way that oppression is defined as the lack of power. Oppression is to have no meaningful say in what counts as knowledge, what identities are real and valuable, or what societal arrangements and economic relationships are worth sustaining. It is to have one’s voice silenced and silenced in such a way that one is often not even aware of being silenced at all. Liberation, on the other hand, is necessarily defined as having the power (freedom) to enjoy the political and economic possibilities afforded by the reigning power-knowledge paradigm. The aim of liberation is for one’s personal identity to be affirmed, valued, and protected so that one’s preferred view of the world, social order, and human purpose is validated and granted the political value needed to permit the creation of one’s own moral and social world in whatever form one happens to wish, free from all constraint or limit. Defined almost entirely in the negative, the postmodern utopia of liberation is, Trueman argues, “utopian in the literal sense of urging us to work to create a ‘nowhere,’ a state of fulfillment lacking content.”