Movies, television shows, video games, song lyrics—all have ratings systems. Often raters, reviewers, and consumers refer to content that viewers may want to avoid as “adult,” “mature,” or “for sensitive audiences.”

Let’s stop doing that. Some of the content these labels refer to as “not suitable for children” is not suitable for anyone. In many cases, violence, sexuality, immodesty, profanity, vulgarity, and substance use are added to a movie, show, game, or song with an intention of increasing what the creators might term “entertainment value” or, more likely and unfortunately, market value. In any case, they are almost never “adult” or “mature.”

Whatever you call this stuff, there’s a lot more of it, in games and songs and movies and on TV, than there used to be, due to “ratings creep”—the idea that raters have become more tolerant of inappropriate conduct (see, for instance, this list of movies that were originally rated R and eventually were rated PG-13 or even PG without any editing). Needless to say, this ratings creep hasn’t improved the quality or artistic merit of the majority of creative efforts.

Movies and TV shows provide some of the most obvious examples of what’s gone wrong. The movies that are rated PG-13 (Parents Strongly Cautioned: “some material may be inappropriate for pre-teenagers”) by the Motion Picture Association of America have gotten increasingly violent and contain more profane and vulgar language, and more sexually suggestive content (as well as content that goes beyond suggestion to realistic-looking portrayals of sexual behavior), than they did even a few years ago. With so many movies of all ratings available on streaming services, monitoring family TV and internet use becomes more important than ever. A PG-13 rating simply cannot be taken as an indication that the movie is okay for your 13-year-old (or anyone else) to watch.

The PG-13 rating was created in 1984 and became a “sweet spot”—or sometimes a garbage pile—for movies with surprisingly violent or crude content. (At the time, parents objected vigorously to the PG rating of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, which included a bloody scene showing human sacrifice—but the filmmakers knew an R rating would inhibit their profits and were successful in persuading the MPAA to rate it PG.) The PG-13 rating has since become “one of the most popular and profitable ratings in the film industry,” attracting legions of adolescents and young adults to summer blockbusters and other shows that have edited out content that would get them an R rating in order to land (barely) at PG-13 (and thereby make a lot more money).

What should these creations be called? Not mature or adult.

The Many, Varied Flavors of Movie Violence

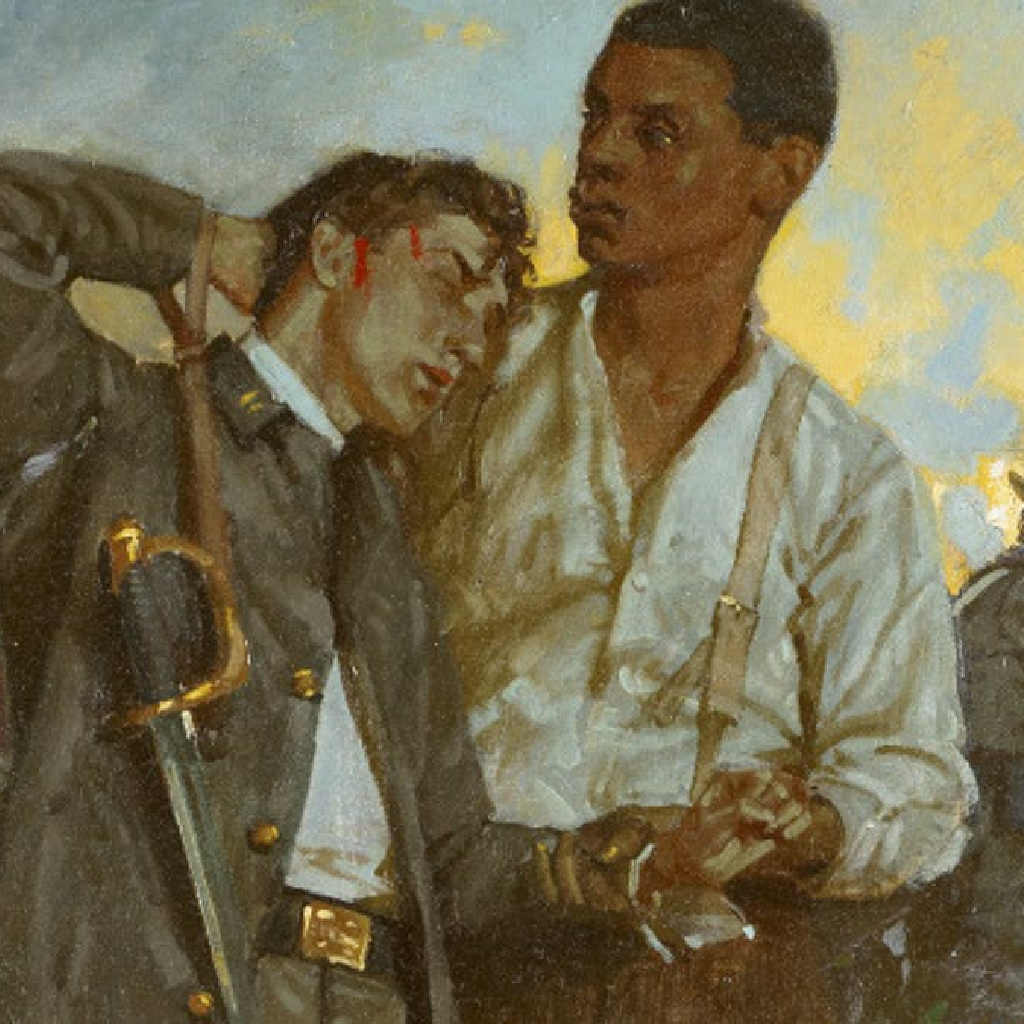

MPAA ratings and others about violence have been parsed into “blood and gore,” “cartoon violence,” “mild violence,” “fantasy violence,” “intense violence,” “realistic violence,” “persistent violence,” “prolonged scenes of intense violence,” and “war violence.” These types of descriptions may be helpful, but let’s not call the content “adult.” Especially when it often portrays a strong person violently harming a vulnerable person. “Cartoon violence” seems especially inappropriate, as cartoons traditionally are aimed at children, and they could be misled when a character is hit with something and the only result is some stars coming out of his head, or when a character is blown up or falls off a cliff (think “Roadrunner” cartoons) and survives, staggering away without more than temporary damage.

Some movie and TV violence, and even shows that include medical procedures, have become so unnecessarily gory and bloody that only a special effects artist could love them—they are hard to watch. Since the actual consequences of violence in terms of prolonged pain and suffering it causes in real life are rarely presented, people of all ages can become increasingly desensitized to others’ pain and suffering—not to mention aggressive, or fearful for their own safety. Let’s not call any of this “mature;” let’s call it what it is: “violent.”

Other behavior that results (or should result) in a stricter rating includes the use of alcohol, tobacco, or drugs.

Alcohol abuse is not only implicated in but a leading cause of much behavior that destroys family relationships, such as abuse and infidelity.

Just A Great Way to Relax

Some TV channels have many advertisements for alcohol, especially (and ironically) channels devoted to sports. Use of alcohol by adults in TV shows is so common as to be almost universally accepted without any warning—adults who have had a bad day reach for or are offered a drink because they “need” it, as though it were not the potentially addictive drug that it is. NYPD Police Commissioner Frank Reagan and the adult members of his family on Blue Bloods always drink wine with dinner, drink beer, and often end the day with a couple of fingers of bourbon. James Bond famously likes his martinis. Portrayals of drinking by adolescents, binge drinking, and drunkenness, often considered comedic, appear even in shows intended for children (think Miss Hannigan in Annie) and in movies intended for adolescents or young adults (think Sixteen Candles).

1962’s (pre-ratings) The Days of Wine and Roses and 1994’s (R-rated) When a Man Loves a Woman are more realistic portrayals of the pitfalls of alcohol use than the drinking-can-be-fun, or funny, messages of more recent movies rated PG-13 or PG. As one commentator notes, “Of all the substances people intoxicate themselves with, alcohol is the least restricted and causes the most harm.” According to Alan J. Hawkins, a professor of family life at Brigham Young University, alcohol abuse is not only implicated in but a leading cause of much behavior that destroys family relationships, such as abuse and infidelity.

Research has shown that children between ages 10 and 14 who watch movies featuring alcohol drinking, and even (what many consider harmless) product placement, are more likely to begin drinking and to binge drink. Although we legally limit alcohol use to people over 21, scenes of joyous, consequence-free alcohol use should not be called “mature” any more than “cartoon violence” is mature.

As to cartoons, almost all animated movies got G ratings in the 1980s and 1990s. The G and PG ratings changed after Shrek (2001) was rated PG for foul language and sexual innuendo. Suddenly the movie studios realized that a PG rating didn’t kill the box office receipts for a movie arguably intended for kids. Now, almost no movies get G ratings, with studios clamoring to get PG ratings for family films, such as The Muppets (2011) and Frozen (2013). “As a result,” one observer notes, “the PG rating for animated and family features is as meaningless as the PG-13 rating is for mass-market tent poles. Just as [2005 superhero flick] Fantastic Four gets the same PG-13 as [violent 2012 James Bond thriller] Skyfall, so too does [2005 animated animal adventure] Madagascar get the same PG rating as Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince [2009, with many very dark scenes of the evil Voldemort’s past].”

Smoking Makes a Cinematic Comeback

Smoking also raises ratings issues in movies. It was seldom seen on TV for a while (TV ads for tobacco products have been banned since 1971) but has returned with vigor, especially on streaming services. Some historical figures, such as Winston Churchill with his cigar in Darkest Hour (2017), would not seem accurately portrayed without their tobacco products. But often, smoking characters are composites who are smoking because, contrary to the facts, “soldiers in World War II all smoked” or “everyone in the 1950s smoked.” (It’s true that cigarettes were donated by the tobacco companies to be included in U.S. GI rations in World War II; but many pushed back, with my own non-smoking father-in-law trading his for something resembling chocolate milk in the Pacific Theatre.) These widely accepted, but not universally true, ideas about how much people used to smoke in the old days have given rise to the interesting MPAA rating description “historical smoking.” Seldom, if ever, does a smoker in a show get told (with that pesky historical and modern accuracy) that he or she smells bad or has stained teeth, or that the high cost of cigarettes is demolishing his budget, or that he has COPD or cancer. The MPAA claims that it labels films that include smoking with an R, but in practice, up to 80 percent of movies with smoking are rated PG or PG-13, and smoking is never mentioned in the ratings specifics. For example, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) was rated PG-13 for “epic battle sequences and some scary images,” but extensive pipe-smoking by Gandalf and the hobbits didn’t elicit a mention. I love that movie and its two sequels, but as much as I want my progeny to be lovers of most things Tolkien, I don’t want them to find the apparently comforting nature of pipe-smoking and the hobbits’ fondness for “Longbottom Leaf” to be memorable or admirable aspects of the trilogy.

In the 1942 classic movie Now, Voyager, Paul Henreid famously lit two cigarettes at a time and gave one to Bette Davis—one moment in a near-constant smoke-fest. An advertisement from the era sought to convince readers that “three days in one” worth of smoking while filming movies would have been easy on Miss Davis’s throat if she only smoked the right brand. Like other problematic content, this smoking was defended then and now as “depicting reality” or “being vitally important to the story” (never mind that both Davis and Henreid were on tobacco companies’ advertising payrolls around the time the movie was filmed).

If we’re going to say that smoking or other conduct is essential to telling an honest story, then perhaps such commercial interests should be revealed for the sake of honesty, too. More important than the honesty-in-portrayal issue, research has linked exposure to smoking in movies with increased adolescent experimentation with and use of tobacco products. While smoking is still often portrayed as glamorous, desirable, and something that adults do (or did back then), let’s don’t describe it as mature.

Making Drug Use a Joke

Use of illicit drugs or prescription drug abuse seems to get consistent ratings warnings, as it should. Thankfully, dramas often depict the downward spiral of behaviors that can result from drug use, including addiction, involvement with crime and violence, or death. (I have read that 1995’s R-rated The Basketball Diaries is sufficiently horrifying to scare anyone away from illegal drugs.) But in comedies, drug use, especially marijuana use, is often portrayed as an adolescent rite of passage and an innocent, harmless pastime, when studies show that, compared to those who don’t use marijuana, those who frequently use large amounts of weed report lower life satisfaction, poorer mental health, poorer physical health, more relationship problems, and less academic and career success (such as a higher likelihood of dropping out of school).

The use of harder drugs and abuse of prescription drugs can clearly have lifelong negative consequences. Let’s not portray drug use, including marijuana use, as the hilarious outcome of harmless activity or a necessary adolescent rite de passage, but as a dangerous failure to exercise self-restraint. No, let’s not call it “mature.”

Profane, Crude, Course, Vulgar

Another source of brain cramp is the profane and vulgar language that is sometimes called “adult language” or even “strong language.” It’s been a few years since my husband and I turned to each other and said, “Can you say that on TV?” because, apparently, you can say almost anything. These poor vocabulary choices used to be avoided as evidence of limited mental prowess or out of respect for those who considered them shocking. I still flinch when I hear the names of God and Jesus Christ thrown around as curse words or just as common exclamations instead of expressions of reverence. Frequent use of crude adjectives assails the ears even as it becomes so commonplace as to lose its value to shock or intensify; it also becomes a distraction. One used to be able to tell the good characters from the bad characters in part because the latter could not control themselves when it came to language choices. Call it foul or coarse or crude or rude or profane or vulgar, but it is neither “strong language” nor “adult language.”

It is, of course, possible to show anger without any of this. For instance, Dickens showed readers the cruelty and harm the ungenerous wealthy can cause to themselves and to the impoverished without having Ebenezer Scrooge cuss out the men who came to him seeking charity for the poor at Christmastime.

Sexuality and the Screen

The portrayal of sexuality is somewhat different because we can choose to forgo entirely lifestyles of violence, drug and alcohol use, smoking, crudity, and irreverence for our own or others’ beliefs. Sexuality, on the other hand, is a part of everyone’s life. Sex is a wonderful part of married adult life—but even so, I don’t want to see it on a screen. Courtship is the basis of many great stories, but when a couple in a romantic comedy fall into bed (or onto any other handy surface) before they’ve had a chance to get to know each other for longer than hours, much less get married, the documented harm that premature sexual behavior does to relationships in real life is overlooked.

I would argue that sexual content and nudity, even worse when combined with violence, are inappropriate for anyone; mature adults do not watch other people have sex or display their bodies onscreen.

Words matter. If the words juvenile and crass and abusive imply detailed judgments, then so should the words adult, mature, and strong.

Of course, many aspects of sexual passion are an important part of real life and real stories. Tolstoy masterfully showed readers the degradation and despair that attend adultery without describing Anna and Count Vronsky in their most private moments. Jane Austen’s novels—and many of the movies based on them—are great portrayals of courtship and sometimes its pitfalls, as when Lydia Bennet falls for the conniving Mr. Wickham in Pride and Prejudice. But the couples we’re supposed to emulate have proper courtships and marry in the presence of family and community before taking off on their honeymoons (“wedding trips,” as Austen might say).

These choices can be complex—Steven Spielberg (who directed the famously parent-disturbing human sacrifice scene in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom that led to the institution of the PG-13 rating) brought us a portrayal of war in all its bloody and unglamorous reality, complete with harrowing violence (and a great deal of cursing), in Saving Private Ryan (1998), one of the best war movies ever and a film that reinforces the importance of doing what is right. An equal or greater achievement is Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993), with its graphic portrayals of the cruelty of the Holocaust, including the sinful pitfalls of evil—but the movie also shows how one person, however flawed, can make a difference in the world. Robert Redford’s Ordinary People (1980), with its excellent portrayals of emotional illness, the importance of getting help when it is needed, and the effects of death and repressed feelings on a family is another excellent film that involves discussion of suicide, parental favoritism, some drinking, and foul language. But all these films—and others of their ilk that do not use the world’s evils as mindless entertainment—were rated R because they are truly for mature audiences; letting children or young teens see them is a bad idea.

Words matter. If the words juvenile and crass and abusive imply detailed judgments, then so should the words adult, mature, and strong. They should not be used as euphemistic stand-ins for portrayals that are violent, profane, vulgar, or illicit as though they were inconsequential or even amusing. Let’s stop calling this stuff adult and mature, and remember what adulthood and maturity really involve.