This is the second essay in a new series exploring important questions raised by the worsening mental health crisis in America—with a focus on different ways to creatively support those seeking to move towards deeper emotional healing. (For part one, see “Hope Sometimes Hurts. Hopelessness Hurts More.”)

Several years ago, I taught a Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction class to teenagers whom we had randomly assigned to take the class or be on a waitlist for later. Following the 8-week mindfulness course, teens consistently showed measurable decreases in both depression and anxiety symptoms compared to those in the control group.

Except for one girl—who had been diligent in doing all the mindfulness practices, but without any apparent relief to her depressive symptoms. In a follow-up interview, the only differentiating factor I could find was that she was on year two of an antidepressant.

One year later, in collaboration with exercise trainer, Jake Asay, we conducted another experiment—this time trying to replicate an international 10-week group exercise program that had been shown to be impactful for people grappling with depression in England (so much so that overseas physicians would often “prescribe” the exercise program to their patients with mild to moderate depression). Once again, we found participants generally experiencing measurable improvements emotionally—including reductions in depression symptoms.

Except for one older woman—who had worked hard to be consistent on all the exercises. Yet despite her diligence, she reported little to no improvement in her depression symptoms.

Why? Once more, the most prominent factor differentiating her from the rest of the group was that she had been on antidepressants for a number of years.

These are, of course, only anecdotes—with more definitive answers dependent on more rigorous research studies, which is precisely the purpose of this essay. I begin here to illustrate why this specific question has been of such interest to me: Are there times when antidepressant treatment that continues for years can get in the way of other opportunities to stimulate deeper emotional healing?

This would be a good place to remind readers that none of what follows constitutes individual medical advice. I write here as a researcher and mental health educator seeking to raise some additional information to inform our larger public discussion about these painful emotional struggles that overwhelm so many wonderful people. And what is right for your own healing is best discerned in consultation with those you trust the most, including family members and good professionals—ultimately following your own deepest intuition and spiritual guidance.

These are deeply sensitive questions that have profound implications for so many lives. I write with great respect and love for the many individuals and families who have spent years, even decades, navigating complicated emotional health questions.

It’s also worth remembering that a wide range of factors can become barriers to emotional healing—including chronic stress, certain physical health conditions, and past trauma. In our mental health conversations, possible inadvertent, iatrogenic effects coming from trusted treatment options are rarely something you hear considered directly and openly.

In the spirit of leaving “no stone unturned” in our widening mental health epidemic, I’m encouraging here some greater attention to this possibility—with all the appropriate sensitivity and care for ways in which antidepressants have been helpful and continue to be helpful to many.

Appreciating short-term benefits without forgetting the longer-term picture. Like you, I have known and spoken with many who have found antidepressants beneficial at different times of their life. For someone grappling with the aching, agonizing emotional burden of depression, any kind of relief can be huge.

That’s why the language in my recent mental health article for the Church of Jesus Christ’s Liahona magazine has been updated to more explicitly mention “qualified medical professionals offering medication” in a list of “additional help from a variety of outside supports” that people may turn to as needed—and why I further acknowledged that “when used appropriately, outside resources can support us as we seek deeper healing.”

It’s true that this kind of shorter-term support can be a help to many as they seek deeper healing. But will these medical interventions lead them to deeper, more sustainable healing?

That’s a very different question—and one I’ve focused much of my career trying to explore. Based on everything I’ve seen and learned, I’m admittedly concerned that we’ve been so focused on the initial relief these therapeutic tools can provide that we’ve paid much less attention to what happens next—after the potent effects of those initial weeks and months shift into something else.

Most of the broader research literature focuses on these same initial effects and shorter-term outcomes (ranging from several weeks to a few months at most). It’s that research that the FDA and other regulatory bodies have leaned upon to reach their conclusions and approve antidepressants and other psychiatric medications.

Although the average length of these controlled studies is about 2 months, clearly patients are taking antidepressants at much longer durations. In a 2018 analysis of federal data conducted by the New York Times, they found:

- Nearly 25 million adults had been on antidepressants for at least two years, a 60 percent increase since 2010.

- Another 15.5 million Americans had been taking antidepressants for at least five years, which had doubled since 2010, and more than tripled since 2000.

In the report, Dr. Mark Olfson, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, said “What you see is the number of long-term users just piling up year after year.”

Given the steep increases in depression and anxiety during the pandemic, there has been a corresponding global spike in usage of antidepressants and other psychiatric medications—no doubt, increasing these long-term trends further. While this may be understandable as an attempt to cope and manage through difficult situations, what do these larger trends mean for people’s emotional healing over time?

In the months ahead, I’ll be releasing a lot more data from my narrative-based sustainable healing research project. But it’s these other larger scale statistical studies that we should pay attention to first. So, what do these more rigorous long-term studies say—especially those examining the outcomes with people on (and off) antidepressant treatment across years?

The available evidence base on that question has received remarkably little attention. Not by doctors. Not by families. And not by patients.

I believe that’s a significant problem. Remarkably enough, this longer-term evidence is not formally taken into account in either our U.S. drug approval process or “best practice” guides created to guide medical practice. Despite previous proposals to make such studies mandatory, no current FDA stipulations require long-term evaluations for any ongoing regularly approval process of psychiatric treatments.

That’s what has motivated my interest in reviewing the available studies looking at “downstream” results—and doing more to bring them to public attention, so that both distressed individuals and the family and professionals supporting them could benefit from what they suggest. It can be discouraging to continue to feel worse, even when you are working hard to be compliant in treatment. These insight below have often been encouraging for people to learn about as they consider next steps in their own journey to deeper emotional healing.

Scientific evidence regarding long-term trajectories of treatment. The list below comprises all the long-term studies of antidepressant outcomes of which I’m aware— specifically, those with rigorous measures of well-being years into antidepressant treatment (I welcome anyone else bringing additional studies to light).

I give credit to award-winning journalist Robert Whitaker for introducing me and so many others to this long-term literature. I have interviewed Bob twice and found him to be a man of great integrity and unusual humility—which is why I believe so many scholars and medical doctors, including at institutions like Harvard and Yale, have welcomed him for academic presentations and grand rounds visits with medical staff.

The remainder of this paper aims to translate this long-term literature for a broader audience. In doing so, many of Whitaker’s own analyses are provided verbatim, with adjustments for brevity—along with summaries of his graphics and statistics. The relevant studies are clustered into two groups: (I) examinations of the long-term trajectory of those staying on antidepressants and (II) investigations more directly comparing those on (and off) antidepressants over the same time span. The studies are listed chronologically in each section, with hyperlinks provided to the original studies so you can read more if you’d like.

I. Long-term trajectory of those staying on antidepressants.

1. 1973 — a 4-6 year follow-up of 94 depressed patients. Van Scheyen, J. (1973). Recurrent vital depression. Psychiatry, Neurologia, Neurochirugia, 76, 93-112.

J.D. Van Scheyen, a Dutch psychiatrist, reviewed follow-up data for nearly 100 patients and concluded based on that and his review of the existing literature that “it was evident, particularly in the female patients, that more systematic long-term antidepressant medication, with or without ECT [electroconvulsive therapy], exerts a paradoxical effect on the recurrent nature of the vital depression. In other words, this therapeutic approach was associated with an increase in recurrent rate and a decrease in cycle duration.”

The researcher also summarized, “more systematic treatment with antidepressants was associated in a relatively large number of patients with an increase rather than a decrease in the rate of recurrence.” While the antidepressants participants took in this study were tricyclic antidepressants (Tryptizol, Tofranil, Noveril)—well-known now to have more side effects, they are still used today, not infrequently.

As Dr. Scheyen notes in the paper, other psychiatrists had observed that antidepressants were causing a “chronification” of the disease. He went on to acknowledge other researchers’ concerns that “continued antidepressant medication” can lead to an increase in emotional volatility and potentially, therefore, cause “a pharmacogenically determined change to a more chronic course.” Dr. Scheyen then asked, “Should [this increase] be regarded as an untoward long-term side effect of treatment with tricyclic antidepressants?”

2. 1992 — an 18-month follow-up comparison of depression symptoms. Shea, M. et al. (1992) Course of depressive symptoms over follow up. Findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Research Program. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49, 782-787.

In this NIMH study which compared four types of treatment (two forms of psychotherapy, an antidepressant, and placebo), the group that was initially treated with the antidepressant had the lowest stay-well rate by the end of the study (19%)—and the highest relapse rate (50%). If study dropouts were included in the analysis, then the results for the antidepressant patients “look even worse … patients receiving the antidepressant were most likely to seek treatment following termination, produced the highest probability of relapse, and exhibited the fewest weeks of reduced or minimal symptoms during the follow-up period.”

3. 1998 — a one-year follow-up of 98 people. Rost, K., Zhang, M., Fortney, J., et al. (1998). Persistent poor outcomes of undetected major depression in primary care: implications for intervention. General Hospital Psychiatry, 20, 12-20.

This study used statewide telephone screening to identify and follow 98 adults with current major depression who made one or more visits to a primary care physician during the previous 6 months. Patients in general practice receiving standard antidepressant treatment (in accordance with practice guidelines for maintenance over time) had higher rates of relapse than those receiving no medical intervention.

4. 1986 — a two-year follow-up of depressed patients. Blackburn, I. M., Eunson, K., & St Bishop, S. (1986). A two-year naturalistic follow-up of depressed patients treated with cognitive therapy, pharmacotherapy, and a combination of both. Journal of Affective Disorders, 10, 67-75.

This research team likewise found that significantly more patients in the group given anti-depressants alone relapsed at both 6-month and 2-year time points when compared to psychotherapy. As they summarize, “There were significantly more relapses at 6 months in the pharmacotherapy group compared to the combined treatment group and the 2 cognitive therapy groups together. The number of individuals who relapsed at some point over the 2 years was significantly higher in the pharmacotherapy group than in either of the cognitive therapy groups.”

5. 2000 – 96 patients followed up to 12 years. Judd, L. (2000). Does incomplete recovery from first lifetime major depressive episode herald a chronic course of illness? American Journal of Psychiatry 1501-4. Two-thirds of all unipolar depressed patients either do not respond to initial treatment with an antidepressant or only partially respond, and these patients fared poorly over the long-term. NIMH-funded investigators reported in this study that “[medical] resolution of major depressive episode with residual subthreshold depressive symptoms, even the first lifetime episode, appears to be the first step of a more severe, relapsing, and chronic future course.”

6. 2004 — a one-year NIMH follow-up of 118 people. Rush, J., (2004). One-year clinical outcomes of depressed public sector outpatients. Biological Psychiatry 56: 46-53.

126 patients originally treated with antidepressants were given emotional and clinical support “specifically designed to maximize clinical outcomes.” 26% responded to antidepressants (defined as a 50% reduction in symptoms), with half of those who responded (13%) staying better for a significant period of time. At the one-year mark, however, only 5-6% of treated patients remained in remission and doing well, which is a much lower remission rate than is typically found in studies of unmedicated depressed patients.

Psychiatrists at Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas who authored the study noted that most clinical studies “cherry-pick” patients most likely to respond well to an antidepressant. In this long-term study of “real-world” patients, the lower percentage of 13% of patients who stayed better for any length of time may be more realistic. These “findings reveal remarkably low response and remission rates,” the lead author John Rush acknowledged.

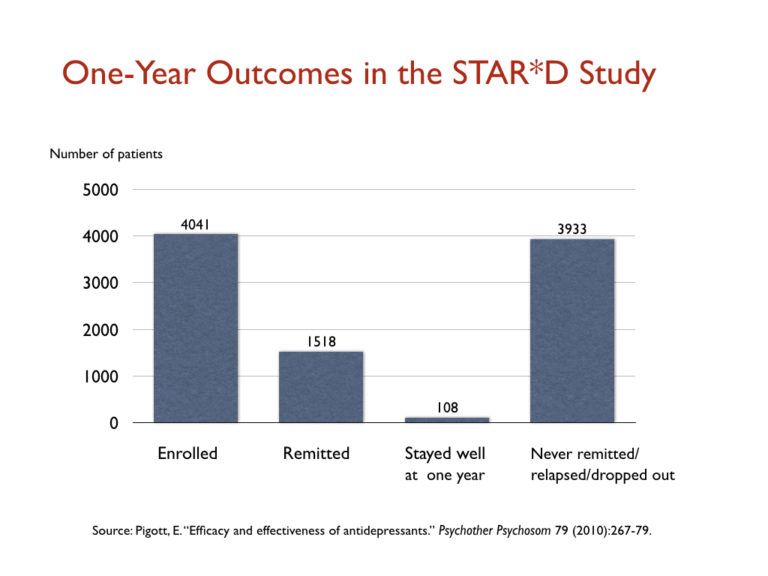

7. 2010 – a one year NIMH follow-up of 4041 people. Pigott, H. 79 (2010) Efficacy and Effectiveness of Antidepressants. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 267-279. In a large NIMH trial of 4,041 “real-world” outpatients, known as the STAR*D study, only 108 patients remitted and stayed well and in the trial during the one-year follow up. This is a stay-well rate of 3%.

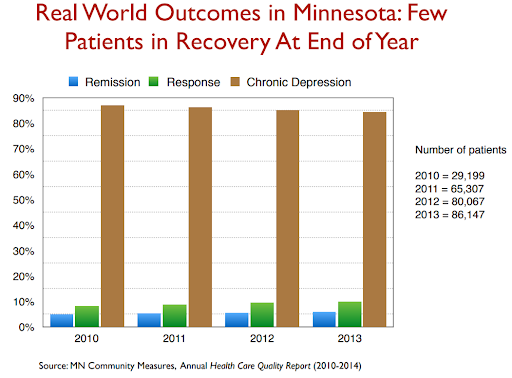

8. 2010 — follow-up of multiple years for over 260,000 patients facing depression. MN Community Measures, 2010 Health Care Quality Report.

This study analyzed all patients in Minnesota treated for depression over time—documenting that over the course of several years, well over 80% of patients remained depressed while being administered long-term medical treatment. Whitaker points out in his talk that this is the opposite of outcome numbers in previous eras, where large majorities of people seeking depression support were finding longer-term healing.

9. 2017 — comparative analysis of outcomes 9 years out. Vittengl, J. R. (2017). Poorer long-term outcomes among persons with major depressive disorder treated with medication. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 86, 302-304.

Jeffrey Vittengl at Truman University conducted a study finding that taking antidepressant medications resulted in more severe depression symptoms after nine years. As Peter Simons summarizes, “Even after controlling for depression severity, participants who took medication had significantly more severe symptoms at the nine-year follow-up than participants who did not. In fact, even people who received no treatment at all did better than those who received medication.”

In addition to collecting information on depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder, the researchers gathered data on other medical conditions, family history of mental health conditions, childhood trauma, personality factors, social support, daily functioning, and alcohol use. While these factors did impact depressive symptoms, Vittengl found they did so equally between the groups. As Simons notes, “That is, initial depression severity does predict lack of improvement—but it does so whether the person is taking medication or not. Therefore, it does not explain how outcomes could be worse with medication.”

10. 2018 — 30-year follow-up of 591 adults in a community sample. Hengartner, M. P., Angst, J., & Rössler, W. (2018). Antidepressant use prospectively relates to a poorer long-term outcome of depression: Results from a prospective community cohort study over 30 years. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 87,181–183.

In this prospective study, researchers from Zurich University of Applied Sciences and the University of Zurich followed 591 Swiss adults from the age of 20-21 until they were 49-50 years old, finding that those who took antidepressants at some point in the study were more likely to have worse depression symptoms after 30 years—even when controlling for initial symptoms and other factors. This finding was independent of illness severity as well as a large number of other potential confounding factors.

As Peter Simons summarizes, “Assessments began in 1979 (baseline assessment) when participants were all 20-21 years old, and assessments were conducted again in 1981, 1986, 1988, 1993, 1999, and finally in 2008 (when they were 49-50 years old). At each assessment, the primary outcome was the severity of depressive symptoms within the previous year. Also, at each assessment, participants reported whether they had been prescribed antidepressants within the previous year. In order to create their predictive model, the authors tested whether being prescribed antidepressants at one assessment (e.g. 1988) increased the likelihood of more severe depressive symptoms at the next time point (e.g. 1993).”

The authors controlled for numerous factors—including gender, education level, marital status, any affective disorder at baseline, suicidality at baseline, family history of depression, subjective distress, childhood adversity, and low parental income. Although each of these factors could be a third variable explaining the results, the researchers found that even taking them into account, antidepressant use was still associated with an 81% increased likelihood of depression severity increase.

The authors (which include Jules Angst, a world leader in mood disorders) write, “These findings are in line with a growing body of evidence from several naturalistic observational studies suggesting that (long-term) antidepressant use may produce a poor long-term outcome in people with depression.”

II. Long-term trajectory of those facing depression who are never treated with antidepressants (compared with those who stay on).

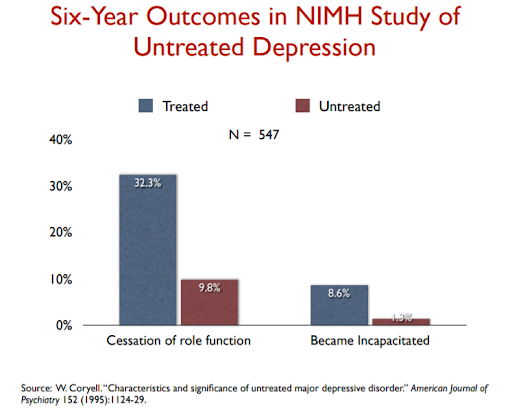

11. 1995 — a six-year NIMH follow-up on 547 people diagnosed with depression. Coryell, W. (1995). Characteristics and significance of untreated major depressive disorder.American Journal of Psychiatry,152, 1124-9.

NIMH-funded investigators led by University of Iowa psychiatrist William Coryell tracked the outcomes of medicated and unmedicated depressed people over a period of six years; those who were “treated” for the illness were three times more likely than the untreated group to suffer a “cessation” of their “principal social role” and nearly seven times more likely to become “incapacitated.” While many of the treated patients saw their economic status markedly decline during the six years, only 17 percent of the unmedicated group saw their incomes drop, and 59 percent saw their incomes rise. The NIMH researchers noted that overall: “The untreated individuals described here had milder and shorter-lived illness [than those who were treated], and, despite the absence of treatment, did not show significant changes in socioeconomic status in the long term.”

12. 1997 — a six-month follow-up of 148 depressed patients. Ronalds, C. Outcome of anxiety and depressive disorders in primary care.British Journal of Psychiatry, 171(1997): 427-33.

In a 1997 study of the outcomes of 148 depressed patients at a large inner-city facility, British scientists reported that ninety-five never-medicated patients saw their symptoms decrease by 62 percent in six months, whereas the fifty-three drug-treated patients experienced only a 33 percent reduction in symptoms. The medicated patients, they noted, most often “continued to have depressive symptoms throughout the six months.”

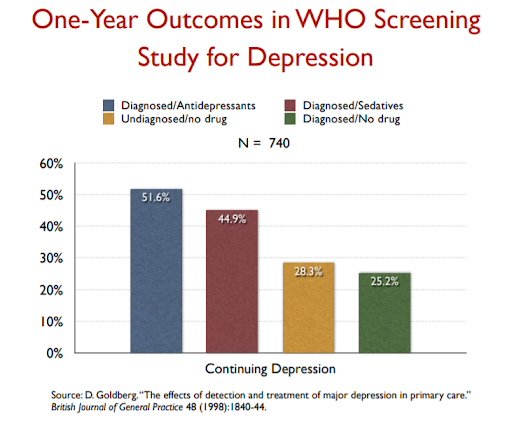

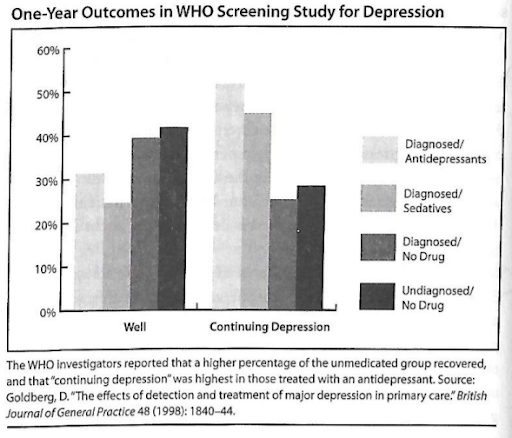

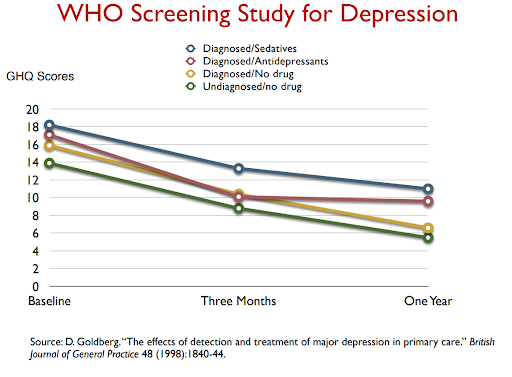

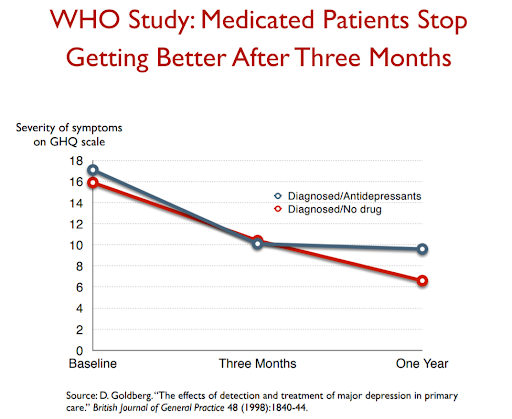

13. 1998 — a twelve-month World Health Organization follow-up on 740 people screened for depression in 15 cities around the world. Goldberg, D., et al. (1998). The effects of detection and treatment of major depression in primary care: A naturalistic study in 15 cities. British Journal of General Practice, 48, 1840-44.

A World Health Organization (WHO) study of depressed patients in 15 cities around the world was designed to assess the merits of screening for the disorder. The study hypothesized that those treated with antidepressants would have the best long-term outcomes, and those whose depression was not detected (and thus didn’t receive treatment) would fare the worst.

Yet the results were the opposite of expected. At the end of one year, the subset of 484 people who didn’t receive psychotropic medications enjoyed much better “general health” and had depressive symptoms that were “much milder.” The non-medicated group was also less likely to still be “mentally ill.” By comparison, the group that suffered most from “continued depression” were the patients receiving ongoing antidepressant treatment.

As the lead WHO researcher summarized: “Patients not given drugs had milder illnesses but did significantly better than those receiving drugs, both in terms of symptoms lost and their diagnostic status.” This was so “even after adjustment for initial scores on each instrument.” The researchers concluded that the “study does not support the view that failure to recognize depression [and get people into treatment] has serious adverse consequences.”

14. 2000 — a ten-year follow-up of 222 people who had suffered a first episode of depression. Weel-Baumgarten, E. (2000). Treatment of depression related to recurrence. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry & Therapeutics, 25, 61-66.

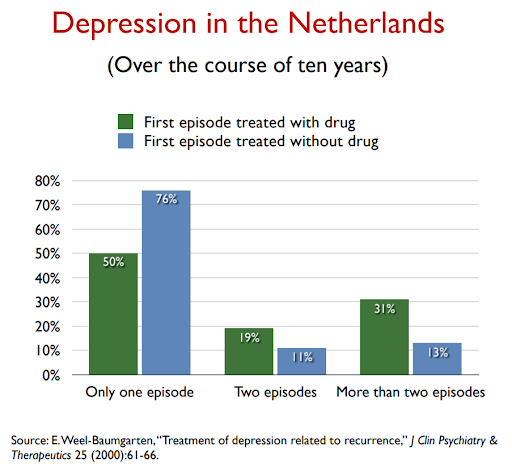

In a retrospective study tracking 10-year case history outcomes, Dutch investigators found that 76% of those not treated with an antidepressant recovered and never relapsed, compared to 50% of those prescribed an antidepressant. The lead researcher wrote, “Even when a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder has been made, spontaneous recovery should be considered for a number of cases in general practice, and watchful waiting could prove worthwhile.”

In Canada, Carolyn Dewa and her colleagues at the Center for Addiction and Mental Health in Ontario set out to explore the relationship between antidepressants and disability rates using administrative data from three major Canadian financial and insurance sector companies. They first identified 1,281 people who went on short-term disability between 1996 and 1998 because they missed ten consecutive workdays due to depression.

Among this group, by examining prescription drug claims, this group learned that the 564 people who opted not to go on antidepressants returned to work, on average, in 77 days—while the medicated group took 105 days to get back on the job, on average. More importantly, those who took an antidepressant were more than twice as likely to transition to long-term disability, with 9 percent of the unmedicated group submitting a request for long-term disability compared with 19 percent of those who took an antidepressant.

In short, “those who did not use antidepressants returned to work sooner than those who did.” Among the possible explanations, the researchers asked, “Does the lack of antidepressant use reflect a resistance to adopting a sick role and consequently a more rapid return to work?” Of course, alternative explanations are also possible—including that more severe cases are more likely to stay on medication longer. Neither hypothesis can be dismissed from the current evidence—with both deserving consideration.

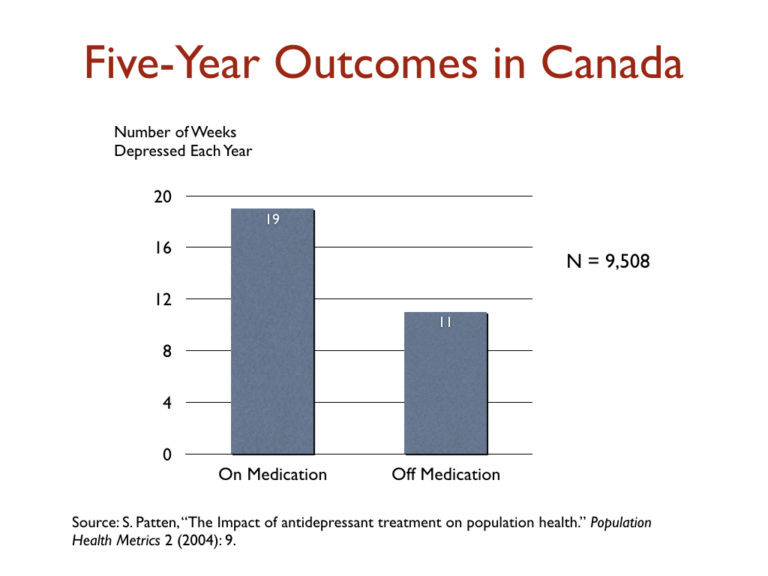

16. 2004 – 5-year study of 9500+ people. Patten, S. (2004). The impact of antidepressant treatment on population health. Population Health Metrics, 9-16. In a five-year study of 9,508 depressed patients in Canada, medicated patients were depressed on average 19 weeks a year, versus 11 weeks for those not taking the drugs. The Canadian investigators concluded that their finds were consistent with Giovanni Fava’s hypothesis that “antidepressant treatment may lead to a deterioration in the long-term course of mood disorders.”

17. 2006 — up to 15-year NIMH follow-up of 84 unmedicated people facing depression. Posternak, M. et al., (2006). The naturalistic course of major depression in the absence of somatic therapy. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194, 324-349.

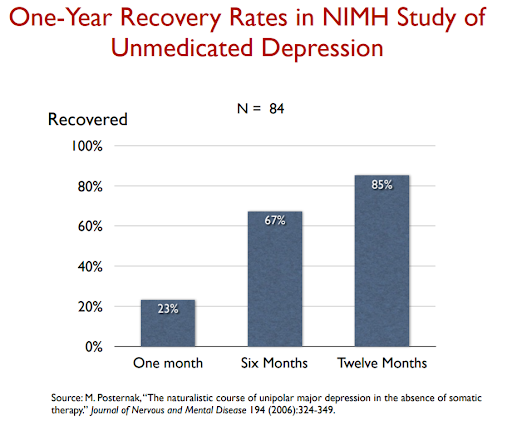

Noting that much of the existing knowledge for poor long-term outcomes in textbooks told the story of medicated depression, Dr. Michael Posternak, a psychiatrist at Brown University, wrote that “unfortunately, we have little direct knowledge regarding the untreated course of major depression.” In an NIMH study of “untreated depression,” Posternak and his team subsequently identified a subset of 84 people in a larger NIMH study who had relapsed back into depression but had chosen not to go back on antidepressants.

How did these 84 people fare over the years they were tracked? Twenty-three percent of the non-medicated patients recovered in one month—and another subset of patients recovered within three months. That number rose to 67% in six months; and 85% within a year. Given these numbers, Posternak and colleagues pointed out that German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin had observed that untreated depressive episodes usually cleared up within six to eight months—adding that their own results provided “perhaps the most methodologically rigorous confirmation of this estimate.”

In sum: most people in this study struck by a bout of major depression naturally recovered. As the study authors concluded, “These results suggest that there is a high rate of recovery in individuals not receiving somatic [medical] treatment of their depressive illness, particularly in the first 3 months of an episode.” In particular, for all 84 subjects who went unmedicated, the “median time to recovery was 13 weeks.”

The research team went on to acknowledge that “treatment-seeking behavior is known to be associated with a worse prognosis” before concluding: “If as many as 85% of depressed individuals who go without somatic [medical] treatments spontaneously recover within one year, it would be extremely difficult for any intervention to demonstrate a superior result to this.”

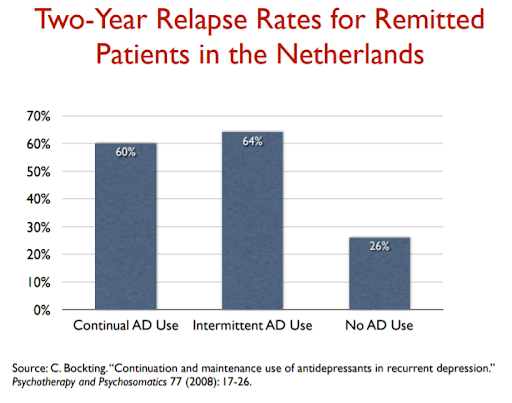

Dutch researchers examined how consistently antidepressants were used in the 2 years prior to a recurrence of depression in a group of 172 individuals. “Despite continuous use” of antidepressants, the group most committed to ongoing treatment relapsed 60.4%. By comparison, those who stopped taking antidepressants after they got feeling better—and who also pursued other preventive interventions—had an 8% relapse rate (the relapse rate was closer to 46% for those who stopped the antidepressant without any distinctively preventive support). That meant a 26% average relapse rate across those stopping antidepressants —which was substantially lower than those who stayed on the medication.

Given the positive short-term effect that many have reported on starting an antidepressant, lead researcher Claudi Bockting wrote, “Continued antidepressant treatment may oppose the initial acute effects of [the] antidepressant.”

19. 2011 — a1-year analysis of 35000 patients. Verdoux, H. (2011). Impact of duration of antidepressant treatment on the risk of a new sequence of antidepressant treatment, Pharmopsychiatry 44, 96-101. French researchers, in a study of 35,000 first-episode patients, found that the longer patients were treated with an antidepressant before withdrawing it, the higher the rate of relapse. Those who were exposed to an antidepressant for longer than six months had more than twice the risk of relapse than those exposed for less than one month.

20. 2017 — 9-year following of nearly 3300 people. Vittengl, J. (2017). Poorer long-term outcomes among persons with major depressive disorder treated with medication, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 86, 302-304. An analysis of the outcomes of 3,294 people who were diagnosed with depression and followed for nine years revealed that those who took antidepressants during that period had more severe symptoms at the end of nine years than those who didn’t take such medication. The difference in outcomes could not be explained by any difference in initial severity of depression.

21. 2019 — 90 patients followed over one year. Hengartner M. (2019). Antidepressant Use During Acute Inpatient Care Is Associated With an Increased Risk of Psychiatric Rehospitalisation Over a 12-Month Follow-Up After Discharge. Frontiers in Psychiatry 10, 79. Swiss investigators, in a study of 90 psychiatric patients discharged from two psychiatric hospitals, found that those treated with an antidepressant while in the hospital were more than three times as likely to be rehospitalized in the following 12 months than those who were not treated with an antidepressant. At the study outset, the antidepressant-user and non-user groups were “matched into pairs” on a variety of clinical outcomes including illness severity, functional deficit, and psychosocial impairment, a design intended to isolate the effects of the antidepressant use.

22. 2019 — 1 year follow-up of 148 people. Amsterdam, J. (2019). Prior antidepressant treatment trials may predict a greater risk of depressive relapse during antidepressant maintenance therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 39, 344-350. A study of 148 people with a bipolar II diagnosis who had recovered from a depressive episode found that the “largest predictor of relapse” over the next 50 weeks was whether they had taken an antidepressant before enrolling in the study. Those who had taken an antidepressant were nearly three times more likely to relapse.

This is the available long-term literature I’m aware of specific to antidepressants—with one exception.

The wisdom of gradual tapering. There is another clustering of long-term literature examining the trajectory of those who try to step away from antidepressants after having been on them for a certain length of time—sometimes comparing those people with others who stay on the medications. I’ve chosen to review this literature separately in a future paper, because of the extra confounding variable of withdrawal effects which makes these studies especially complicated to evaluate.

(Due to higher rates of relapse among those who taper, this literature has sometimes been used as justification for encouraging long-term usage generally. However without adequately accounting for withdrawal effects and the general difficulty of tapering—along with the fact that relapse shows up more frequently in those who take antidepressants for longer periods of time—that broad-brushstroke conclusion is almost certainly overstated and misleading).

As many people know from their experience, the choice to taper off antidepressants can be fraught—especially if people take that step quickly, and without adequate preparation or support. Yet I’ve also interviewed a number of people who taper off antidepressants gradually and safely and find themselves “feeling more like myself” afterwards (an interesting parallel to the initial benefit they felt from the medications).

Whatever other lessons may be taken from this discontinuation research, the most widely-agreed upon takeaway is the indispensable wisdom of careful, gradual, and cautious tapering protocols. Too often, patients are encouraged to titrate off medication quickly—as rapidly as 50% reductions.

This is simply too fast. The three best reviews of the available research on antidepressant discontinuation make this crystal clear. See, for instance:

- Maund, E., et al. (2019). Managing antidepressant discontinuation: A systematic review, The Annals of Family Medicine 17 (1), 52-60.

- Davies, J & Read, J. (2019). A systematic review into the incidence, severity, and duration of antidepressant withdrawal effects: Are guidelines evidence-based? Addictive Behaviors, 97:111-121.

- Horowitz, M.A. & Taylor, D. (2019). Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms The Lancet, 6(6), 538-546.

For those who feel tapering is the right next step in their healing, it is ideal to have professional support in the process. This clearly won’t be the right choice for everyone. For some people, staying in treatment on a long-term basis may be the best option. The important issue is that people have a choice.

For those interested in more education about best practices in the tapering process, check out the Withdrawal Project—a comprehensive online resource created by my colleague and friend Laura Delano (whose own story of long-term healing I wrote about here).

Biological explanations for what’s going on. There are several prevailing biological theories as to why long-term usage of an antidepressant might, in some cases and for some people, trigger a worsening and more chronic course of emotional illness. The most common explanations include the following:

a. Ongoing compensatory changes in the brain. Stephen Hyman, former director of the NIMH, first raised an explanation in 1996, suggesting that the ongoing administration of psychiatric medication prompts a series of compensatory adaptations in the brain in order to maintain “equilibrium in the face of alterations in the environment or changes in the internal milieu.” For instance, ongoing antidepressant treatment has been shown to prompt down-regulation of the synaptic function of forebrain 5-HT2 receptors. (Essentially, in response to extra serotonin being flooded into the brain, it begins to limit its own natural production to avoid excess serotonin levels so that homeostasis and balance can be maintained).

Whatever initial adjustment to brain chemicals may have taken place, remember, the focus here is on the longer-term picture. And just like other things we’re familiar with in the physical world, one sensible step can often trigger other rippling effects we don’t always anticipate. (Think about how widespread use of antibiotics has prompted new adjustments based on unanticipated longer-term effects). For instance, a team led by Dr. El-Mallakh at the University of Louisville found in 2011 that treatment with an SSRI antidepressant leads to a reduced density of receptors for serotonin in the brain. In experiments with animals, such reductions in serotonergic functions were “associated with increased depressive and anxious behaviors.”

Dr. El-Mallakh went on to suggest that over time, antidepressants “may induce processes that are the opposite of what the medication originally produced,” noting that “rather than raise serotonin levels, the drugs over the long-term impaired serotonergic pathways in the brain.” This may “cause a worsening of the illness [and may] continue for a period of time after discontinuation of the medication.”

b. Inducing a more unresponsive biological state. In 2003, Giovanni Fava wrote about these same “compensatory adaptations” and suggested that “a chronic and treatment-resistant depressive state is proposed to occur in individuals exposed to [SSRI antidepressants] for prolonged periods.” He called this condition “tardive dysphoria…due to the delay in the onset of this chronic depressive state,” explaining: “Tardive dysphoria manifests as a chronic dysphoric state that is initially transiently relieved by—but ultimately becomes unresponsive to—antidepressant medication. Serotonergic antidepressants may be of particular importance in the development of tardive dysphoria.”

Giovanni Fava elaborated further in 2011, “When we prolong treatment over 6-9 months, we may recruit processes that oppose the initial acute effects of antidepressant drugs. … We may also propel the illness to a malignant and treatment-unresponsive course that may take the form of resistance or episode acceleration. When drug treatment ends, these processes may be unopposed and yield withdrawal symptoms and increased vulnerability to relapse.”

c. The presence of heightened biological sensitivity. Similar to painkillers leading to a hypersensitivity to pain over the long-term, some have speculated that a comparable hyper-reactivity could be developing with antidepressants as well. As Peter Simons summarizes, “The prevailing theory on why antidepressants might make depression worse is receptor sensitization—the idea that long-term use modifies the ways that neuroreceptors work, causing the medication to become ineffective, and potentially making people vulnerable to worsening depression.”

Larger take-aways. What are we to make of all the foregoing? I conclude with a few final suggestions.

1. Take this possibility seriously. Among this available long-term antidepressant research, this pattern of long-term worsening shows up consistently enough that it’s worth taking seriously. Whatever advantages have been established for short-term antidepressant treatment, statistically speaking, there are some clear risks in my judgment for people taking them long-term.

What kinds of adjustments would this suggest for thoughtful and sensitive usage of antidepressants? These questions certainly deserve more attention and discussion—especially given the fact that our mainstream mental health system relies on these therapeutic tools on an increasingly long-term basis.

2. Multiple interpretations are possible. Of course, some have pointed out that more severe depression may necessitate a longer-term course of treatment by definition—raising this as another explanation for some of these correlations above. That explanation should be considered as well, alongside the distinct possibility that chronic treatment has worsened the long-term course of the illness. This was formally proposed by psychiatrist Giovanni Fava in 1994, when he suggested that the time had come to consider the possibility that “psychotropic drugs actually worsen, at least in some cases, the progression of the illness which they are supposed to treat.” After a decade of more research, he reiterated this by highlighting that a “statistical trend suggested that the longer the drug treatment, the higher the likelihood of relapse.”

To those skeptical of these conclusions, be aware that this pattern of increasing chronicity associated with long-term treatment is not exclusive to antidepressants. Other classes of psychiatric medications show the same patterns. Antianxiety drugs have comparable long-term outcomes. And so do antipsychotics (see this full-text review or this summary of the 25 studies involved).

3. Differentiating short and long-term usage. Broadly speaking, we continue to pay very little attention to the difference between short-term and long-term usage of antidepressants, and that really needs to change.

Based on the available short-term research, it’s understandable why people might be encouraged to consider antidepressants as a part of their initial response to depression. But this is not what people are being told. On numerous occasions, I’ve heard of young and old people being told, “you need to be on this antidepressant for the rest of your life.”

If that’s the kind of advice we are giving, we ought to at least pay attention to what the longer-term research has to say about it. And if we encourage long-term use—insisting this is something they must be on indefinitely (or pretending that it’s not a big deal to stay on for years), we are not only misrepresenting the empirical reality. We are also likely setting people up to be in a difficult emotional spot later. This was evident in the aforementioned New York Times analysis entitled, “Many People Taking Antidepressants Discover They Cannot Quit.”

While there is more to be said about potential side effects in the short term, it’s true that antidepressants can be a short-term relief that can help some as they seek deeper healing. But let’s not mistake them as the source of deeper and more lasting healing—expecting them to deliver more than they’ve been designed to provide.

Check this message against your own experience as well: If you are taking antidepressants or other psychiatric medications long-term, do you feel emotionally well? Do you regularly feel peace and joy in your life? If your loved one is taking them, do you see them experiencing deepening emotional well-being?

Let’s at least allow ourselves to ask these questions and take this conversation seriously. And while we’re doing it, let’s stop pressuring people—especially young people—to go on antidepressants and stay on them forever.

4. Providing support to those ready to taper. Let’s also work to ensure that people feel supported if they feel tapering would be a good option for them. Currently, “there is a wide on-ramp, but it’s often difficult to find the off-ramp,” said Gina Nikkel, former director of the Foundation for Excellence in Mental Health Care. That’s something we can change.

Although it can take time and significant work to taper in a healthy and safe way, and while it’s true can be risks to navigate (which is why this may not be the right choice for everyone), it’s also important to stop seeing the decision to taper off medication as inherently problematic and unwise. As you can see in the evidence above, for some people their long-term emotional well-being may benefit from such a choice.

For further reading:

For those who want to go deeper on this long-term evidence, I recommend:

- Robert Whitaker’s own review of this same material in this chapter of his book and other helpful presentations are available online (see, for instance, this excerpt).

- Dr. Giovanni Fava (2003). Can long-term treatment with antidepressant drugs worsen the clinical course of depression? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 123-133.

- This earlier 2011 review article I did with Florida State professor Jeffrey Lacasse: What Does It Mean for an Intervention to ‘Work’? Making Sense of Conflicting Treatment Outcomes for Youth Facing Emotional Problems. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 92(3), 301-308.

- And other public writing about depression I’ve published in recent years: Towards a Less Depressing Story about Depression; If More Treatment Is the Answer, Why Haven’t the Numbers Gone Down?; Is It Time for a Paradigm Shift in Mental Health?; Is There No Balm in Gilead?: For Faithful Saints Struggling with Depression; Letter to a Desperately Depressed Human Being; To Depressed, Anxious Saints Everywhere