I was disappointed to learn recently that “gaslighting” is Merriam-Webster’s word of the year for 2022.

For those unfamiliar, the term derives from a play (and later, movie) in which a woman notices that the old mansion’s gas lights occasionally flicker. She tells her husband, but he writes off her concerns as delusional, leading her to question her sanity. The movie goes on like this until suddenly it is revealed that her husband was playing with the gas line all along—with the precise intent to make her question her grasp on reality. The term has shifted in meaning to include much more–perhaps most especially some kind of a denial of one’s experience.

Friend: Did you know that “gaslighting” is the word of the year?

Me: No, I didn’t. That’s dumb. I hate that word.

F: Oh, have I told you my favorite gaslighting joke? You’ll love it.

M: No!

F: Yes I have.— Benjamin Pacini (@benjaminpacini) November 29, 2022

The term can be overused, of course. And I do worry about the linguistic creep. But I’d like to vote that we bracket that particular culture war for now. I’ve occasionally had reason to question my sanity, for one thing (thanks Twitter). But there’s also an important opportunity here, and it’s one we’d best not miss.

Better Than “Not Gaslighting.” We have the bad habit of narrating the negative these days. ‘Don’t do this.’ ‘Don’t do that.’

Don’t be toxic. Don’t gaslight.

I wrote recently on the topic of toxic masculinity. My point, basically, is that we spend a lot of time pointing to the “stop being toxic!” poster instead of narrating the positive. Let’s do a thought experiment: can you think of someone acting in a toxic way lately? Now, can you think of someone who you would point out as a good example of masculinity? I’d bet the positive examples are harder to find than the negative ones.

Same goes for truth-telling.

Do we really think the best we can aim for is “not-toxic?” Or “not-gaslighting?”

The deck is stacked against us. We’ve got to contend against negativity bias in ourselves and negativity in the media too. If it bleeds, it leads, indeed.

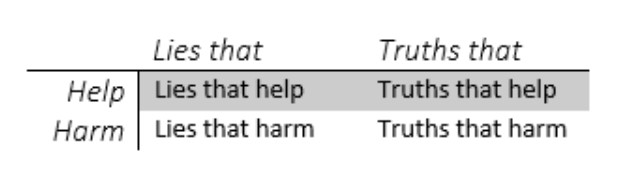

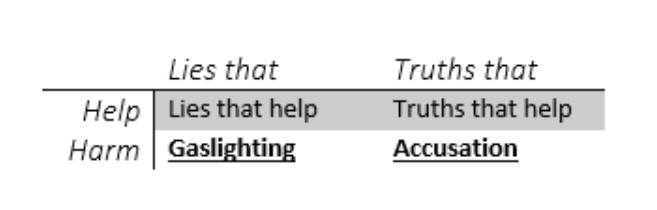

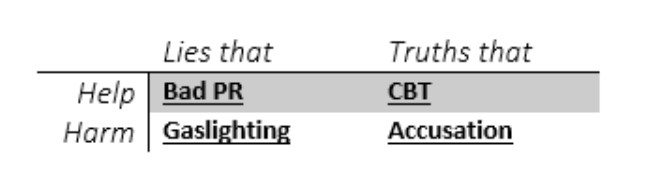

So, let me try to do the opposite. What would the inverse of gaslighting be? Let me offer a working definition—it’s not perfect, but it’s useful. Let’s put gaslighting down as “dishonesty that is intended to harm.” There are two dimensions here, and that gives me a chance to use a neat little 2×2 table, and I’m a sucker for such things, so here’s my beautiful little 2×2 table.

Now, we’ve already said that gaslighting is an example of the “lies that harm” quadrant of the little box, so we can change that out.

What other examples are there in the family of lies-that-harm? I think of libel, calumny, gossip, and others. The key difference between these close cousins is that gossip, libel, and calumny all target a person’s reputational standing while gaslighting is meant to torture the person herself. It’s a particularly nasty kind of harm-by-falsehood, so I don’t think it’s wrong to let her lead the dodgy group.

What would the other categories be labeled? When I think of “truths-that-harm,” prosecutors come to mind. It’s not all bad, of course: we need a stalwart group of litigants who point fingers at the bad guys.

But I’m reminded of something my friend Dan Ellsworth recently taught me: in restorationist scripture, Lucifer is always “the accuser,” while his foil is always “Counselor” or “Advocate with The Father.” In a legal sense, Satan is the prosecutor, while Jesus is the defense attorney. There is no doubt that we need some amount of justice, of course, but there’s a difference between accusation done to reform, to restore, or to ensure justice and accusation that is simply an outgrowth of cynicism and rage—what Dan calls “the epistemology of hell.”

This is accusation: is the domain of certain journalists, leakers, and prosecutors—whose goal isn’t some abstract societal welfare at all. Their motivation is just to score a hit on their personal target. They aren’t standing up for truth; they just want to weaponize true things for their private selfish ends.

If you’d like to see this in real life, say something obviously true on Twitter.

Then wait a while.

Now, what of lies intended to help? Recently, China stopped reporting Covid numbers. I can understand why. Their numbers weren’t reliable, to begin with; they only served to embarrass the regime. Put bluntly, the numbers were lies. More specifically, they were lies intended to protect a reputation, an organization, or some “greater good.” This is the domain of unethical public relations.

There’s a variant here that is worth mentioning: “lies that feel good.” This is what every bad therapist does, what every coddling mother, every unethical PR publicist, and every C-suite yes-man does too.

A patient comes to the doctor and says, “I am depressed! Cure me! Pleasant fictions, hurry!” The doctor wisely replies, “We will administer a double dose of unpleasant realities!”

Let’s call these “bad PR,” but if you want to go with “the fantasies that enable our worst delusions,” that probably works fine too.

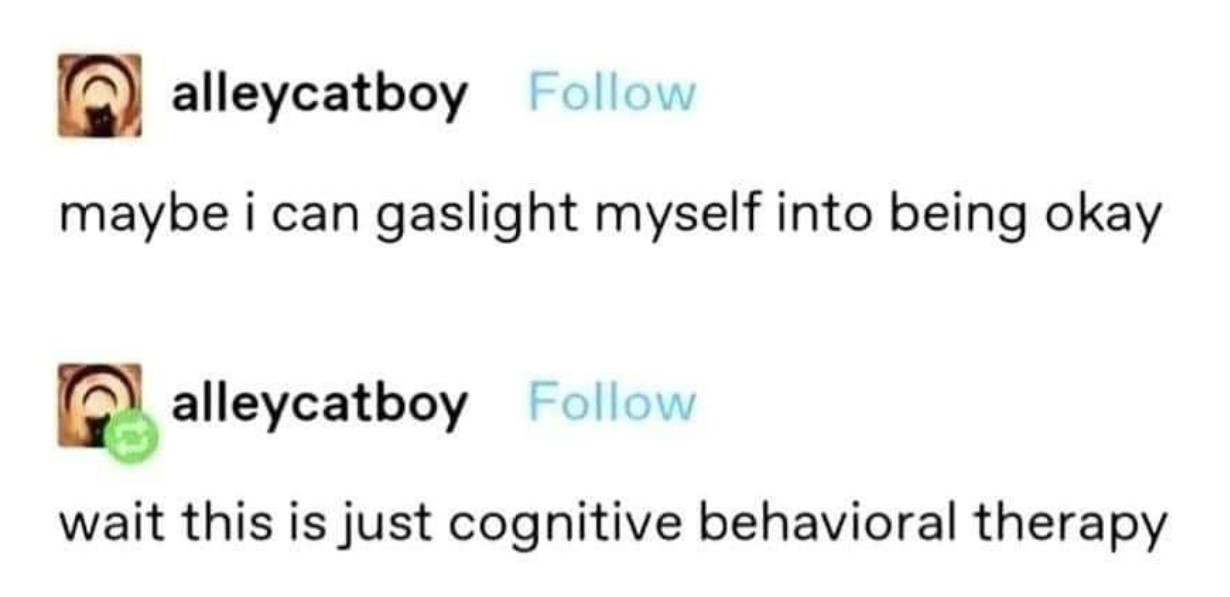

Now we get to the prize: truth that is meant to help. Let’s call it CBT.

Perhaps another gaslighting joke will explain:

The hilarity of the joke is that CBT is when you interrogate what you believe. It’s literally truth meant to help. It’s a way to not believe yourself—and sometimes that is precisely the healthiest possible path.

We need societal CBT. We need to put our thoughts on trial and have methods for prosecuting them, rationally and deliberately and with the intent to help and not harm.

That’s what journalists once did.

There were others. Some politicians were brave enough, once. Religions might argue about metaphysics, but their real domain was moral truth-telling: indicting the conscience of the parishioners, if never without compassion. Their goal was to build better disciples.

Doctors would tell it to you plain–though bedside manner was crucial; therapists would aim for “accurate-and-also-kind” rather than “preserve-relationship-at-all-costs.” School teachers and academics both felt that their obligation was to kindly shoot down bad ideas, not propagate trendy ones.

Ode to the Absent Truthtellers. I’m not mad at therapists, nor at journalists, or at prosecutors. I want to be very clear about that. Rather, I am frustrated by a double-sin on the part of some of them, though.

And frankly, all of us.

I’ll take journalists for a moment. They’re happy to engage in “enabling delusions” for their own side and “accusations” on the other. It’s not about truth anymore. It’s what Twitter personality Gurwinder calls “post-journalism.”

27. Postjournalism:

The press lost its monopoly on news when the internet democratized info. To save its business model, it pivoted from journalism into tribalism. The new role of the press is not to inform its readers but to confirm what they already believe.— Gurwinder (@G_S_Bhogal) November 25, 2022

The same is true of therapists who say nice things to their clients rather than push them to confront their problems. I think, here, of a quote I recently read (but cannot find) about Jung: that where everyone else was whispering pleasantries and fantasies, he took his clients by the neck and plunged them directly into their depression—forcing them to confront it.

Here’s the double-sin: I don’t like the negativity, I don’t like the accusation, and I don’t like the unethical PR and the anesthetic delusions. But the grand tragedy is that journalism no longer lives up to its courageous heritage of truth-telling. Yes, the bad, but also the lack-of-good.

Similarly, it bothers me when I hear politicians engage in populist red-meatery, but in addition to the lies, there’s also the minor detail of the lack of truth. In the same way, it bothers me when I hear therapists say pleasant falsehoods—both because lies are bad but also because telling lies prevents the telling of necessary truths.

We live in a land filled with too many lies, yes—too much confusion, too many wacky ideas, too much ideological pornography.

But we also live in a land with too little truth.

Confelicity and Synopsis. On Christmas, I saw this tweet (yes, I’m publicly confessing to being on Twitter on Christmas … the shame). I found it quite tender.

Word of (every) Christmas Day is ‘confelicity’: joy in the happiness of others.

— Susie Dent (@susie_dent) December 25, 2021

Confelicity seems related to “synopsis” to me. Synopsis means to “see together.”

And the best definition of synopsis I can think of is from a Brandon Sanderson novel.

“Skyward” contains a story about a race of aliens called “Diones,” who reproduce by joining together—very literally. They combine. The two cease to be two and become one. When two parents decide that a combination of the two parents would be an ideal future child, they become a new being. First, however, each set of parents joins together tentatively in “draft” form. Two brains, two sets of eyes and ears, but in one body; they begin to become one but can still separate if the pairing is not a good match.

(I do not remember how Sanderson deals with the necessary decline of population that results from each generation halving over time, which suddenly bothers me more than it ought to.)

Now I don’t mean to spoil anything here, but suffice it to say that there are advantages to having two sets of eyes in one being: you can see reality more clearly than your solitary wingmates. Like bifocals, the two together create depth. They can see more than they could if they were alone.

We see more clearly when we see together—so long as those we see with are trying to see what is true.

It’s a stunning depiction of marriage. My wife is like that to me. She reminds me of what is real when I begin to believe my own eccentricities. I think you have friends like that too—those who are dear to you, who keep your feet on the floor. A friend of mine explained that for her, it is her twin sister:

I’m not married, but I have had the same best friend @alisonwestt for two decades. She keeps me sane. I like to joke that she solves all my problems bc she’s half my common sense. I think it works bc she knows me well enough to know in which ways I tend to think irrationally.

— Olivia West (@oliviawest0) November 29, 2022

Tying ourselves to another—and to a community—helps us to see what they see. So long as the community is good and decent, we will see clearer and crisper; but if the community is deranged or myopic, then we will see with them. This is the problem with social media: not that it lets us raise our voices, but that it swallows up our voices in a sea of tribes.

I had a moment-of-doubting-reality recently, and it was a friend—and one that did not agree with me on the matter at hand, nor one with whom I am particularly close—who spoke up and brought reality back. I wasn’t nuts. I owe that friend. I need a better, catchier word for someone who confirms reality for you like that. Truth-teller will have to do for now.

I hope I can do that for others some time. I think that’s what it means to be a friend.

Consider this thoughtful take:

Reciprocal self disclosure means that you have a group of people who collectively know you in a way you don’t even know yourself—who can see you without your skewed self perception … and you get to be in that support group for someone else. https://t.co/YkQHELb0oc

— Henry Eyring (@HenryEyring) December 1, 2022

I don’t think it’s a minor detail here that the link in the tweet is about how friendship matters.

Action Plan for 2023. I remember reading the research on new year’s resolutions once: most tend to flop. The ones that succeed are not grand hopes or highly disciplined efforts, they’re just changes to a daily routine. Don’t aim to lose 20 pounds. Start the day with a ten-minute walk.

Here are my resolutions, then:

- When I read something that confirms my priors, I will read something that doesn’t.

- I will read (and perhaps subscribe to) something that is thoughtful and deliberate and on the other side of my biases and ideology.

- I’ll do a little better at thanking those who tell me the truth when I don’t like it.

- I’ll vote for at least one person who I think is willing to say true things, even if it is politically costly, independent of their politics.

- I’ll focus on friendship, even with those who disagree. In fact, especially with those who disagree. Seek to see through others’ eyes.

It’s worth a shot. Here’s a toast to 2023–and to the truth-tellers who we so desperately need. May we be willing to hear them occasionally. And may we aim for a goal higher than “not gaslighting.” ”