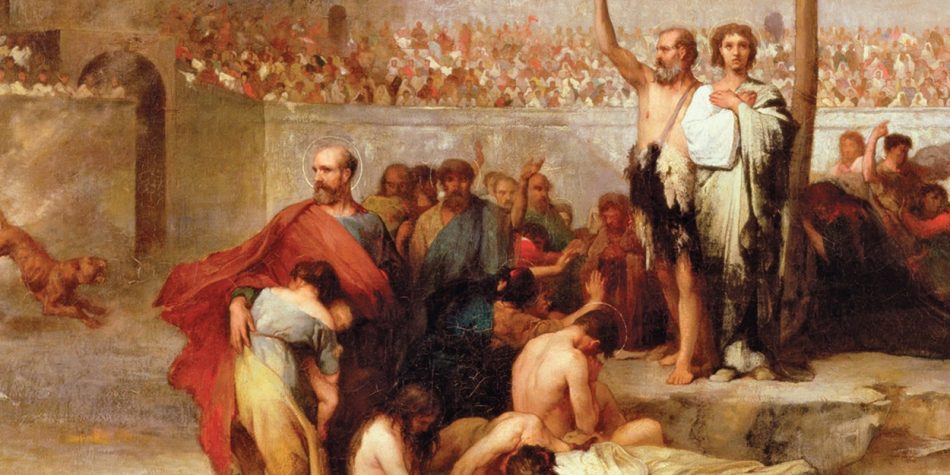

Sir Edward Gibbon, one of the greatest of all historians, who filled his masterpiece The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire with a richness of insight into human behavior that has rarely been equaled, gave considerable thought to the question of why the Roman Empire engaged in periodic persecution of Christians while it tolerated nearly every form of cult, superstition, and religion known throughout its vast empire. This seemed particularly ironic when one considered what he described as “the sanctity of its moral precepts, and the innocent as well as austere lives of the greater number of those who during the first ages embraced the faith of the Gospel” (Vol I, p 444).

He points out that the Christians were something new; not a nation with antique beliefs and traditions which were therefore, in Roman eyes, deserving of at least some respect, but a sect, and a sect that had a higher loyalty than to the nations and the Empire of which it was a part. While one could be a Roman, to take the step of becoming a Christian was to potentially compromise that identity—a compromise that could be fatal. For when the empire was under stress, the state was most inclined to deal harshly with those that did not put its values above all else.

It became possible for Christians to see themselves as Romans and Christians, without compromise

As the Roman Empire gradually came to tolerate, and then embrace, Christianity, it became possible for Christians to see themselves as Romans and Christians, without compromise. As the Christian world eventually converted the various successors of Rome, national identities and Christianity were fused. For a time, if there was to be compromise, it was that of the national identity to the Christian, not vice versa. Change came, of course, as change always comes, sometimes rapidly, often insensibly, but ever inevitably. The Protestant Reformation, the Enlightenment, the growth of the nation state, all vastly modified what came before, yet a distinctly Christian element remained in what we now think of as the Western World (incorporating, as Christianity did from its older parent, the riches of the Judaic tradition).

Both Europe and its various American offspring, the United States, Canada, and Latin America, all retained in one form or another their Christian vision. While chastened by the miseries that developed when church and state were united, the secular nature of the political institutions of nations nonetheless reflected the stamp of Christianity. This is especially true of the United States where “In God we Trust” was the motto of a largely Christian nation. Even when sundered by civil war, as Lincoln noted, each side “read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other.”

While there were deep divides in the acceptance of many groups, be it Catholics due to their relationship to the Pope, or racial groups with different skin colors, or even distinctly different religious traditions, the overwhelming sensibility of the United States (and Europe, Canada and Latin America, too) was Christian. What appeared at the time to have been the triumph of the acceptance of an inclusive vision of a nation that was broadly supported of Christian values may have come with the election of John F. Kennedy in 1960. At that point it seemed that the entire nation had embraced the idea that one could be a Catholic and an American without compromise.

But in the 1960’s another tide began to flow in a different direction. There has been a sharp decline in religious affiliation generally and Christianity specifically. In the United States according to a recent polling, the decline in affiliation is particularly severe among the college-educated and the “elite”—those who set both the cultural trends and the political agenda. In the legal sphere, the concept of separation of church and state and the tension between religious rights and secular standards has been particularly acute. While at times, the overwhelming bipartisan support behind such measures as the Religious Freedom Restoration Act seemed to suggest strong support for providing legal protections for traditional Christian views, that law appears more and more to be a chimera.

In part, this is because of a clever strategy on the part of those pressing the secular agenda. The method, which has had success in both Canada and the U.S., has at least three prongs. The first is to take advantage of the breadth of anti-discrimination laws that have been passed over the last 50 plus years by filling the bodies that administer them with people who interpret them in a way that presses secular, and often anti-Christian, goals. Because the courts have long given deference to the interpretations of laws by administrative agencies and also because the costs of challenging those interpretations via appeal to the courts (such as time, legal fees, and anxiety) make appeals prohibitively expensive and difficult, these agencies gradually but inexorably are able to expand the law well beyond what might have been anticipated at the time of their enactment.

Charges of hypocrisy have a greater impact on religious organizations, whose followers take them seriously, than the secular, where they are sloughed off.

The second method is to have the legislature enact seemingly innocuous, but capacious, laws against unpopular things. Thus, while legislating against “hate speech” in the abstract may not seem problematic for Christians, whose primary obligation is to love God and one another, when authority is delegated to boards and commissions who believe that expressing traditional notions of what is sinful behavior is hateful, the consequences of being called before them can be severe. While on reflection, it might seem peculiar that declaring adultery sinful is not beyond the pale if directed at heterosexuals but is hateful if said of those of the same gender, an unelected bureaucracy has been effectively empowered to render such judgments.

Finally, a more recent technique is to take advantage of the failings of religious institutions and marshal the resources of the state against them in an overwhelming, and often unique, way. Hence the admittedly agonizing failures of the Catholic Church to deal adequately with sexual abuse have been pursued by attorneys general and legislators in a number of states in an unprecedented fashion, cataloging problems going back 50 years (where the bulk of the cases are over a generation old and the alleged offenders are dead), and revoking statutes of limitations long passed. Perhaps this might be understandable if the Catholic Church was a unique bastion of sexual abuse, but similar, and often larger and more recent problems of sexual abuse in schools and other public institutions have received nothing like comparable attention.

It is not all religions that are to suffer as a result of these proscriptions—merely those that cling to beliefs that are contrary to the values of the state.

The implicit message is that a religious institution is uniquely deserving of facing the full wrath of the State, which has an overwhelming ability to undertake litigation on its own. And as if that were not sufficient, the State often authorizes third parties to pursue its goals as well, with the catastrophic consequences to the Church of immense financial liability and the demoralization of its adherents. It is not difficult to understand why the sex abuse issue has become such a point of focus, for it is the perfect vehicle for seeking to discredit the Catholic Church (and others with similar beliefs) when it comes to teachings on human sexuality, for sexual mores in general and abortion in particular, are central to the current secular vision, and charges of hypocrisy have a greater impact on religious organizations, whose followers take them seriously, than the secular, where they are sloughed off.

Efforts to expand these methods are underway, with ever more explicit statements about their intended result. Hillary Clinton remarked at the 2015 Women in the World Summit, “deep-seated cultural codes, religious beliefs and structural biases have to be changed.” Accordingly, additional and enhanced tools are being proposed. Recent Democratic presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke seemed to suggest eliminating tax exemptions for churches that do not subscribe to the currently correct views on same-sex marriage, although he later appeared to limit his position to adoption and other “public services.” One should not forget the famous maxim of Chief Justice John Marshall that “The power to tax involves the power to destroy.”

The crucial distinction that needs to be made is between treating all people with dignity and respect, and compelling agreement with, and acceptance of, values and behaviors that are contrary to their faith.

The high sounding, but deeply troubling, Equality Act has been named a “top priority” for Joe Biden (as it was for several other Democratic Presidential candidates) to further expand existing civil rights laws. It is the details of what will actually result from adding “sexual orientation” and “gender identity” as protected classes under the civil rights laws—such as the potential closure of Catholic hospitals and adoption agencies that refuse to conform—that trouble such groups as the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Like pre-Christian Rome, it is not all religions that are to suffer as a result of these proscriptions—merely those that cling to beliefs that are contrary to the values of the state.

The proponents of these views seem to believe that historical discrimination against and mistreatment of various groups justify ever more sweeping protections. And there is no doubt that many people, such as LGBT+ individuals, over the years have been wrongly treated, even persecuted. This was and remains contrary to the concept of human rights that the Western World is proud to have produced as an outgrowth of its Judeo-Christian heritage. But addressing those problems does not justify swinging the pendulum in the other direction.

The crucial distinction that needs to be made is between treating all people with dignity and respect, and compelling agreement with, and acceptance of, values and behaviors that are contrary to their faith. Religious traditionalists in the Western World have condemned the bombing of abortion clinics as inimical to the culture of life to which they are committed. At the same time, they believe it grievously wrong to be compelled to assist in abortions to keep their jobs in hospitals. Therapists should not be compelled to agree with lifestyles that they believe are contrary to their faith in order to be trained and licensed.

Lest the analogy with the Roman Empire seem overwrought, consider that persecution of Christians was generally more localized than empire-wide. Local magistrates would vary their response from neglect of anti-Christian edicts to the most severe and horrible punishments. So too is the case with interpretations by regional and local authorities. As Jill Harris has pointed out in her book Law & Empire In Late Antiquity, “laws which appear to signal oppression of subjects by the emperor can often more plausibly be read as permission for the subjects to oppress each other” (p.214). Much of the litigation against Christian values is being pursued by determined special interests, seeking to impose secular rules on religious institutions, eliminate historic Christian symbols in all public places, and preventing Christian groups from functioning in schools and on college campuses.

Similarly, quasi-state and non-state institutions, such as colleges and universities are using “diversity statements” to both weed out potential applicants and assess the loyalty of their staff to their current values. What once might have been derided as “loyalty oaths” are now endorsed by their creators as methods to see to it that those who hold what they consider outmoded and unacceptable beliefs are preempted from their institutions.

Private employers are also accelerating the trend. Expressions of belief that are deemed to reflect bias or lack of acceptance may be grounds for discipline or termination.

This checkerboard pattern is what we are seeing today. In the “progressive” enclaves, punitive action against Christians is far more likely than elsewhere, but the trend is accelerating. That is because even in conservative areas, the boards and mechanisms of the state are much more likely to be staffed by those who believe that traditional Christian values are anathema when it comes to cultural matters.

While it is common to assume that the ancient Romans were unsophisticated, if not silly, with their peculiar gods, like Zeus, Apollo or Athena, whose behavior often seemed to mirror humanity at its worst, the Roman elite was hardly so credulous. Roman philosophers, heavily influenced by the Greeks before them, were intelligent, sophisticated, clever and worldly-wise. The elite of the Roman Empire included no shortage of atheists, agnostics, and skeptics. The brilliant tradition of Christian philosophy evidenced first by Origen and brought to its Roman zenith by Augustine, was deeply indebted to Greco-Roman philosophical efforts that preceded it.

As Harris also points out, the use of torture by the Empire when it came to Christians was for the opposite reason that it was used in every other case. The traditional use of torture was to seek a confession, but Christians “were all too ready to confess” their beliefs (p. 126). As Gibbon put it, “The ancient apologists of Christianity have censored, with equal truth and severity, the irregular conduct of their persecutors, who, contrary to every principle of judicial proceeding, admitted the use of torture, in order to obtain, not a confession, but a denial of the crime which was the object of their inquiry” (Vol. I p. 466).

Hence, Christians were tortured to cause them to recant and/or to offer the ritual sacrifices that showed their solidarity with the values of the state. So too, is the rapidly developing state of affairs today, although physical torture has been replaced with subtler means, such as economic loss, inability to pursue a trade or profession, loss of a license and even prison. The baker is not punished for having disrupted a gay wedding, but rather for refusing to design and bake a cake for it and thus affirm the values that the state has legitimated. The doctor is not punished for abusing a patient but rather for refusing to perform a procedure that takes a life but which the state decrees ought to be deemed health care.

The unlawful act is thus akin to the Roman Christian’s failure to offer incense as a sacrifice to the emperor; no one cared whether the Christian actually believed that the emperor was a god in any meaningful theological sense (it is highly unlikely that the Roman elite saw the title in much more than honorific terms), but it was seen as of vital importance in affirming the values that the state believed were important—tradition and loyalty.

In a similar vein, the Emperor Trajan was content with Christians who kept themselves out of the public eye. In a famous letter to Pliny he wrote: “They are not to be hunted out. [Although] any who are accused and convicted should be punished, with the proviso that if a man says he is not a Christian and makes it obvious by his actual conduct—namely, by worshiping our gods—then, however suspect he may have been with regard to the past, he should gain pardon from his repentance.” The contemporary notion is that Christians are entitled to believe whatever they wish to believe, as long as that belief is kept private and does not prevent them from making what is, in the eyes of the government, simply a small gesture of respect for the current gods of the state.

Popular imagination, and understandably, the Christians writing about the persecutions that they or their brethren endured, portray persecuting emperors as bloodthirsty, half- mad monsters. With the likely exception of Nero, historians looking at the broader aspects of their reigns, generally paint these same men as competent soldiers (Decius, Trajan), good to excellent administrators (Diocletian), and even in one case, an exemplary philosopher (Marcus Aurelius). The lesson here is simple. The fact that the motives and intentions of the leaders of the state are not due to mental illness or hideous defects of character, does not mean that their policies are not pernicious.

Generally speaking, the claims against Christians by the Romans were based on a desire to strengthen the body politic for its overall wellbeing, sometimes in the face of existential threats to the Empire, such as barbarian invasion, where unity among the people was deemed essential to preserving the state. That such claims were fundamentally flawed did not keep them from being cloaked in the language of general welfare and concern for the nation and the great majority of its citizens. Today it is claims of serving the greater good of non-discrimination and inclusion that ironically are used to justify the exclusion of, and discrimination against, those unwilling to engage in behavior that violates traditional religious belief or affirming a commitment to values inimical to those beliefs.

The principal reason that Christians were looked on with suspicion by seemingly “good emperors” and their various appointees is that governmental policies and the expectations of public life caused Christians (especially the more pious and devoted) to shun public life. As George C. Brauer Jr. put it in his book on The Age of The Soldier Emperors, Imperial Rome A.D. 244-284:

“What annoyed ordinary Romans most about Christianity was probably its exclusiveness…Rich Christians shied away from political careers which would…oblige them to keep quiet about the gods they hated, and perhaps even require them to torture accused criminals or finance games in which men killed men or beasts killed men…Christian men shunned service in the army, which would train them to fight rather than be peacemakers and force them to march behind legionary standards that the troops adored almost as much as gods” (p.26).

Contemporary efforts to push Christian values out of the public square are likely to have a similar effect, reversing the robust participation of Christian believers in all aspects of public life. Serious Christians will not be interested in serving as judges who must condemn their fellow believers. We are already seeing adoption agencies close rather than place children with same sex couples. Catholic hospitals, doctors, and nurses are on the verge of similar decisions where states are decreeing that certain types of “health care procedures,” especially abortions, are required to be performed by them to remain licensed, avoid penalties, or both.

We must now face is the reality that our society is replacing Judeo-Christian values with a secular, neo-pagan culture.

The trend among Christians to withdraw from public life has already begun. For years we have seen parents choose to homeschool children as public schools have pursued the inculcation of values that traditional Christians find unacceptable. (And now we are seeing secular pushback claiming that socialization of children is better left to the state than parents.) “The Benedict Option” of withdrawal from the secular world into separate communities has generated considerable discussion. Surveys now show that students with traditional values are overwhelmingly unwilling to express them in colleges and universities because of the expected adverse consequences. For Catholics especially, are we to view the election of John Kennedy in 1960 as a high water mark, rather than a new era?

While not every legal case against Christian values has ended in failure, the successes have not been robust. The baker in Masterpiece Cakeshop was not vindicated; rather the court dodged the central question by finding the process tainted by anti-religious animus. Not surprisingly, a new case was pursued. The Little Sisters of the Poor seemingly won in the Supreme Court, yet litigation against their position on required artificial contraceptives continues. Meanwhile, far less publicized cases move forward at the local and state level threatening potential ruin. When embroiled in litigation with the State or determined special interests with nothing to lose, “the process is the punishment.” The cost of defense, the fear of ruinous fines or damages, and the years of anxiety take a huge toll. There is no prospect of victory in these cases—only the potential to stave off an utter defeat.

Surely, one might ask, in a society that has outlawed cruel and unusual punishment, for all this are we really returning so close to reliving Roman history? Are the circuses where believers are fed to the lions likely to return? Consider that today, we have the social media circuses to do psychologically what the wild beasts did physically. Although the most extreme form of persecution by the Romans was the infliction of torture and death, and it therefore remains most vivid in our historical imagination, it is likely that the great majority of Christian persecution was much more familiar: public trial; loss of status and civil rights as a Roman citizen; financial penalties; exile from public service; prison. Some persecutions were aimed largely at the clergy on the theory that eliminating the leadership would bring about compliance by the laity. The purpose of Roman punishment was to humiliate and create fear in order to control behavior; as has been wisely said—the more things change, the more they stay the same.

What we must now face is the reality that our society is replacing Judeo-Christian values with a secular, neo-pagan culture. We are well down this road. If we are to avoid becoming the new Rome of Christian persecution, with less physical pain but every other element of shunning, shaming, and suppressing that society can muster, we must honestly take stock of the current situation. Believers and non-believers alike have a stake in the legacy of the Western World and the freedom of belief and thought that it brought us. It is incumbent on all of us who value that legacy to take a public stand against its subversion in favor of the values of the ever more powerful and unforgiving state.