Do people in our society still believe in sexual morality? At first glance, you might think the answer is no. After all, mainstream outlets like the New York Times describe and celebrate many kinds of sexual practices that would have been taboo in their pages only a short time ago. In “Polyamory Works for Them,” the Times details many kinds of “non-monogamous” relationships, practices, and parties in a tone that might be called “banal transgressive.” Another piece, “We Live in Packs,” sympathetically describes “puppy play,” a subculture in which individuals dress up and act like dogs.

But not so fast! For the Times itself is careful to emphasize certain moral boundaries. The basic moral standard that almost everyone, including the Times, recognizes in intimate relationships is the importance of consent. If someone does not consent, you should not force or pressure them into sex. Period.

Even when many other norms and boundaries are deconstructed or transgressed, consent holds fast. The Times article, “Polyamory Works for Them,” quotes one relationship coach as saying, “Consent is the cornerstone of any well-produced, healthy and fun sex party,” suggesting that even when people have sex with strangers, there are still rules: consent should always be respected.

In a time of so much disagreeable disagreement, it is worth emphasizing common ground when we find it. Virtually everyone agrees that consent should be respected, and this is a good thing. This agreement represents a shared commitment to moral truth, the truth about how we ought to treat other persons. Though some people begin to get nervous when the idea of “moral truth” is brought up, it’s important to recognize that most people (even those who get nervous) already believe in moral truth.

This agreement represents a shared commitment to moral truth, the truth about how we ought to treat other persons.

To say that consent must be respected is to make a claim about what people are owed, a claim that unavoidably implicates notions of moral truth. Though people may disagree profoundly about the content of moral truth, I’d like to suggest that everyone who believes in any degree of moral truth is, in effect, on the same team—a team that is committed to trying to understand and live out the moral truth of how we should treat other people, including (and perhaps especially) in sexual relationships.

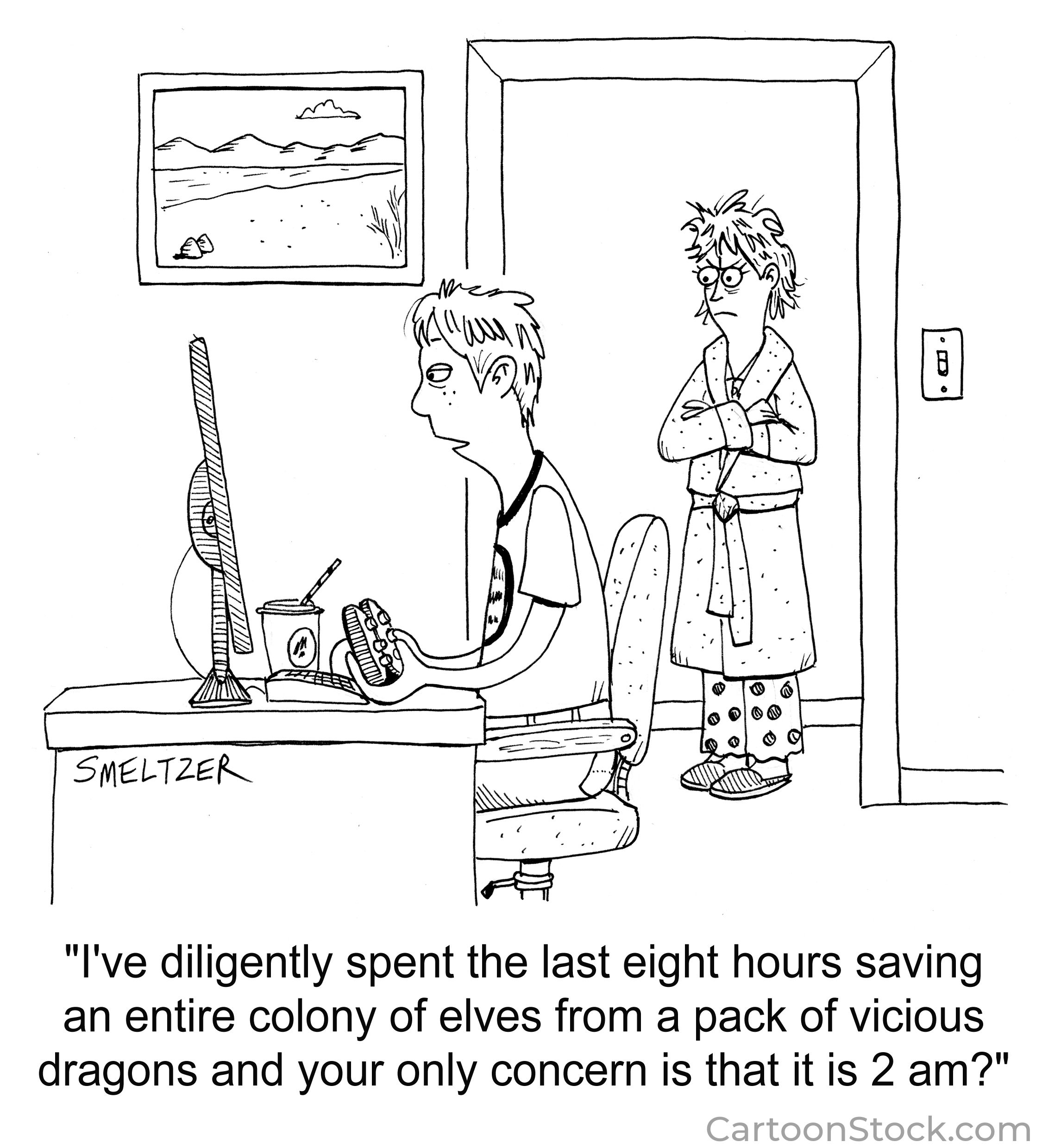

Many people believe that consent is the beginning and the end of sexual morality. In this view, so long as we have secured another’s consent, we can be confident that we have satisfied our moral obligations toward them. The aforementioned Times articles, as well as a good deal of writing about sex today, seem to presuppose this approach. And in college orientations all across the country, consent is driven home as an attempt to resolve the sexual assault epidemic on campus.

But consent, though necessary, is simply not enough. My basic argument is that consent is compatible with many ways of objectifying and depersonalizing other persons (and ourselves) in sex. Saying that consent is the only moral standard opens the door wide to an essentially consumerist approach to sexuality, one in which we can use others as a mere means to the satisfaction of our desires.

Many feminists, for example, have long been concerned with the kind of messages sent by pornographic images, which portray women as objects for male sexual gratification. Even if all parties to the interaction—the women (and men) portrayed in the pornography, as well as the people who produce, distribute, purchase, and consume it—consent at every point (and this is not always the case), the unique and multi-layered identity of a human being (usually a woman) still gets reduced to a one-dimensional image which effectively erodes her personhood.

Far less than a distinctive person of great worth, she becomes a thing to be consumed and discarded. Her individuality is covered over and she becomes fungible flesh for the detached but aroused viewer. Further, consumers of such images treat their own sexuality not as an opportunity to realize a significant connection to another real human being, but rather as an itch to be scratched in the presence of fantasy objects.

Is this way of viewing others morally acceptable? That depends largely on what it means to morally respect people as people. If all that matters is gaining another’s consent, then there is nothing morally amiss with treating other people as objects, so long as they consent to being treated that way. But it is hard to overlook the many ways it is possible to mistreat other people in sexual encounters, even when consent is present. Consent is compatible with contempt, indifference, hostility, or even hatred toward the people one has sex with. It is certainly compatible with exploitation, as we recognize it in other areas of life.

Take employment, for example. Around the beginning of the 20th century, many people claimed that employers and employees should be able to agree to any terms of employment that they wanted, due to an alleged “freedom of contract” found in the Constitution. Other people argued that this freedom of contract allowed powerful employers to exploit vulnerable workers through low wages and dangerous working conditions. Determining exactly which wages and conditions are required as a matter of justice is a tricky business, but the basic idea that it is possible to seriously mistreat someone even when they consent is, I believe, entirely correct. Those who care about living morally should be on guard against these possibilities.

One step . . . beyond consent-based sexual morality is to say that as human beings we ought to care about the well-being of the person we have sex with.

Indeed, even many on the political left recognize that simple consent is not enough, and that some people say “yes” without really meaning it. Hence the added emphasis on “enthusiastic consent” or “enthusiastic agreement,” which are terms that presuppose one ought to care about what their partner is thinking and feeling, beyond verbal willingness to agree to sex.

But though these terms suggest a better way of thinking about sexual morality, they do not escape the same challenges of consent-based sexual ethics highlighted above. With enthusiastic consent, the basic thing one has to verify is that the other person really does want to do this; there is just a higher bar for determining if the person has actually consented.

One step–not the only one, but an important one–beyond consent-based sexual morality is to say that as human beings we ought to care about the well-being of the person we have sex with. This is part of what it means to recognize that person as a person, as a being who has thoughts, feelings, aspirations, and a future that are uniquely his or her own.

Of course, none of this suggests or implies that sex should be pleasureless. It is only to say that whatever pleasure we seek in sexual relationships should be compatible with recognizing the full personhood of other persons. No amount of pleasure experienced by Harvey Weinstein in the course of exploiting many women can compensate for the fact that this pleasure was achieved at the expense of these women.

We ought to care about whether our actions will make this person better off or worse off. We should care about the well-being of the other, not just whether he or she will verbally agree to give us what we want. Though many people object to the idea that sex ought to be paired with love, I think sex (as well as all human action) should be paired with love as defined by noted scholar Cornel West: “Love is a steadfast commitment to the well-being of others.”

Without this commitment, sex can become mere consumption without connection, gratification without mutuality. It can become a solipsistic search for pleasure in which we never really encounter another human person. Indeed, it can become what sex is for many people in the age of Tinder and ubiquitous internet pornography.

There is a robust moral consensus about the importance of consent in sexual relationships. Why not expand our moral thinking to include other ways of treating people appropriately in sex? Why not commit ourselves to treat other people as the complex, multi-layered, intrinsically valuable persons that they are, rather than as objects to be used or exploited?

If we broadened our understandings of sexual morality, we might be surprised to find another person in our sexual interactions, a real person with thoughts and desires and dreams and pains. And in being open to the reality of another person, we might learn something about ourselves: that we are made to be with other people, not simply to use them.