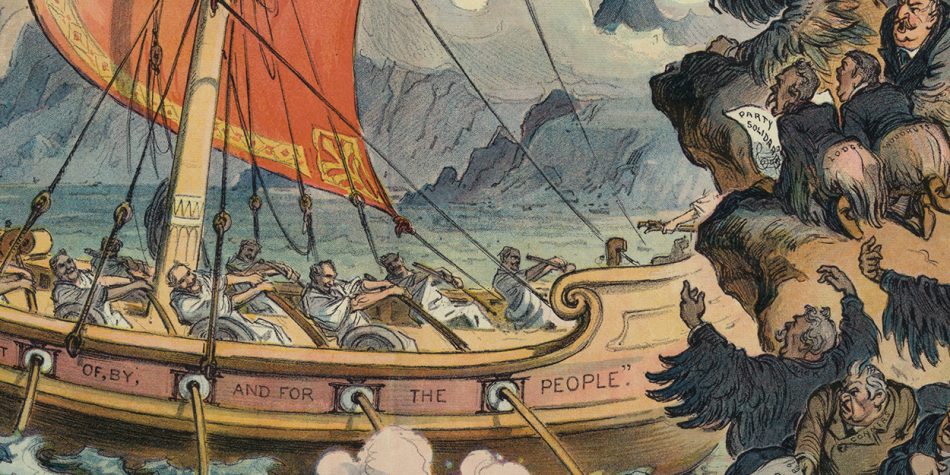

In previous essays, I explored surprising levels of political ignorance in America, while pointing out some surprisingly sensible, rational influences on this lack of knowledge. In this piece, I examine how a lack of political knowledge often translates into a corresponding lack of coherent political ideology—both of which incubate hollow partisanship that carries high interpersonal costs.

Despite the intensity of feeling in the American discourse today, political scientists Donald Kinder and Nathan Kalmoe describe most Americans as “innocent of ideology.” What they mean by that is that however passionate many Americans may be, they don’t necessarily embrace a coherent set of political beliefs. Indeed, according to some survey data, only two to three percent of Americans consider political parties or presidential candidates through the lens of a clear ideology—with approximately 16 percent grasping politics more generally in cohesively ideological terms.

Partisanship is more about group identity than deeply held beliefs.

Instead, it appears that the majority identify as ideological “moderates.” But what does that mean? When variables such as education, political knowledge, and political participation are controlled for, these moderates end up being no different than those “who say they never think of themselves in ideological terms”—with these scholars suggesting, “All things considered, the ‘moderate’ category seems less an ideological destination than a refuge for the [ideologically] innocent and confused.”

“Everyone else—a huge majority of the public,” they go on to claim, “is unable to participate in ideological discussion.” Ultimately, they conclude: “Ideological innocence and widespread ignorance of public affairs go hand in hand. Ideological thinking appears to require a serious investment in public life, an investment few care to make.”

It takes work to decide what you really think. And even more effort to raise those thoughts in conversation with others—especially if they don’t see the world the same way. Despite our ideological mushiness as a people, Kinder and Kalmoe acknowledge the obvious—that almost “all Americans are willing to embrace partisan labels.” Indeed, “from early adulthood to late middle age, Americans tend to be more steadfast in their partisanship than in their ideology.”

Partisanship is more about group identity than deeply held beliefs. Political psychologist Lilliana Mason argues that over the last 50 years or so, political parties have become “more homogeneous in ideology, race, class, geography, and religion,” causing “partisans on both sides [to feel] increasingly connected to the groups that [divide] them.” This means that political partisanship has become associated with other forms of social identity and therefore has itself become an identity largely apart from policy preferences. For example, she writes, “party identity is strongly predicted by racial identity, not racial-policy positions.…The parties have grown so divided by race that simple racial identity, without policy content, is enough to predict party identity.”

In recent decades, religious demographics have also come to predict political identity. By 1992, the religious divide between Democrats and Republicans had, in Mason’s words, “cracked open.” She adds, “the difference between the parties on the percentage of weekly churchgoers had increased to an 11 percentage point gap, with Republicans more churchgoing than Democrats.” By 2012, “parties differed by 14 percentage points in how many attend religious services each week.” Being a churchgoer in America became equated with being a Republican.

Georgetown professor Jason Brennan uses Lord of the Rings language to describe this non-ideological tendency in politics. “Hobbits,” he writes, “are mostly apathetic and ignorant about politics. They lack strong, fixed opinions about most political issues. … In the United States, the typical nonvoter is a hobbit.” Just like their Lord of the Rings equivalents, these members of the electorate care little about events outside of the Shire. Hooligans, on the other hand, “are the rabid sports fans of politics. They have strong and largely fixed worldviews. … Their political opinions form part of their identity, and they are proud to be a member of their political team.” This seems to capture most regular voters and others actively involved in politics.

In so many cases, we have chosen party over family.

Kinder and Kalmoe’s research, however, hints that the situation is even more complex than Brennan lets on: Hobbits and hooligans are often one and the same. Although the more knowledgeable, more politically engaged Americans may be more rabid partisans than less informed, less engaged citizens, this is not limited to the political elite. Even those with limited political knowledge and engagement are increasingly likely to be impassioned partisans—driven less from ideology than visceral, tribal worries.

The work of Stanford’s Shanto Iyengar shows that the more our partisanship becomes entrenched as social identities, the more hostile we become toward opposing party members. In fact, partisan discrimination now surpasses other forms of out-group discrimination, including religious, ethnic, regional, and linguistic. This kind of hostility leads to large numbers of partisans rationalizing harm towards political opponents, with some even endorsing the deaths of opposing party members. As Brennan summarizes, “In general, political participation makes us mean and dumb.”

All of this has very practical consequences. Think about it: We have likely alienated family and friends not because we are standing up for some moral conviction reflected in our political ideologies. Instead, we have chosen political parties as our most important relationship. In so many cases, we have chosen party over family (I mean this quite literally). So while we may feel justified “owning” our “libtard” sister or lambasting our Trump-supporting uncle because he’s a “literal Nazi,” we should pause and consider ways in which our partisan favoritism could be making us a morally worse people.

If political involvement increases our hostility or mistrust toward our fellow countrymen and women, maybe we are doing it wrong.

This is why philosopher Chris Freiman suggests that we steer clear of politics. In a forthcoming book he explains, “Not only do you have reason to doubt that your [political] participation is aimed at good consequences rather than bad ones, you also have reason to doubt that your political activism will have a meaningful impact.” As I have shown before, a single vote means relatively little, statistically speaking. And, as Freiman points out, this is true of other forms of political participation, such as protests. For example, the March for Science attracted over one million participants. “Would the impact of that march have been any different if the total number of marchers had been, let’s say, 1,072,438 instead of 1,072,439?” Freiman asks. What’s more, he says “as partisan politics consumes more of our lives, we become less happy, less trusting, and less understanding of others.”

Many consider active involvement in the political process to be an important part of what it is to be an American. That will always be an important part of citizenship for many of us. While recognizing that, it may be worth asking ourselves: if political involvement increases our hostility or mistrust toward our fellow countrymen and women, maybe we are doing it wrong and wasting our time. Perhaps, then, we are better off redirecting our energies toward more of the good, the true, and the beautiful. We can help the poor. We can get to know our neighbor. We can strengthen family ties. We can mentor a child. All of this is dramatically more substantive and healing than the rancorous partisanship that only divides. Anton Chekhov wrote in a masterful short story about a man with a terminal illness who laments his long life of self-absorption and cruelty: “If there were no hatred and malice, people would be of enormous benefit to each other.”