Other articles in the series include: Do Utahns Struggle With Body Image More Than Others?, Are Religious LGBT Youth in Utah More (or Less) Prone to Suicidality?, Are Utahns More Depressed than Everyone Else?

People love to say things about Utah, don’t they? As a proxy punching bag for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, it’s remarkable how robust and long a life some Tall (and Terrifying) Tales about the state enjoy.

For instance, there’s that story about Utahns being more depressed than everyone else—or LGBT+ identifying youth in the state being more likely to experience suicidal ideation—in each case presumably due to teachings about covenants, sexuality, and identity. Other stories seem to take on added popularity every year—about, for instance, Utah women having a peculiar affinity for plastic surgery (and associated poor body image), and Utah men having an equally singular predilection to pornography (all of which, as the story goes, is made worse by ongoing encouragement towards moral purity and relishing our identity as sons and daughters of a living God).

This week, we’ve decided to commemorate our Scariest Holiday by spending some time diving deeper into each of these Scary Stories, starting with some popular local mythologies about pornography that just don’t seem to die. In none of these forays, of course, are we denying the seriousness of these problems—in Utah and beyond. The first step in knowing what to do about a problem, though, is getting clear on its true scope and nature—trying our best to see “things as they really are.” No one is served by inflated, deformed, and exaggerated accounts of what’s going on—certainly not the people in Utah, and not even those who seem to revel in any added bit of “evidence” that feeds and keeps alive their own dark view of the state’s dominant faith.

I had the good pleasure of knowing personally the nation’s foremost expert in pornography research, Gary Wilson. Drawing on the fruits of his life’s work, we take up in what follows the most popular pillars of the Scary Story (about Sex) some people still love to tell about Utah—highlighting how deeply at odds both elements are with consensus conclusions of the research literature itself. We begin exploring the fashionable hand-wringing over “fear-mongering” and shaming supposedly rampant throughout the state.

Misrepresenting the science of pornography. In a Salt Lake Tribune feature on pornography recently, a young man was interviewed as suggesting the Church had made things “harder for people” by its “harmful teachings about sex”—which he claimed had “really messed with my life.”

What was harmful about teachings this man had grown up being exposed to in the Church of Jesus Christ? Warnings about the addictive nature of pornography itself are highlighted in the article as being potentially damaging. With credit to Tribune reporter Kaitlyn Bancroft for attempting to represent a spectrum of views in her piece, the article relies centrally on one mental health professional, in particular, to represent a more “scientific” position on pornography.

Latter-day Saint clinical psychologist Cameron Staley was quoted as arguing that the label of addiction “isn’t clinical or scientific when applied to a person’s pornography viewing.” Remarkably, Staley claimed that—in contrast with the substance abuse literature—the body did not change in any substantial way from seeing sexual images: “What’s different about viewing sexual images,” he suggested, “is you’re not really ingesting anything in your body that would change neural transmission or how you would metabolize anything.” Of all 57 neuroscience studies done on porn users and sex addicts, all but one provides support for the addiction model.

Hmmm. It’s certainly fair to point out meaningful differences in how people understand the word “addiction”—and to be sensitive about how we use it. Staley and others are not wrong to raise concern with how some can over-identify with addiction in a way that eschews responsibility. And they are equally right to call for more attention to the broad array of life burdens (trauma, grief, isolation, sorrow, anxiety, health problems) that can make someone more drawn to anything to make the pain stop.

All this is wise to consider. But none of them are contradictory on either a conceptual or practical level to the reality of compulsive-addiction patterns where someone’s freedom can become severely limited for a time (at least in a certain area). As the Fortify training emphasizes, even for someone struggling to stay away from pornography, there is a lot they can still choose. Research has confirmed that small and large adjustments in lifestyle can, over time, help grow someone’s sense of control and power to resist and overcome compulsive-addictive patterns. For instance, simple improvements in stress reduction, mindfulness training, deeper spiritual connection, better sleep, and physical activity, can all help grow “willpower” over time.

And the reality is that for many, acknowledging a real limitation in agency is the first step needed to take seriously the needed adjustments of heart, mind, and life, that allow them to finally move out of the morass. That’s what the 12-steps do so well.

The larger consensus of the literature is clear: rather than a seeming contrast with the substance abuse literature, pornography research mirrors it. This is not a controversial statement—not according to these many brain researchers OR to some of the top researchers in the world who authored 32 recent literature reviews & commentaries all of which support the idea that pornography is addictive (Many of these same experts, by the way, have robustly critiqued outlier studies by Dr. Staley and others that claim otherwise).

Why reference this single outlier scholar, while disregarding what the bulk of scholarship is saying? At one point in the article, Staley references the body’s physical tolerance to toxic drugs that can build up and set the stage for painful withdrawal symptoms—arguing that no such physical reactions happen with pornography. Yet once again, there are over 60 studies reporting findings consistent with escalation of porn use (tolerance), and habituation to porn (as you would expect with addiction), as well as at least 15 studies demonstrating clear withdrawal symptoms in porn users.

One of the main takeaways of the Tribune piece is that pornography addiction—if it occurs at all—happens in a “very small number of individuals” and that, even then, the effects of porn are simply not as concerning as religious teaching might suggest (certainly not something to get people frightened about!) And yet once more, the article and its scholarly sources simply disregard overwhelming evidence to the contrary. See for yourself—checking out summaries below of available literature on the stirring scope of porn’s impact on body, heart, and relationships:

- Impact on sexual problems. Over 40 studies link porn use/porn addiction to sexual problems and lower arousal to sexual stimuli. (Gary Wilson points out “the first 7 studies in the list demonstrate causation, as participants eliminated porn use and healed chronic sexual dysfunctions”).

- Impact on relationship satisfaction. Over 80 studies link porn use to less sexual and relationship satisfaction. Wilson notes, “As far as we know all studies involving males have reported more porn use linked to poorer outcomes [with] either sexual or relationship satisfaction. While a few studies report little effect of women’s porn use on women’s sexual and relationship satisfaction, many do report negative effects”—see Porn studies involving female subjects: Negative effects on arousal, sexual satisfaction, and relationships

- Impact on mental health. Over 85 studies link porn use to poorer mental-emotional health and poorer cognitive outcomes.

- Impact on sexist views. Over 40 studies link porn use to “un-egalitarian attitudes” toward women and sexist views.

- Impact on sexual aggression. Over 100 studies link porn use to sexual aggression, coercion, and violence. (But, wait doesn’t porn reduce rape in a country? That popular notion is flatly refuted by the full scope of research, see here).

Some may wonder whether the foregoing patterns are merely correlative. No. Over 90 studies demonstrate compulsive porn use is causing negative symptoms and brain changes.

The bottom line is this: It’s far past time to dispense with this dishonest and damaging notion about porn not being addictive, not impacting the body, not leading to withdrawal effects, and not being harmful to real lives and relationships.

In the same moment, let’s thank heaven there are still some institutions and leaders raising a warning cry— the Church of Jesus Christ among them. (Certainly, we can all do so while better ministering with love to those seeking deeper freedom from the same).

After years of working to support thousands of people in finding deeper freedom from pornography, I can say this: among the most harmful things you can do to someone in the grips of compulsive pornography use is to convince them that the problem isn’t porn—it’s the people concerned about the porn! I’ve watched close-up how people’s healing journeys can be derailed almost entirely by such facile and caustic messages. If critics of Latter-day Saint teachings would like to continue promoting the idea that a conservative sexual culture has backfired on itself, then they will have to confront a less convenient set of data.

A myth that just won’t die. One person’s post in an online forum is reflective of this popular sentiment, “I can’t remember where I heard it, but I think Utah is #1 in online [porn us] as well.”

You’ve likely heard that too—maybe more than once. But is it true?

Not even remotely.

I wondered about the same awhile back, until this same agnostic researcher, Gary Wilson, pointed out how dubious this oft-repeated claim is. With credit to his own analysis from which much of this is adapted and another deep dive from economist Tom Stringham, let’s review below what you need to know about this well-worn trope.

The claim of Utah’s purportedly higher porn use centers around a single study with viral fame. That often-repeated meme arose from Benjamin Edelman’s 2009 economics paper “Red Light States: Who Buys Online Adult Entertainment?”

There’s a lot to be said about this study and its significant complexities (see notes at the bottom), but of even greater interest here is how little critical scrutiny the study has received over the last decade. Instead, as Tom Stringham notes historically:

The Latter-day Saint blogosphere lit up with commentary after the release of the famous original study, and the conclusions of the paper became a focal point of the growing discourse about sexuality among Latter-day Saints online. … After a few months, the Utah porn statistic became entrenched in conventional wisdom. Blogs would make reference to the statistic, and having drawn their conclusions, move on to provide explanations and accusations regarding the phenomenon.

One reason this study achieved such infamy is how well it appears to reinforce the idea that religious people are actually deeply hypocritical—hiding their own sexual obsession right underneath their sermonizing about the sacredness of sex.

That would be quite a story if it were generally true. (It is true, of course, in too many instances). But once again, something very inconvenient is not being acknowledged here: that when we zoom out from this single study, there are 23 other studies that tell the opposite story—namely, that religious people are substantially less likely to use pornography than non-religious folks. That is the conclusion of every single one of these studies hyperlinked below, in order of publication date:

- Adult Social Bonds and Use of Internet Pornography (2004)

- Generation XXX: Pornography Acceptance and Use Among Emerging Adults (2008)

- Internet pornography use in the context of external and internal religiosity (2010)

- “I believe it is wrong but I still do it”: A comparison of religious young men who do versus do not use pornography (2010)

- Viewing Sexually-Explicit Materials Alone or Together: Associations with Relationship Quality (2011)

- Pornography Use: Who Uses It and How It Is Associated with Couple Outcomes (2012)

- U.S. males and pornography, 1973-2010: consumption, predictors, correlates (2013)

- Adolescent religiousness as a protective factor against pornography use (2013)

- Religiosity, Parent and Peer Attachment, and Sexual Media Use in Emerging Adults (2013)

- United States women and pornography through four decades: Exposure, attitudes, behaviors, individual differences (2013)

- The Relationship Between Religiosity and Internet Pornography Use (2015)

- How does religious attendance shape trajectories of pornography use across adolescence? (2016)

- Spousal Religiosity, Religious Bonding, and Pornography Consumption (2016)

- How Much More XXX is Generation X Consuming? Evidence of Changing Attitudes and Behaviors Related to Pornography Since 1973. (2016)

- Religious and Community Hurdles to Pornography Consumption: A National Study of Emerging Adults (2017)

- The Influence of Religiosity and Risk-Taking on Cybersex Engagement among Postgraduate Students: A Study in Malaysian Universities (2017)

- Explicit Sexual Movie Viewing in the United States According to Selected Marriage and Lifestyle, Work and Financial, Religion and Political Factors (2017)

- Pornography Use and Loneliness: A Bi-Directional Recursive Model and Pilot Investigation (2017)

- Seeing is (Not) Believing: How Viewing Pornography Shapes the Religious Lives of Young Americans (2017)

- Sexual Attitudes of Classes of College Students Who Use Pornography (2017)

- Predicting pornography use over time: Does self-reported “addiction” matter? (2018)

- The Use of Online Pornography as Compensation for Loneliness and Lack of Social Ties Among Israeli Adolescents (2018)

- Individual differences in women’s pornography use, perceptions of pornography, and unprotected sex: Preliminary results from South Korea (2019)

As demonstrated here, the preponderance of studies reports far lower rates of porn use in religious individuals compared with non-religious individuals. In fact, comparisons between religious and non-religious rates are not even close.

While this may be true of secular and religious populations generally, could Utah somehow be an exception? Not if you’re paying attention to other relevant evidence specific to Utah. In at least three more recent analyses, Utah’s porn use ranks between 40th and 50th among states:

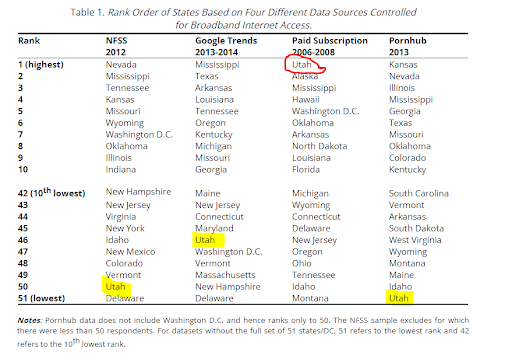

- This peer-reviewed paper confirms the more consistent finding of Utah porn use: “A review of pornography use research: Methodology and results from four sources.” Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace (2015) [see summary chart copied from the paper below]

- Per capita page views, taken from Pornhub in 2014, with Utah listed as 40th (graph available here). Tom Stringham’s own analysis of these same statistics demonstrated that after controlling for a number of additional variables, there is a negative association between porn use in a state and the population of Latter-day Saints (in other words, the higher the Latter-day Saint population in a given locale, the lower the average rate of porn use).

- Researcher Stephen Cranney also provided additional documentation in 2013 of Utah’s low ranking in google trend searches for porn-related topics—with, for instance, the state being dead last in searches for “porn” that year.

Overall, Stringham’s broader summary has stood the test of time:

If critics of Latter-day Saint teachings on porn and sexuality would like to continue promoting the idea that a conservative sexual culture has backfired on itself, then they will have to confront a less convenient set of data. Here is another narrative, that perhaps time and further analysis will prove: Latter-day Saints view less porn than others, and those conservative sexual teachings are working.

That’s precisely what further research and analysis have continued to prove. You wouldn’t know it by hearing from certain experts—but that doesn’t make it any less true. Religious people are substantially less likely to use pornography than non-religious folks.

But in comparison to the rest of the country, Utahns tend to take this problem very seriously, and are doing a lot about it—both preventatively and when people need help to find freedom. That’s undoubtedly a reason people in this state enjoy relatively more freedom from this issue than most—in large part thanks to the ennobling influence of faith permeating our climate.

That’s something to celebrate—and a (true) story to share far and wide to benefit the many others still seeking deeper freedom from the corrosive effects of pornography use in their lives and family. (You can do it! Step by step, moment by moment. Don’t give up!)

Simply put: Life is better without pornography. And Utahns know that better than most.

Notes:

I. None of the foregoing suggests that scientific knowledge is a simple “disclosing” of reality—with individual and collective interpretation relevant from top to bottom, from study conceptualization, to data generation, to analysis and public presentation (see “The Fantasy Story Americans Love to Tell about Science“). What is summarized above is rightly considered the interpretations best warranted by the available data—as concluded by the community of relevant scientific opinion.

II. How, then, are we to make sense of the results of that single study 12 years ago that seems to suggest Utah has a relatively higher rate of porn subscriptions? A couple of factors received far less attention than the scandalous headline. Namely:

- Sampling questions. As Gary Wilson points out, “The original author relied entirely on subscription data from a single top-ten provider of pay-to-view content when he ranked states on porn consumption—ignoring hundreds of other such websites. Why did he choose that one to analyze?” Wilson adds, “We do know that Edelman’s analysis was conducted circa 2007, after free, streaming ‘tube sites’ were operational, and porn viewers were increasingly turning to them. So, Edelman’s single data point out of thousands (of free and subscription sites) cannot be presumed to be representative of all US porn users.” Tom Stringham likewise notes that since the vendor is unnamed in the study, it is “difficult to know if it was a random cross-section of the entire United States.”

As reflected above, it’s likely not. Subscriptions are also not as direct a metric as pageviews when measuring consumption.

- Relative differences. As Stringham and others have pointed out, the relative difference between state rates in the study is slim enough that Utah’s rating (5.47 users per 1,000 people) was not so far above even the lowest state (Montana at 1.92) in the number of subscriptions.

It should also be noted that the zip codes listed in the study with most subscribers do not include those with the highest number of Latter-day Saints, as might be expected if this were predominantly a Latter-day Saint problem. And Stringham also points out that “Idaho (25% Latter-day Saints) had the lowest rate of porn subscriptions per thousand broadband users in the U.S.”—another inconvenient figure only rarely cited.

It’s also relevant to remind people that Utah is hardly a monolithically Latter-day Saint state anymore—with less than 60% of the state identifying with the faith (and a substantial number of those not active).

This visual from the 2015 peer-reviewed paper cited earlier demonstrates how the study above remains an outlier among other reviews.

Referring to this outlier 2009 study, the authors of that 2015 review conclude:

Rankings based on data from a single large paid subscription pornography website have no significant correlation with rankings based on the other three data sources. Since so much of online pornography is accessed for free, research based solely on paid subscription data may yield misleading conclusions.