This summer, I led a survey experiment about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict at the University of Maryland. I gave participants two different versions of the survey—a treatment and a control version. The treatment version contained extra historical information. I hypothesized it would make them more optimistic about the conflict—meaning they would be more likely to predict a peaceful outcome to the conflict than those in the control group. A couple of weeks ago, I spent hours running analyses. I wasn’t seeing any extra optimism. Days later, Hamas attacked Israel.

This was not just any old attack. Hamas attacks Israel frequently. It fires rockets into Israel, and Israel intercepts most of them with its Iron Dome (a rocket defense system). But this time, it was different. It was a slaughter, a massacre. Partiers at a music festival. Communal dwellers living in Kibbutzim. Men, women, and children.

A peculiar people

In 2016, I was hired to help teach a coding class to a primarily Muslim group of refugees in Beirut, Lebanon. As a Latter-day Saint, I shared many values with these students, such as family, sexual ethics, and prophets. I shared many values with these students.

During the course of the class, I heard other things they said too. I heard one friend say his grandfather’s home in Haifa is occupied by the Israeli military. I heard him say he is not permitted to visit—nor anywhere in Israel, the land of his ancestors. It nearly brought him to tears.

When I told them at the end of class that I was going to vacation in Israel, one student responded, “Joe, don’t call it Israel.” Surprised, I waited for her explanation. “Whatever you have heard, we were here. We know what happened. They stole our land.”

I loved my visit to Israel. I found the land magical. How could I not call it Israel? Where was she coming from? How could this perspective come from the warm, utterly hospitable culture I had visited?

Through Arab eyes

My curiosity led me to study Arabic at one of the top programs in the nation. I traveled to Amman, Jordan, as part of my study. There I had the opportunity to learn more about the conflict both through the lens of those I lived near and through my study.

I learned that Theodore Herzl, the father of Zionism, had responded to the hundreds of years of persecution of the Jewish people, especially in Europe, by declaring that, finally, to establish safety for their people, the Jews needed their very own nation. His words reverberated like a clarion call in the late 1800s. The Zionists considered multiple geographies but settled on Palestine, home of the prophets in the Torah.

Hundreds, thousands, and then hundreds of thousands flocked to the cause. They bought up land with a large hub around what is now Tel Aviv. That land, called Palestine, had been ruled by the Ottoman Empire, which fell in World War I. After that, the British ruled it in what was known as Mandatory Palestine. The British had allied themselves with groups of Arabs as well as with the Zionist Jews. Then the British Balfour Declaration decreed in 1917 that “His Majesty’s Government view[s] with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” and would endeavor to bring it about.

More Jews came to Palestine. Their number swelled into a large population—the kind of population that could form a small nation. Tensions grew between the Palestinians living there and their new neighbors—though other Jews had already been living in Jerusalem and enjoying a mostly peaceful coexistence. These new neighbors were different in that they came to seek refuge and a newly forming nation.

Both Jews and Arabs wanted the British to leave and got their wish when Britain no longer had the resources to maintain control of the area after World War II. In 1947, the United Nations proposed a partition plan to divide the area into a Jewish and Arab state. But the Palestinians rejected the plan. In 1948 Israel declared itself a nation with the backing of the United Nations, and the First Arab-Israeli War broke out. As a result of the war, seven-hundred-thousand Palestinians were expelled from their houses and land. To this day, generations later, millions of Palestinian refugees and their descendants live in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, unable to return to that land. This history is felt deeply.

This history is felt deeply, not just by Palestinians but many Arabs who, as Dr. Shibley Telhami explains, yearn for dignified treatment but feel they have received none.

Growing up with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

As a child, I didn’t have the same historical perspective of the conflict. People tried to explain by saying they had pretty much always been fighting since ancient times. That seemed fair enough; I had no reason to question it. The other reason given was that Israel was constantly under a barrage of terrorist attacks. We all agreed that the Israelis should be able to defend themselves.

But while I, and many like me, believed the Palestinian attacks were motivated by hatred, the Palestinians themselves saw them as fighting for their homes that had been stolen from them.

Throughout this, the Palestinians who requested reparation peacefully were drowned out by the very real threat of terrorism.

Impending devastation

Hamas, which took political control of the Gaza strip in 2007, brutally killed and injured thousands of Israeli citizens in an October 7th terrorist attack and took over two hundred hostages. Hamas was, in part, explicitly founded to destroy Israel. Israel’s reaction was swift. It regained control of its territory and fired rockets into Gaza. Many Hamas militants were killed. Unfortunately, thousands of Gazan civilians also were injured or killed.

In the wake of the attack, Israel’s position is to remove Hamas from Gaza to ensure their safety. The impending war is set to exacerbate a civilian catastrophe in Gaza.

Thousands of citizens have been killed. Civilian casualties have historically been very high in Israel’s attacks against Hamas because of the organization’s use of human shields and Israel’s proclivity to strike notwithstanding. Israel has ordered a million Gazan residents to evacuate. But with the borders to both Egypt and Israel closed, they have nowhere to go. Meanwhile, food, water, and essential supplies are in critically short supply. Israel has severely limited the aid entering Gaza, wary of reports that Hamas often confiscates humanitarian supplies while Hamas is preventing local fuel sources from going to ordinary citizens. Humanitarian agencies predict even worse conditions ahead for Gazan civilians.

Seeing Palestinian pain

In the experiment I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, I found the treatment (additional historical information) did not make participants more optimistic about a peaceful resolution. There were other statistically significant results, however.

I gauged participants’ feelings of warmth (approval) for the Palestinian people and Israeli people (while distinguishing them from their governments). When experiment participants received the extra two paragraphs of historical information, levels of warmth increased for the Palestinian people significantly, with no drop in warmth for the Israeli people. What was that extra bit of information? It simply dispelled a common myth about the conflict. Students were told that despite frequent claims to the contrary, the Israelis and Palestinians have not been fighting since ancient times and that the First Arab-Israeli War was in 1948.

Regardless of the ultimate conclusions about the conflict, Palestinian grievances are more than mere hatred for Israelis. Their motivations can be articulated without reducing them to caricatures. Their claim is one of stolen land and forced evacuation. They want a good life for their families. They want to be treated with dignity.

Safety and security

Acknowledging the Palestinian people’s articulated pain does not weaken the Israeli argument. Hamas preys on the grievances of Palestinians. And they maintain their power by weaponizing the harm done by Israel’s retaliatory strikes. The more Gazan civilians die, the stronger Hamas remains. Israel can weaken Hamas by committing to reduce civilian casualties.

Fatah, a rival to Hamas in Palestine, has recognized Israel’s right to exist and has made productive moves toward peace in the past. The protection of Palestinian civilians and a recognition of Palestinian grievances could serve to empower Fatah at the expense of Hamas.

Making the Hamas fight deliberate, strategic, and precise rather than reducing half of the Gaza Strip to rubble will prove more effective for the long-term peace and security of the Israeli people. Their motivations can be articulated.

A religious perspective revisited

This pragmatic approach is often complicated by a religious understanding held by many Christians that Israel would return someday to their promised land.

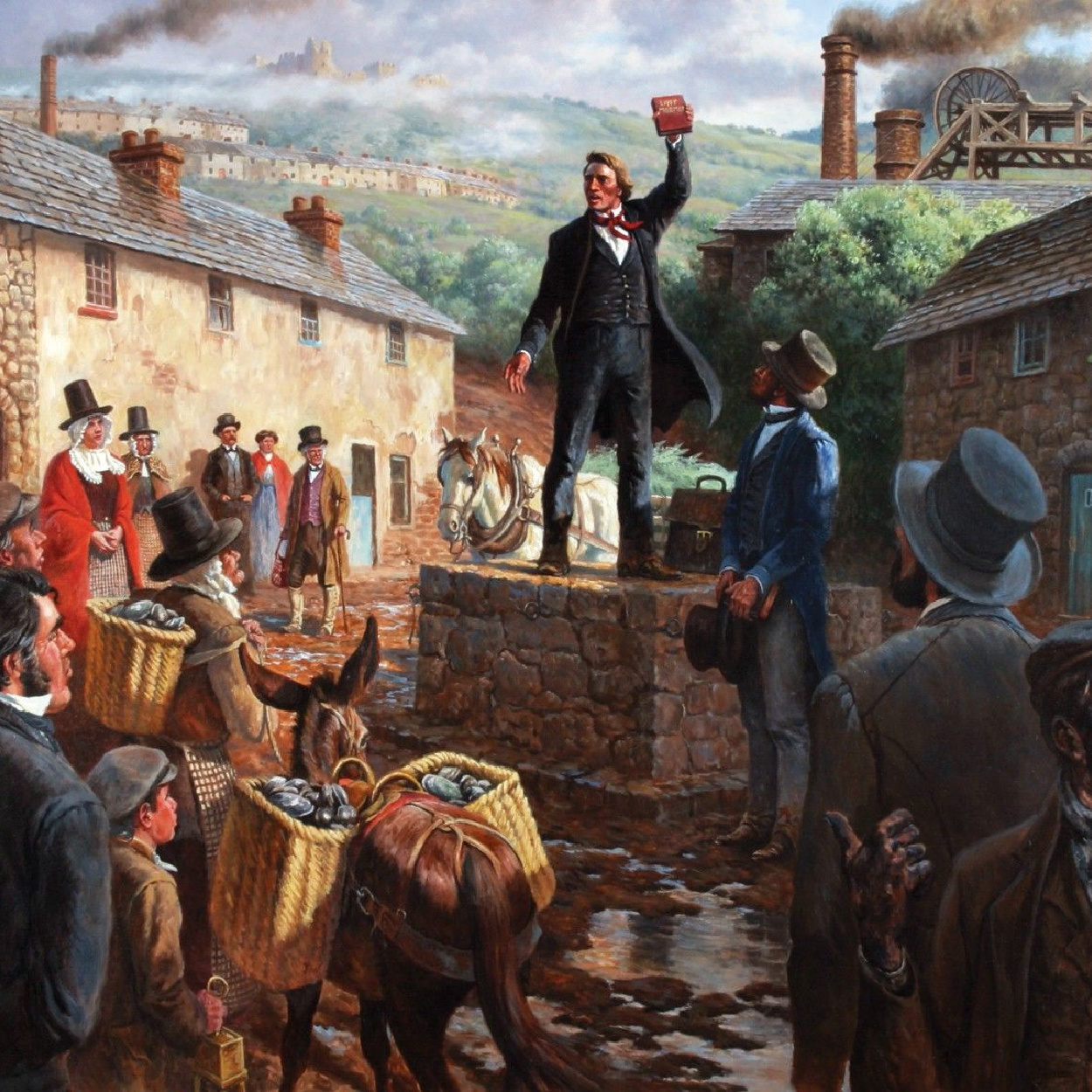

In fact, Joseph Smith called Orson Hyde, an early apostle, on a special mission to travel to Jerusalem to bless the land for the return of the tribe of Judah. It is easy to see the Palestinians as a force trying to thwart the will of God, knowingly or unknowingly.

However, this prophecy does not dictate specific timelines or strategies.

Doctrine & Covenants 85:8 warns against steadying the ark, invoking the biblical account of Uzzah, who touched the Ark of the Covenant though he was forbidden to. The lesson may be that we err by taking it into our own hands to fulfill prophecy.

Captain Moroni, a prominent Book of Mormon figure, demonstrated that military gains can be accomplished through preserving life.

Howard W. Hunter taught in 1979:

“Both the Jews and the Arabs are children of our Father. They are both children of promise, and as a church, we do not take sides. … The purpose of the gospel of Jesus Christ is to bring about love, unity, and brotherhood of the highest order.”

Some years later, Hunter invited Bonner Ritchie, a BYU professor, to “build bridges to the Palestinians.” According to Ritchie’s account, Hunter “said there would be a period of peace prior to the Second Coming and that we should be part of creating that peace.” This year, President Russell Nelson charged disciples of Christ to be peacemakers and to build “bridges of understanding.”