In every community of every kind, there are values, commitments, and ideas that unite them. And for this reason, every community must grapple with the question of what to do with those among them who decline and reject these offerings.

Religious history is filled with tragic examples of the worst offenders in this regard, from crusades and inquisitions to martyrdoms and crucifixions. But it was the most famous of these violent rejections that ultimately highlights another “father-forgive-them” alternative. At the heart of the Christian message, in particular, is an aspiration to regard even our enemies with love.

For most Christian communities, this remains the standard: grace, forgiveness, gentleness, and compassion to those who have gone astray, including the apostate and the heretic. While it’s true most faiths have boundaries that can be crossed to the point of various stages of disfellowship, most believers still regard those rejecting these community norms as former brothers and sisters to be reclaimed.

Sinners of all kinds, in this view, are to be met with compassion and a hand of fellowship always outstretched. As many observers have noted, this is a noticeable contrast to how the unorthodox are regarded by those fervently committed to the popular ideology of social justice.

Problematic people. Although it’s hard for anyone to see loved ones rejecting beliefs they themselves cherish, a long view of the future can encourage patience and compassion. “Religion, in part, is about distancing yourself from the temporal world, with all its imperfection,” Shadi Hamid writes of monotheistic religion today. “At its best, religion confers relief by withholding final judgments until another time—perhaps until eternity.”

By contrast, Hamid continues, “The new secular religions unleash dissatisfaction. … If matters of good and evil are not to be resolved by an omniscient God in the future, then Americans will judge and render punishment now.”

Much like religious leaders wielding judgment from a place of unique callings, John McWhorter tells Helen Lewis, “The hyper-woke—who were firing people right and left, and shaming people right and left—think that they’re seeing further than most people, that they understand the grand nature of things better than the ordinary person can”—adding, “To them, they’re elect.” In his book, McWhorter identifies this as a “priestly class” of influential writers and politicians who dictate the rules of what can and cannot be said. Religion confers relief by withholding final judgments.

Compared with mere “sinners,” of course, apostates and heretics bring up other issues, like what religious communities should do if somebody actually is undermining the community with false preaching—or not embracing some of these brave new teachings.

For instance, McWhorter suggests that teachings around privilege (white privilege or male privilege being inherited problems) are versions of original sin—a stain that humans are born with, no matter their individual circumstances.

With any strong dogma, of course, people can become animated and passionate in their agreements and disagreements. And Helen Lewis points out how established religions have developed strategies for dealing with enthusiasm that shades into zealotry—quoting Rabbi Laura Janner-Klausner, of the Bromley Reform synagogue in south London, who said, “In religious life, or Jewish life, the person you sit next to in synagogue may drive you completely potty, they may be so annoying and have different views, and you must still go to their family’s funeral.”

This kind of geographical networking has a way of mediating and dampening conflict. As Lewis continues:

In real life, churches, mosques, synagogues, and temples force together, in their congregations, a random assortment of people who just happen to live close to them. But today’s social activism is often mediated through the internet, where dissenting voices can easily be excluded. We have taken religion, with its innate possibility for sectarian conflict, and fed it through a polarization machine. No wonder that today’s politics can feel like a wasteland of anguished ranting—and like we are in hell already.

The stigma of being on the wrong side. No wonder those on the other side can feel like they’re in such a tight and uncomfortable place indeed. Helen Lewis describes a conversation with Alex Clare-Young, a nonbinary minister in the United Reformed Church, about whether expressing faith or gender was more surprising to Generation Z acquaintances. Clare-Young responded that admitting religious commitments was “probably” harder—adding, “I know a lot of LGBTQ+ young people who say it’s harder to come out as Christian in an LGBT space than LGBT in a Christian space.”

Noting that “politics has now crept into every aspect of our lives,” the Atlantic journalist Helen Lewis recounts, “In countries where racial and religious intermarriage have become commonplace, dating across political lines is the new taboo”—with more and more dating profiles now insisting, “no conservatives.” Lewis cites Victoria Turner, the editor of an anthology titled Young, Woke and Christian, as saying she could happily date someone from another faith or no faith at all. But a conservative?

“Absolutely not. No.”

Certainly, there are plenty of conservatives who would feel the same way about dating a hard-core progressive—and religious parents who would agonize over their children dating someone from a different tradition, especially if they have left their own faith.

In the absence of common ground appreciation of a gracious God with future possibilities of redemption, how else can we encourage more compassion and patience with some of these differences?

Perhaps simply by talking about these differences more openly.

Taking social justice for granted as universal—the pressure this prompts. As mentioned earlier, almost no one talks about social justice as a religion. John McWhorter notes this is not unusual historically:

In 1500, nobody in Europe considered themselves religious. It was just in the water. If there was such a thing as an atheist, they kept that to themselves … that’s where we are now. And so many of the people now who are religious would resist the label because especially a modern, secular, educated person often won’t like the idea of being told that they have a religion. But that doesn’t mean that the analysis isn’t accurate. There’s a religion.

If social justice ideology is so much in the air that people aren’t even paying attention to it, that would apply to people who are participating in other religious systems too. And referring to these new social justice commitments, Tom Stringham writes, “In most cases, believers simply do not know they are a part of it. Even most non-believers don’t see the religion for what it is.” As a result, these new beliefs and convictions can get passed along as basic decency, goodness, and love—rather than a particular philosophy any of us can simply disagree with.

This underscores the danger when people see something as universal—and, therefore, not to be questioned. Compared with Catholicism which Stringham remarks is “contextualized in our society as a religion, and people are thus entitled not to believe in it,” contemporary American progressivism is not contextualized as a religion or even as a worldview—to believers, it’s understood as “literally just being a decent person.”

Accordingly, adherents tend to expect everyone to live as if their beliefs are true. At best, he continues, this will lead others to “come to (mistakenly) believe our religion to be consistent with theirs. At worst, the Christian believer converts himself to the other religion by unwittingly participating in it.”

Calling social justice a “religion” creates new space. All this helps explain why calling this other system of thinking a new religion could be so helpful. As Tom Stringham explains further, this would give this ideological approach the “same social status” as other religions: “Specifically, you don’t have to convert to it, the same way other people don’t have to join our church. You can respect the religion, see what is good about it, and still decline to participate in its customs or adopt its worldview.”

He goes on to explain more of the practical benefits:

Many of us have been asked at some point why we don’t use a symbol or term when it “just means” equality, kindness, or respect. We may find it difficult to answer. But Latter-day Saints could just as well ask others why they don’t wear, say, CTR rings, which, after all, “just mean” that we should choose the right. But we know why: other people don’t wear CTR rings because they are not part of our religion. They may not object to the nominal meaning of a CTR ring, but that doesn’t mean they need to wear one. Neither should church members feel obligated to participate in the customs of religions we aren’t a part of, let alone customs that may cause tension with our own religious beliefs.

Among other things, this “reminds us that believers in the other religion deserve respect, the way Muslims or Catholics or Hindus do. It also permits us to identify the truths that exist within the religion.”

This, furthermore, can help us navigate conflicts that arise, especially the degree to which these center on ideological combat between traditional religions as this insurgent ideology.

Greater awareness can thus generate greater space and recognition that “the unique teachings of contemporary American wokism should not be simply accepted.” For instance, Stringham points out that within social justice ideology, “maleness and femaleness, qua the social categories we are all familiar with, are, in fact, categories of gender identity, a gnostic sense of one’s identity that is perfectly knowable by the individual but not verifiable or falsifiable by others, even in principle.”

Yet like distinctive teachings of other faiths, “This is a strong, arguably supernatural teaching which should not be simply accepted unless it is part of a conscious, deliberate conversion to the woke religion.”

More than simply guarding against undue pressure, this kind of transparent acknowledgment can also help “avoid accidental conversion.” The need for redemption is left behind in secular religion.

The need for redemption. Thus we see that important things are being left behind in secular religion when it comes to how to approach those rejecting its dogmas. When asked about how social-justice movements might adopt some of the “good bits” of religion, Helen Lewis says, “As somebody who was raised in the Catholic Church, I did see the way that it made sure that people were looked after. There were bonds between people, a sense of community, and also a sense of shared values.”

“Can religiosity be effectively channeled into political belief without the structures of actual religion to temper and postpone judgment?” Shadi Hamid asks, before answering his own question: “There is little sign, so far, that it can.” He then added, “If only Americans could begin believing in politics less fervently, realizing instead that life is elsewhere.”

In addition to seeking a deeper source of meaning and value, Lewis added, “I think if we want people to genuinely own their mistakes, then you have to offer the possibility of redemption.” She continues, “I think what we have now with social-justice movements is a range of sins, but we don’t yet have a good idea of what the mechanism is for confessing, repenting, and being absolved.”

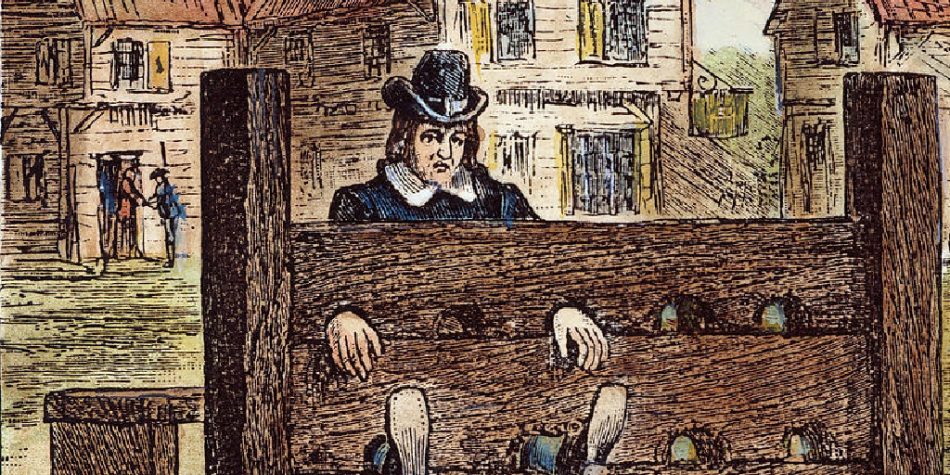

Could that still be developed in the social justice future? There is little evidence of this on the horizon of this new system of thought. In the absence, as John McWhorter laments, “We seek change in the world, but for the duration will have to do so while encountering bearers of a gospel, itching to smoke out heretics, and ready on a moment’s notice to tar us as moral perverts.”

No wonder so many of us are watching our backs these days! Indeed, by many accounts, a new inquisition is afoot. But in this case, it’s an inquisition that doesn’t even admit it’s taking place.

So, how will you be judged in this new religious regime? Even more importantly, how willing are you to be patient and compassionate with those who see you as a dangerous threat to their vision of the ideal society?