Christianity in the Twentieth Century

Brian Stanley

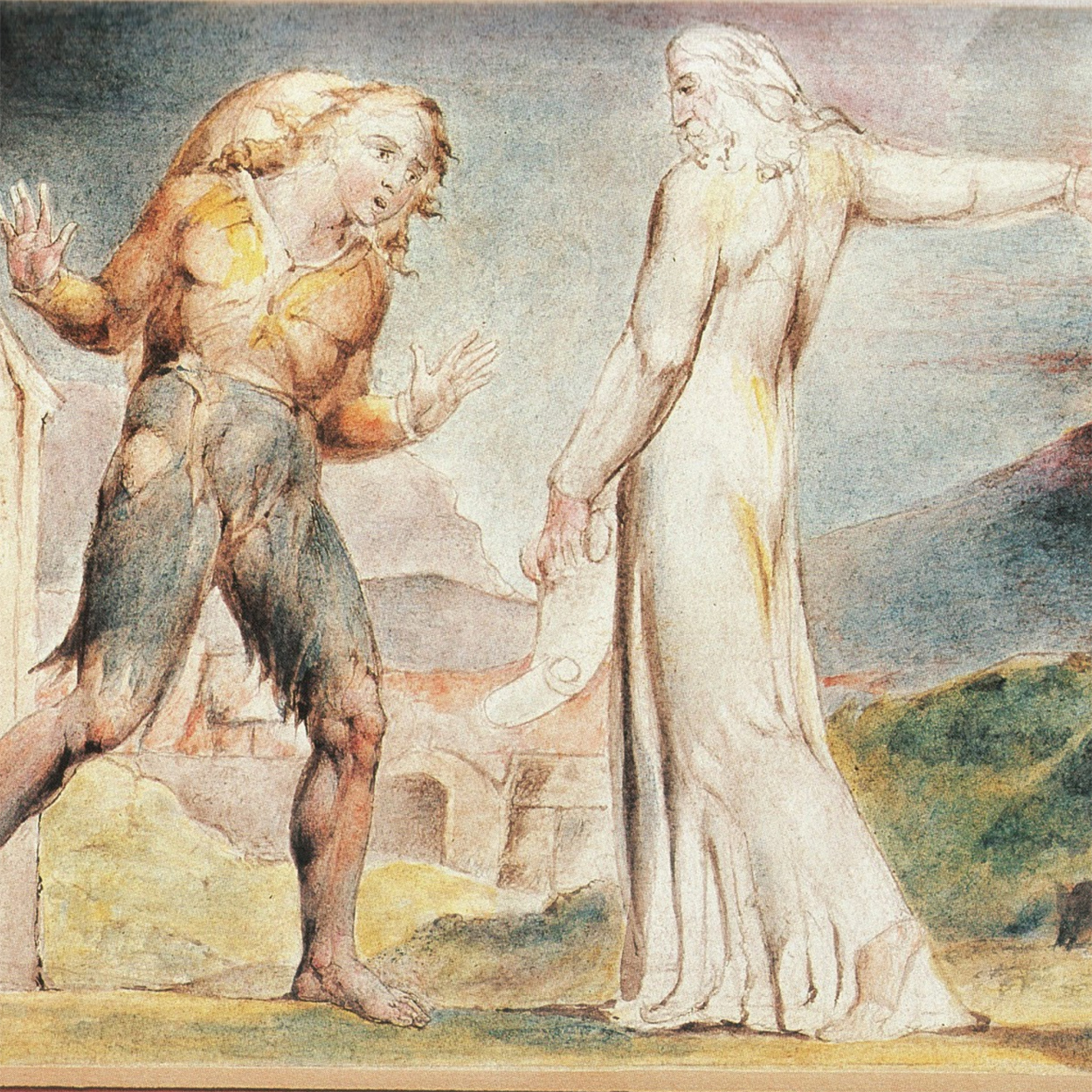

Stanley, studying the complicity of the Christian Church in the Holocaust and the Rwandan genocide,

draws this important conclusion about Christians and proximity to political power:

“Christians often look for inspiration for their guidance in political behavior to the Hebrew prophets, who fearlessly declared the word of the Lord to king and nation, often at risk to their own lives. The hopeful expectation is that the churches should display similar theological fidelity and moral courage, but it tends to be forgotten that the Old Testament prophets were often isolated and deeply unpopular figures. Effective prophetic speech depends on a paradoxical balance between maintaining access to the sources of political power and preserving sufficient distance from those sources to enable moral independence to be safeguarded. Both the cases discussed in this chapter [the Holocaust in Nazi Germany and the genocide in Rwanda] suggest that wherever churches have become large and influential human institutions, they tend to prioritize the maintenance of political access over the safeguarding of moral independence. … [An] awareness of sinfulness ought to lead Christians, not in the first instance to censure the behavior of others, but to continual self-criticism and repentance… Christianity proclaims a gospel of redemption from sin, but what Christians find hardest of all is to recognize the extent to which evil can infect even the company of the redeemed.”

Novels, Tales, Journeys: The Complete Prose of Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Pushkin

Two gems from the prose of Alexander Pushkin are as relevant now as they were 200 years ago.

First, in “The History of the Village of Goryukhino,” we read a caution against seeing the past through a hagiographic lens: “We should not be seduced by … charming picture[s] [of the past]. The notion of a golden age is inherent in all people and proves only that they are never pleased with the present and,

experience giving them little hope for the future, adorn the irretrievable past with all the flowers of their imagination.”

And in “Roslavlev,” we encounter an insight relevant to today’s multitudes who are in a constant state of frenzy by keeping too close to 24-7 news coverage. “Surrounded by people whose notions were limited, constantly hearing absurd opinions and ill-founded news, she fell into deep despondency; languor took possession of her soul. She despaired of the salvation of the fatherland, it seemed to her that Russia was quickly approaching its fall, each report redoubled her hopelessness.”

The present has always been messy. But it’s never so bad that hope is lost. A focus on ultimate things—the stuff that stands above the smog and shifting terrain of everyday life—keeps our souls on solid ground.

Celebration of Discipline

Richard J. Foster

“Superficiality is the curse of our age.” So begins Richard J. Foster’s classic 1978 work on spiritual

growth via the disciplines of meditation, prayer, fasting, study, simplicity, solitude, submission, service, confession, worship, guidance, and celebration.

“The doctrine of instant satisfaction is a primarily spiritual problem. The desperate need today is not for a greater number of intelligent people, or gifted people, but for deep people,” he writes.

How does one attain such depth if, as Foster says, the work of inner transformation is uniquely God’s to bring to pass? Foster’s take on the grace-works debate is smart and inspired. “The analysis is correct—human striving is insufficient and righteousness is a gift from God—but the conclusion [that no effort on our part is required] is faulty. Happily there is something we can do. We do not need to be hung on the horns of the dilemma of either human works or idleness. God has given us the Disciplines of the spiritual life as a means of receiving his grace. The Disciplines allow us to place ourselves before God so that he can transform us. … If we ever expect to grow in grace, we must pay the price of a consciously chosen course of action which involves both individual and group life. … We must always remember that the path does not produce the change; it only places us where the change can occur. This is the path of disciplined grace.”

Persuasion

Jane Austen

This novel moves slowly, but such is the price we pay to discover enduring wisdom. And that is precisely what we get from the main character, Anne Elliot.

While among others who ask her questions as a way to talk about themselves instead of hear her speak, she senses the need of “knowing our own nothingness beyond our own circle.” After extending a listening ear to Captain James Benwick in his time of sorrow, she comes away with a humbling epiphany. “When the evening was over, Anne could not but be amused at the idea of her coming to Lyme to preach patience and resignation to a young man whom she had never seen before; nor could she help fearing, on more serious reflection, that, like many other great moralists and preachers, she had been eloquent on a point in which her own conduct would ill bear examination.”

Later, reflecting on a difficult moment endured in the beautiful coastal town of Lyme, Anne shares a

thought that we would want to be said of our time here on earth. Yes, we experience pain and misery. But in the end, we hope to look back and see growth and joy.

“The last few hours [in Lyme] were certainly very painful, but when pain is over, the remembrance of it often becomes a pleasure. One does not love a place the less for having suffered in it, unless it has been all suffering, nothing but suffering, which was by no means the case at Lyme. We were only in anxiety and distress during the last two hours, and previously there had been a great deal of enjoyment. So much novelty and beauty! I have traveled so little, that every fresh place would be interesting to me; but there is real beauty at Lyme, and in short, altogether my impressions of that place are very agreeable.”

The Storm-Tossed Family

Russell Moore

Dr. Moore of the Southern Baptist Convention wrote this book to help people understand how family—a potential source of both transcendent joy and excruciating pain— is an echo of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

“Your family might bring you pain,” he writes. “What of it? To love is to suffer. But you have learned

that suffering is not a sign of God’s absence but his presence. You learned that at the Place of the Skull. … Your family will lead you where you never expected to go. But this is no reason for fear. The path before you is the way of the cross. … The way of the cross leads Home. … Whatever storms you may face now, you can survive. If you listen carefully enough, even in the scariest, most howling moments, you can hear a Galilean voice saying, ‘Peace. Be Still.’ If you give attention to more than just the wind and the waves, you might see some hands reaching out for you. In fact, you may notice that those hands already have you, holding you safely above the waters below. You are not as tossed about as you think you are. If you stop to recognize it, you just might notice that those hands holding on to you have spike- holes. Do not be afraid. The scars remain, but the storm has passed.”