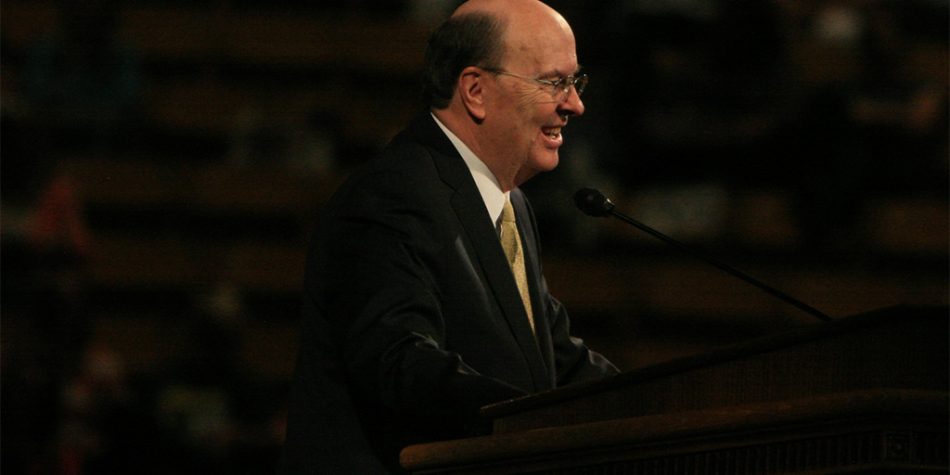

In an October 2020 address at the semiannual General Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ, “Hearts Knit in Righteousness and Unity,” Elder Quentin L. Cook explains how to draw upon goodness and unity to achieve a kind of “diversity” that can avoid the “iniquity and division” that destroyed the Zion society of 4th Nephi and that roils society today in the United States and many other countries. “With our all-inclusive doctrine, we can be an oasis of unity and celebrate diversity,” he teaches. “Unity and diversity are not opposites. We can achieve greater unity as we foster an atmosphere of inclusion and respect for diversity.” Among the doctrines that favor righteous unity as a basis for diversity, Elder Cook includes the teaching that “the host country for the Restoration, the United States, the U.S. Constitution, and related documents, written by imperfect men, were inspired by God to bless all people.” Today, of course, this doctrine has become very controversial, and a powerful movement pits the progress of diversity and justice against the legacy of the Founders’ Constitution.

Elder Cook acknowledges that our American Founding documents were “written by imperfect men.” How, then, are those striving for a Zion society of righteousness and unity, to understand the imperfections of our political founders and forbears, as well as those in our present constitutional order? Elder Cook shed much light on this question, and its relevance to higher education in the Church, in a speech he gave just weeks before his General Conference address. Those who did not hear Elder Quentin L. Cook’s BYU opening conference address, 20 August 2020, should hear or read it. To those who did hear it, I recommend reviewing it, probably more than once. Elder Cook’s counsel, at once mild and pointed, is both wise and timely; I would even say his inspiring advice is essential in our tumultuous times, buffeted as we are by contending ideologies and moralities (Any arguments or inferences presented here beyond what is intended by Elder Cook’s speech are of course my responsibility, and not his).

As is customary in these university conferences, the two featured speeches, the first by University President Kevin Worthen, and the second by Elder Cook, were complementary in the focus of their concerns. President Worthen addressed BYU’s educational mission, considered on its own terms and largely apart from external influences and incentives. Elder Cook, on the other hand, plainly and directly situated BYU’s mission in the context of the challenges presented by the passions and beliefs at work in the world around us.

It is clear that the alternative current dominant in higher education is one that fosters criticism of the Church and its leaders

In introducing his theme, “Be Not Weary in Well-Doing,” Elder Cook cited Elder Kimball’s bold challenge in his 1967 address to BYU’s faculty and staff: “You will see the day that Zion will be as far ahead of the outside world in everything pertaining to learning of every kind as we are today in regard to religious matters.” This statement is unabashed, first, in affirming that in an important sense we are “far ahead of the outside world … in regard to religious matters,” and second, in defining our educational mission, not as keeping up with the world’s most prestigious institutions, but in some sense out-distancing them. Elder Cook then notes that essential to our moving “far ahead” will be “maintaining a ‘laser-like focus’ on our responsibility to help build faith in Jesus Christ and in His restored Church. …” He notes that the university must face certain “specific challenges” in order to maintain this focus and to move ahead of the world:

First, the adversary constantly throws up obstacles to faith.

Second, he creates alluring alternative visions that are based on the wisdom of the world and that will be viewed favorably by many who are well educated.

Third, he attempts to confuse faithful and stalwart adherents as to what they should do and what they should say.

The second, central challenge strikes me as especially critical for considering BYU’s mission: education itself, as the world increasingly conceives it, risks presenting alluring alternative visions to our laser focus on faith in Christ and his Church. The rest of Elder Cook’s speech helps us understand the precise character of the alternative to faith that is increasingly dominant in higher education.

From his remarks that follow, it is clear that the alternative current dominant in higher education is one that fosters criticism of the Church and its leaders from the standpoint of some conception of social justice, and in particular racial justice. In his first response to this kind of criticism, Elder Cook cites Church historian Matt Grow to counsel humility in our judgments of past leaders:

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” . . . That means when we visit the past, we don’t want to be an “ugly tourist.” We want to try to understand people within their own context and their own culture. We want to be patient with what we perceive as their faults. We want to be humble about the limits of our own knowledge. And we want to have a spirit of charity about the past.

To moderate our judgment of past leaders is to recognize that we ourselves are deeply fallible, not only in our personal character but in the very moral categories by which we would judge others.

Humility and moderation in judging others, Elder Cook suggests, is essential to the task of “creating unity and being grateful for diversity… build[ing] bridges of cooperation instead of walls of segregation.” But these virtues are clearly in short supply, so Elder Cook proceeds to counsel us in “determining how to deal with criticism.” It is here that he introduces a richly suggestive literary example, Anthony Trollope’s The Warden. In this novel, the warden, the Reverend Septimus Harding, is responsible for a small “hospital” or home for a dozen elderly men, on behalf of the Church of England and therefore of its local officers, the warden’s superiors, the bishop and the archdeacon. These authorities are confronted with a staunch young reformer, aptly named Dr. Bold, who, Elder Cook explains (citing Trollope):

…could not “be brought to believe that old customs need not necessarily be evil, and that changes may possibly be dangerous.” Trollope further stated that Bold “hurls his anathemas against time-honoured practices with the violence of a French Jacobin.”

“Does that not sound somewhat familiar,” Elder Cook asks, “whether from the left, the right, the secular, and, in some cases, even the religious.” (My emphasis.) What we are asked to recognize as familiar is the tendency to bold moral judgment, judgment that lacks humility and moderation and thus fails to respect the good purposes served by settled customs and the institutions they support. And Elder Cook seems to hold up Reverend Harding as an example precisely for his humility in responding to Dr. Bold’s criticism and legal action against the Church; in this Harding is contrasted with the archdeacon, Dr. Theophilus Grantly, “who vigorously headed the defense of the church. …”

[T]he Reverend Septimus Harding, the warden of the hospital, was described as a kind, “open-handed, just-minded man” who felt “that there might be truth in what had been said.” Harding wanted to be moral and right with the Lord. Some have described him as having “persistent bouts of Christianity” and being a true Christian.

Consulting the novel, we better understand Elder Cook’s comparison. We learn that what distinguished Reverend Harding’s character was his self-effacing response to criticism of the Church in which he and his comfortable livelihood were implicated. When a diocese of the Church of England, and he as its representative, was accused of benefiting unjustly from the great increase of the value of Church property over four centuries, while the elderly patients continued to receive only the basic benefits of food and shelter, Harding, unlike his superior, the archdeacon, did not seek to discredit his accusers, but in fact was willing to acknowledge that there might be some truth in the charges; in fact he went so far as to abandon the property and living he enjoyed along with the specific calling that went with it. This was then the expression of the warden’s “bout of Christianity.”

Elder Cook likens Harding’s humble response to responses to criticism by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

We are certainly among the least aggressive in defending ourselves against obviously untrue and/or unfair criticism. I offer as exhibit A our decision or lack of decision to react to The Book of Mormon musical. One leader of another faith pointed out to me that there is not another religion that would not have responded with a hailstorm of righteous indignation at the crude, vicious, and reprehensible portrayal of our faith and of our missionaries. Rather than organize a major protest or boycott, the Church bought ads in the playbill that simply said, “You’ve seen the play . . . now read the book,” and showed a picture of the Book of Mormon.

Maybe “persistent bouts of Christianity,” a heartfelt desire to be true Christians, and a determination to turn the other cheek are the only plausible answers to my friends who raise this question.

Interestingly, however, Elder Cook does not leave the matter there.

On a more serious note, a principal purpose for me today is to encourage you in your efforts to bless and guide the rising generation and to correct falsehoods and matters taken out of context in a loving and kind way. There will be some occasions when we need to speak publicly to protect faith. …

Unlike Reverend Harding, then, Elder Cook makes it clear that the disposition to “turn the other cheek” does not imply simply conceding to our critics regarding the accusations in question.

Just because the Church or BYU administrators do not respond, never assume that the criticism is justified. As I have indicated, many criticisms are not worthy of a response. And in many cases, the Christian thing to do is to not respond and to turn the other cheek. Some critics have a record of opposition that is so dogmatic, persistent, and unfair that Elder Bruce R. McConkie once famously noted that the dogs keep barking and “the caravan moves on.”

Elder Cook’s counsel regarding responses to criticism of the Church is thus far from identical with the approach of Reverend Harding in Trollope’s The Warden. While counseling mildness and sometimes even silence in the face of criticism, the apostle clearly encourages saints, especially those responsible for the education of young Latter-day Saints, to “correct falsehoods and matters taken out of context in a loving and kind way;” our “laser-like focus” on building faith will sometimes include speaking out, unlike the warden, in public in defense of the Church.

A closer look at Trollope’s novel, beyond the few elements of the story shared by Elder Cook in this speech, will shed further light on the problem of defending the faith while also being ready to humbly turn the other cheek. But let us first briefly note the examples Elder Cook goes on to provide of correcting falsehoods and understanding context. He introduces these examples with the following striking observation:

Understanding moments when we have been marginalized and persecuted should give us courage to stand with the marginalized today, “to bear one another’s burdens,” “to mourn with those that mourn,” and to “comfort those that stand in need of comfort.”

By prefacing his examples in this striking way, Elder Cook underscores the significance of the philosophical alternatives we face, influenced as we are by the ideologies prevalent in higher education. Few local viewers or readers of this talk will fail to notice that “mourn with those that mourn” has become a favorite Latter-day Saint addition, on protest and yard signs, to the movement slogan “Black Lives Matter.” Elder Cook naturally approves the prophet Alma’s teaching, but he also immediately distances its meaning from the Manichean ideology of the movement, in which the moral line between good and evil which, as Alexandr Solzhenitsyn observed, runs right through every person’s heart, is replaced by the ideological line between Black and White. He does this by first acknowledging the “devastating personal impact and societal consequences of slavery,” and then going on to recount two features of our history as Latter-day Saints: he reminds us of the persecutions the Saints themselves have suffered (though these are not “comparable” to those of slavery), and at the same time he shows us that these persecutions were partly a consequence of our sympathy for Native Americans and our disapproval of slavery. The effect of these reminders is, again, to point beyond the exclusive association of “black” with victimhood and of “white” with the part of oppressors. It is to suggest that mourning with those that mourn cannot be confined to racial and ideological categories.

Elder Cook then goes on to consider the case of Brigham Young, the very namesake of the university the apostle is addressing. Again, few who listened to this address could have been unaware that voices had recently been heard calling for changing the name of the university because of Young’s alleged racism. The least one can say is that Elder Cook did not appear receptive to such a suggestion. Providing an example of the moderating historical contextualization he had earlier recommended, he acknowledged Pres. Young as a prophet, praised his “practical and organizational genius… but more than that [the fact that he was] a deeply spiritual leader,” noted his often respectful and benevolent regard for Native Americans, but then candidly acknowledged that “Brigham Young also said things about race that fall short of our standards today.” (This formulation, we might note, obviously contextualizes Pres. Young’s racial views, but also, less obviously, invites the reader to contextualize “our standards today,” to recognize, that is, that our present understanding, on which our judgments of racism are based, may not simply represent the final pinnacle of morality.)

Clearly neither Trollope’s nor Elder Cook’s sympathies are with the reformer Dr. Bold, whose reforming zeal is said to partake of the imprudent and destructive revolutionary spirit of the French Jacobins

Elder Cook then recounts his experience with race issues, going back to his experience at age 17 in Washington, D.C., as a Utah Boys Nation senator, where he met President Eisenhower, as well as future presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. His declaration of admiration for the Republican President Eisenhower, especially for his ordering the integration of Little Rock Central High School later in 1957, has the effect of putting our quest for racial justice in a broader context and lifting it above the agitation of today’s young social justice warriors. Similarly, Elder Cook’s review of his Church experience, going back to his missionary service in the early 1960s in the British Mission under Marion D. Hanks, reminds us that commitment to racial equality is far from a recent discovery or the property of the radical left. “That was our doctrine then and that is our doctrine now,” he affirms. To much the same purpose, he goes on to remind us of “the overwhelming approval and gratitude across the entire Church” that greeted the 1978 revelation abolishing racial restrictions on priesthood ordination, and then affirms that in forty-five years of Church leadership he has “never heard a racially derogatory comment from a single leader of the Church,” but rather “love, kindness and respect for peoples of all races and cultures.” Clearly warning “that some people involved in today’s various movements are deeply opposed to religion and people of faith,” he goes on to remind us of the essential role played by Christian faith in the cause of racial justice from William Wilberforce in early nineteenth-century England to Martin Luther King Junior in the American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s. One central point of Elder Cook’s speech is that the aspiration for racial justice can be joined with “greater civility, racial and ethnic harmony and mutual respect” only if the deeply Christian origins of this quest are respected.

How, then, should we as Christians understand our social and political responsibilities? This is the more fundamental question that lies beneath Elder Cook’s advice on dealing with criticism of the Church and of our faith. To address it he has first invited us to “view this issue from a more distant perspective.” “Good literature,” he has suggested, “often challenges us but can also give us guidance on how to respond.” He then has proposed, as we have seen, that Anthony Trollope’s The Warden might help us achieve such a perspective. “One of my purposes in sharing the Trollope account,” the apostle explains “is to make it clear that manifestations of these kinds of issues have been apparent for a very long period of time and against every faith.” There is thus some very significant analogy to be sought between the questions that concerned the British novelist and our own. But just what are “these kinds of issues”? It may seem strange to compare criticisms of the Restored Church in 2020 by advocates of social justice and racial equality with controversies surrounding properties held by the established Church of England in the middle of the nineteenth century. But it is precisely the dissimilarity on many apparently important points that invites us to adopt a “more distant perspective” that allows us to consider the broadest and deepest features that our situation might share with Trollope’s. A brief consideration of certain features of the novel in question can, I think, clarify what “these kinds of issues” are, and so what Elder Cook would have us learn from Anthony Trollope.

Clearly neither Trollope’s nor Elder Cook’s sympathies are with the reformer Dr. Bold, whose reforming zeal is said to partake of the imprudent and destructive revolutionary spirit of the French Jacobins (the most radical faction in the French Revolution). “Fiat justitia , ruat cœlum” (Justice be done, though the heavens fall), is the motto by which this character reassures himself. Bold reform tends to take it for granted that old customs are evil and “change” is inevitably good; it is thus often blind to the goods represented in institutions and practices that we tend to take for granted. Bold’s righteous campaign, mobilized through the new mass media of the day, the newspaper, is shown to be driven by an irresponsible intellectual vanity, a self-image informed by abstract notions of justice and oblivious to concrete goods and interests embodied in the actual situation of the warden and his little hospital.

We have seen that the warden, a good and sincere, if heretofore somewhat comfortable and complacent Christian, is far from immune to Dr. Bold’s claims. In fact the main arc of Trollope’s story is defined by Septimus Harding’s ‘bout of Christianity’ — the delicacy or fragility of what he understands to be his Christian conscience —which in effect causes him to grant moral superiority to Dr. Bold’s rash and revolutionary idea of reform. What are we Christian readers to make of the warden’s supposedly Christian conscience? While, like Elder Cook, we must surely admire the warden’s meekness and humility, his willingness to consider the claims of equal justice, even when his own substantial interests are at stake. Yet Trollope clearly does not encourage the reader to endorse Harding’s rather hasty and partial interpretation of his Christian duty:

Opinion was much divided as to the propriety of Mr Harding’s conduct. The mercantile part of the community, the mayor and corporation, and council, also most of the ladies, were loud in his praise. Nothing could be more noble, nothing more generous, nothing more upright. But the gentry were of a different way of thinking—especially the lawyers and the clergymen. They said such conduct was very weak and undignified; that Mr Harding evinced a lamentable want of esprit de corps, as well as courage; and that such an abdication must do much harm, and could do but little good (Kindle 2690).

Trollope’s lack of enthusiasm for Mr. Harding’s character is further clarified from two additional elements of the story. First, the warden’s “conscience” is very heavily influenced by a self-consciousness of his reputation as portrayed in the newspapers and in the gossip of those influenced by them. He simply cannot bear the shame of being considered unworthy by the leading organs of public opinion. Second, and decisively, the warden’s “sacrifice” of his worldly goods is shown to be irresponsible and ultimately self-serving. Because of his social standing and connections, when the dust has settled from his abandonment of his property and office, Septimus Harding retains a comfortable material existence and social standing after all. The same can be said of Dr. Bold who, having achieved a kind of moral celebrity through his brilliant pursuit of social justice, marries the warden’s daughter and settles comfortably into the conventional community, reconciled with the church establishment—a “tenured radical,” we might say, before its time. But what is most decisive in the implicit but clear moral judgment of the novel is that life turns out to be much worse in the absence of attachment between the warden’s property and his calling as a Christian servant of the old men of the hospital. The beautiful property goes to seed, and the old men are abandoned, left largely without care and without love – e.g., “six have died, with no kind friend to solace their last moments, with no wealthy neighbour to administer comforts and ease the stings of death” (Kindle 2795, 2799).

The world has been made worse by Bold’s finally cheap and abstract “justice” and by Harding’s deference to it.

Listening to Elder Cook’s speech against the background of Trollope’s study of the problem of Christian conscience in The Warden illuminates the question of the proper stance of Christians and Christian institutions in the face of today’s social and ideological upheaval. Adopting the distant perspective of a long past confrontation between fashionable reform and concrete, responsible Christian service, we can discern more clearly how we should today, as Elder Cook counsels, “support peaceful efforts to overcome racial and social injustice.” His concern, he then makes plain:

Is that some are also trying to undermine the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights that have blessed this country and protected people of all faiths. We need to protect religious freedom. Far too many have turned from the worship of and accountability to God. This has its roots, at least in part, in the academic world. (my emphasis).

Finally, Elder Cook makes perfectly clear the essential point of his long historical perspective and of his comparison with Trollope’s The Warden when he quotes from “Daniel Schwammenthal, a prominent European Jewish leader.”

America can’t remain the leader of the free world . . . if the country goes beyond acknowledging that racism and inequality persist and must be fought, and instead convinces itself that it’s inherently and irredeemably racist. . . .

Yes, the U.S. has not always lived up to its ideals. But to claim that the Founding’s “promissory note” was never anything but a scam to maintain a system of white oppression is ahistorical revisionism that will erode the country’s foundation.

The analogy appears clear between a strong tendency today to understand ourselves as “inherently and irredeemably racist” and warden Septimus Harding’s unfortunate interpretation and application of his “bout of Christianity.” A church, as much as a country, must lift from where it stands, with full awareness of the blessings and responsibilities it has been given, and of their concrete, practical implications. To flee from these concrete duties and attachments in pursuit of the popular and academic prestige of some abstract and elusive idea of “social justice” would be to abandon our moral inheritance, and with it any ground on which we might stand in seeking truly to improve the lives and the character of our neighbors and fellow saints and citizens.

It is notable that no character in Trollope’s novel represents the right approach to the challenge of reform. Dr. Bold, the reformer, is imprudent and drunk on an abstract idea of righteousness. The higher church leaders are typical reactionaries who will hear nothing of any institutional imperfections in the established church. And the warden himself misinterprets Christian humility in a way that makes him vulnerable to the moral posturing of the reformer and unable to defend his proper responsibilities.