Riots at our nation’s Capitol. Violent protests in our streets. Recent headlines do not lack images of conflict and violence in our society. Personally, I don’t envision Jesus going to Kenosha, Wisconsin, with an AR-15. For those who might imagine otherwise, the authors of the new book Proclaim Peace: The Restoration’s Answer to an Age of Conflict, have a message for a world where violence is often seen as the right or the only response. The book’s introduction begins with Christ as its central focus, proposing that “peacebuilding is at the heart of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ,” and that the pursuit of peace “is nothing more nor less than truly worshiping and following ‘the founder of peace,’ Jesus Christ.”

As the authors note, Proclaim Peace is far from the only message of this sort. Many have written on religiously motivated theories of nonviolence based on Christian ideals, and the book liberally cites figures like Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela, and a number of other authors who have written about peacebuilding both in Christian and other faith traditions. But this book is the first to bring together a comprehensive view of the theology of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—or “restoration” theology—as an addition to this impressive cadre of peacemaking texts. The title of the book is based on a verse in the Doctrine and Covenants, which reads “Renounce war and proclaim peace.” The authors propose that the unique theology of the restored Church offers “effective strategies to mitigate violence and transform conflict,” yet to be fully explored by those inside and outside the Church—with their own book offering a great start to this conversation.

The addition of Proclaim Peace to the larger peacebuilding conversation is significant. Many years ago, as I was finishing a master’s degree in alternative dispute resolution at Pepperdine, I chose to write my capstone project on a proposed mediation program for the Church. As part of this project, I did extensive research in an attempt to provide a basis for the principles of dispute resolution in Church theology. While the doctrine was certainly there, both as evidenced in Church history and some helpful commentary from Church leaders scattered throughout conference talks, I could find no analysis—academic or otherwise—that provided a comprehensive review of peace principles from the perspective of the restored gospel. Rather, many of the sources for my capstone were found in texts from other Christian faiths, the most notable being materials from Ken Sande and Gary Friesen under the appellation “Peacemaker Ministries,” a nondenominational Christian group organized to “assist Christian churches to respond to conflict biblically.”

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints should not be absent from this conversation. With the release of Proclaim Peace, Patrick Mason and David Pulsipher have added a new voice on this subject with a broad and insightful overview of restoration theology as it relates to nonviolence and peacebuilding. And these are not just any voices. Mason is an expert in Latter-day Saint history and culture at Utah State University, and Pulsipher, a practicing mediator who leads a program in peace and conflict transformation at BYU-Idaho. The book leaves us with a hopeful message that conflict can be transformed in a way that can help us achieve a Zion society.

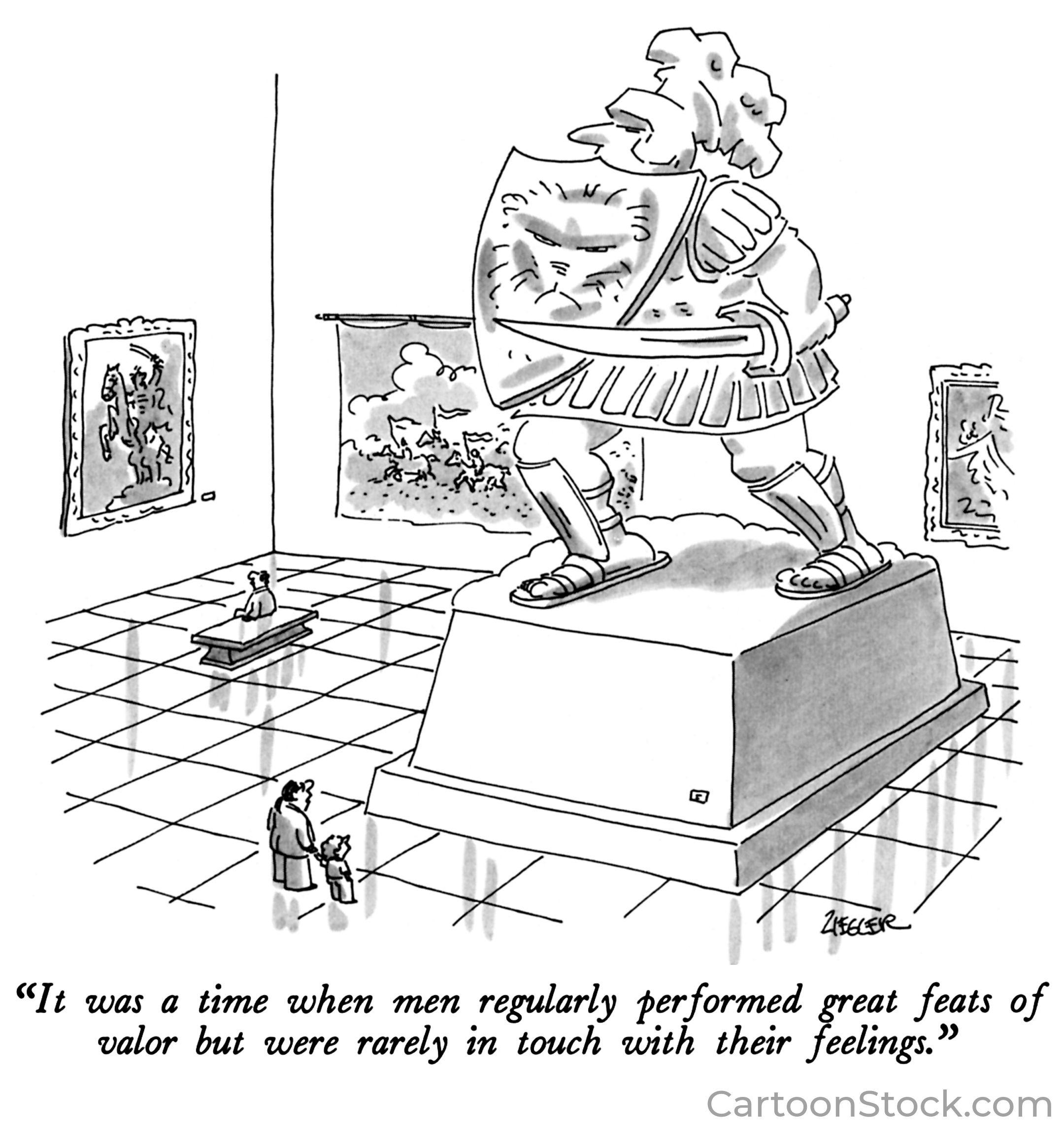

That theory of power and influence is discussed early in the book, where they posit that not only priesthood power, but “no power or influence can or ought to be maintained … only by persuasion, by long-suffering, by gentleness and meekness, and by love unfeigned” (emphasis mine). From this vantage point, violence or force can only ever work as a temporary means of maintaining power. Pointing to many examples in the Book of Mormon, the authors note that societies have two choices: the word or the sword. The sword can only exert power in the short term, and in every instance, ultimately brings about destruction.

Through Jesus’s life and atonement, we see a perfect example of the ethic of “love unfeigned” and nonviolence. The book emphasizes that the salvation of Christ is both individual and communal. The atonement has the power to redeem both individuals and societies, and “redemption is not merely an individual affair.” As such, the book compares and contrasts different instances in the Book of Mormon and Church history where groups or societies reacted to provocation with either violence or nonviolence. In doing so, the book deals fairly well with the thorny issues of whether violence is ever justified and the conundrum of divine violence— instances in scripture where it appears that God allows or even commands or causes violence— ultimately concluding that, while violence may, in limited circumstances, be considered “justified,” the nonviolent path is the only way for us to be truly “sanctified,” and the only response that leads to lasting peace.

In the end, the book leaves us with a hopeful message that conflict can be transformed in a way that can help us achieve a Zion society, not just in some future millennial state, but in the here and now. These were by far my favorite parts of the book. For instance, they write: “Restoration theology does not equate conflict with violence. Violence is a destructive form of conflict, but not all conflict is destructive. Rather, many if not most forms of conflict are potentially creative, even beautiful and necessary, because conflict is divinely ordained.”

This distinction between destructive and creative forms of conflict is significant. When I teach conflict resolution, I always lead my students through a thought exercise where I ask them to consider a world with zero conflict, no differences, and no disagreements. Almost without exception, my students conclude that this is not the world they want. This is because, as is echoed in the book, conflict allows us the opportunity to learn, grow, and change. Moreover, every conflict presents us with a choice of how we will respond. As they write, “Conflict is inevitable in human relationships. … Our choices [of how to engage that conflict] will determine whether the conflict will tend toward a creative or destructive dynamic. … When we act creatively, however haltingly or imperfectly or mixed with other motives, we open the possibility that our conflict might ultimately become constructive.”

As reflected here, God created a world of dualities and “opposition in all things.” It is even through these dualities that the world was created: light and darkness, land and water, male and female. As the book notes, “conflict is a necessary aspect of our existence to be embraced and harnessed for its creative capacities rather than avoided or vilified.” As such, “one of the tasks of would-be peacebuilders is to learn to harness conflict’s creative capacities while also transforming its more destructive forms into conditions in which humans can live together in peace and justice.”

Ultimately, this is the basis of a “Zion society,” which does not rest on the absence of difference but on the presence of love. The book maintains that, in societies, violence is not just individual but can also be structural. One key aspect of Zion communities in the Bible and Book of Mormon was the absence of social or economic division or inequality, with it often being noted that there were “no poor among them.” The authors state that structural or cultural elements within societies that exacerbate inequality can create structural violence which can inhibit or prevent individuals and societies from attaining their full potential. The book calls on members of the Church everywhere to “proclaim peace” by broadening our view of all forms of violence, including those that exist within the culture or structures of society, and then to be “anxiously engaged in [the] good cause” of peacebuilding in our communities.

The book does exhibit some notable omissions: there is little mention of Jesus using force to cleanse the temple or the early Saints’ failed attempts at using the United Order in their efforts to build a Zion society. However, any omissions are fairly minor both because of the comprehensiveness of what is included and because, as the authors admit, this is just a beginning to the conversation.

It is an auspicious beginning at that. With Proclaim Peace, Mason and Pulsipher have truly encouraged Latter-day Saints to “claim a seat at the peacebuilding table,” by showing how the unique teaching of restoration theology can add to the ongoing conversation. More than that, they have provided a jumping-off point for faithful members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who are interested in the larger work of peacebuilding. Inasmuch as we have all been commanded to “proclaim peace,” shouldn’t we all be interested? Indeed, as they say, “[w]e can be peacebuilders not in addition to being members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but rather because we are Latter-day Saints who belong to the Church of Jesus Christ.” Proclaim Peace provides a roadmap to how to pursue this work in a deeper and theologically consistent way.