I begin with a story. When our youngest son Jared was about nine years old, he was in the back seat with his brothers while Julie and I drove down the road from Oak Hills in Provo that goes along the north side of the Provo temple. The view of the valley is quite commanding there. As we looked out of the expanse of Utah County and of Utah Lake and the mountains to the West, the sky was very dramatic, with great contrasts of light and darkness and displaying various shades of red and purple. Jared was clearly impressed. He sat upright to have a better look and exclaimed: “Holy cow! Don’t tell me it’s the Second Coming!” He then added, with hardly a pause, out of concern for our neighbors to whom he delivered daily newspapers: “I feel bad for those people who paid ahead on their subscriptions!”

For us Latter-day Saints, our view of politics and of public affairs more broadly may depend significantly on how we situate ourselves eschatologically, that is, in relation to the “Last Things” prophesied in scripture. Especially when politics is increasingly divisive, confusing, and unpleasant, it is comforting to remember that the world is ultimately in God’s hands and that it is not up to us to decide the final outcome. Politics Matter.

For behold, it is not meet that I should command in all things; for he that is compelled in all things, the same is a slothful and not a wise servant; wherefore he receiveth no reward.

“Verily I say, men should be anxiously engaged in a good cause and do many things of their own free will, and bring to pass much righteousness;

“For the power is in them, wherein they are agents unto themselves. And inasmuch as men do good they shall in nowise lose their reward.

“But he that doeth not anything until he is commanded, and receiveth a commandment with doubtful heart and keepeth it with slothfulness, the same is damned” (D&C 58:26-29).

Until we are told we can stop living providently and exercising foresight—or stop paying our newspaper subscription a month in advance—we remain agents responsible for making the best future we can for ourselves and our communities. Keeping in mind both our ultimate dependence on Higher Powers for what matters most and our moral responsibility to do what good and to prevent what evil we can, let us consider these two religious statements concerning politics:

The Manhattan Declaration: A Call of Christian Conscience (2009; excerpt)

… freedom of religion and the rights of conscience are gravely jeopardized by those who would use the instruments of coercion to compel persons of faith to compromise their deepest convictions. … we affirm 2) marriage as a conjugal union of man and woman, ordained by God from the creation, and historically understood by believers and non-believers alike, to be the most basic institution in society … We pledge to each other, and to our fellow believers, that no power on earth, be it cultural or political, will intimidate us into silence or acquiescence. It is our duty to proclaim the Gospel of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ in its fullness, both in season and out of season. …

LDS Statement on Neutrality (excerpt)

The work of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints includes sharing the gospel of Jesus Christ, strengthening individuals and families, and caring for those in need. The Church does not seek to elect government officials, support or oppose political parties, or, generally, take sides in global conflicts. The Church is neutral in matters of politics within or between the world’s many nations, lands, and peoples. However, as an institution, it reserves the right to address issues it believes have significant moral consequences or that directly affect the mission, teachings, or operations of the Church.

The Manhattan Declaration is a straightforward argument for the importance of religious truth in political life. The Latter-day Saint statement on neutrality expresses a desire to keep the church out of politics as much as possible. The question, of course, is just how far such a neutral stance is indeed possible. The exception to the posture of neutrality enters in immediately as soon as “significant moral consequences” are at stake. We are led to ask, then, whether moral questions can, for the most part, be kept separate from political questions. Lower the temperature of politically related debate in our own congregations.

Political theorist Scott Yenor has insightfully articulated the current state of social norms on sexual morality:

Every country has a sexual constitution: a set of laws and opinions, which use shame and honor to shape and guide sexuality…. We currently live under the Queer Constitution, which claims to—and in fact does—reject the Straight Constitution. …It moved from gay rights in the 1970s to proclaiming “Gay Pride” a virtue in the 1990s, … to constitutionalizing same-sex marriage in the 2010s, to protecting gender identity under the civil rights laws in the 2020s, to practically banning intellectual and legal opposition to the Queer Constitution on speech platforms. …The live-and-let-live attitude, hoped for by conservatives and promised by revolutionaries, cannot, in principle, hold. Indeed, the move from legal tolerance to public celebration is perfectly logical.

It’s hard to disagree with Yenor’s diagnosis. When society is arrayed in such plain and overt opposition to the teachings of the Church, the question of neutrality takes on a new significance. To what extent should we or can we be neutral?

“Fairness,” “Tolerance,” and the Common Good

We hope to avoid bitter public conflict over such sensitive moral issues by organizing political life in terms of an idea of “fairness” rather than with reference to a substantive moral agreement. “Fairness” is a pragmatic substitute for moral agreement. But can “fairness” be defined apart from some broadly shared understanding of the common good, of our common purposes? And can our understanding of the common good be severed entirely from the philosophical and religious questions of human nature and the human good? Can we define “human rights” apart from some substantive understanding of human decency and human flourishing? The attack on moral truth is never done.

“There is hardly any human action, however private it may be, which does not result from some very general conception men have of God, of His relations with the human race, of the nature of their soul, and of their duties to their fellows. Nothing can prevent such ideas from being the common spring from which all else originates.”

If Tocqueville is right (and I think he is), then the concept of “fairness” will not save us from hard questions about how we understand the common good—about our nation’s “sexual constitution” and its moral constitution more generally. Elder D. Todd Christofferson has explained very clearly why morality is not a purely private or purely religious (as distinct from more widely social) concern:

The societies in which many of us live have for more than a generation failed to foster moral discipline. They have taught that truth is relative and that everyone decides for himself or herself what is right. Concepts such as sin and wrong have been condemned as “value judgments.” As the Lord describes it, “Every man walketh in his own way, and after the image of his own god” (D&C 1:16). As a consequence, self-discipline has eroded, and societies are left to try to maintain order and civility by compulsion. The lack of internal control by individuals breeds external control by governments.

“Tolerance,” like “fairness,” may seem to offer an easier, less burdensome alternative to our public responsibility for a wholesome understanding of human nature and human purposes. But, as PresidentDallin H. Oaks has explained, citing President Boyd K. Packer, “The word tolerance does not stand alone. It requires an object and a response to qualify it as a virtue . . . Tolerance is often demanded but seldom returned. Beware of the word tolerance. It is a very unstable virtue.”

Tolerance is unstable and often, in fact, duplicitous, I would say, because our view of the scope of tolerance—the range of behaviors and policies deserving of acceptance—always depends upon some more substantive moral convictions. “Tolerance” is often wielded as a weapon against more traditional moral viewpoints, but the morality—and the view of humanity—behind the deployment of “tolerance” is never itself question. All too often, tolerance is meant to apply to my opinions and practices but not to yours.

“Neutrality”: Context and Limits

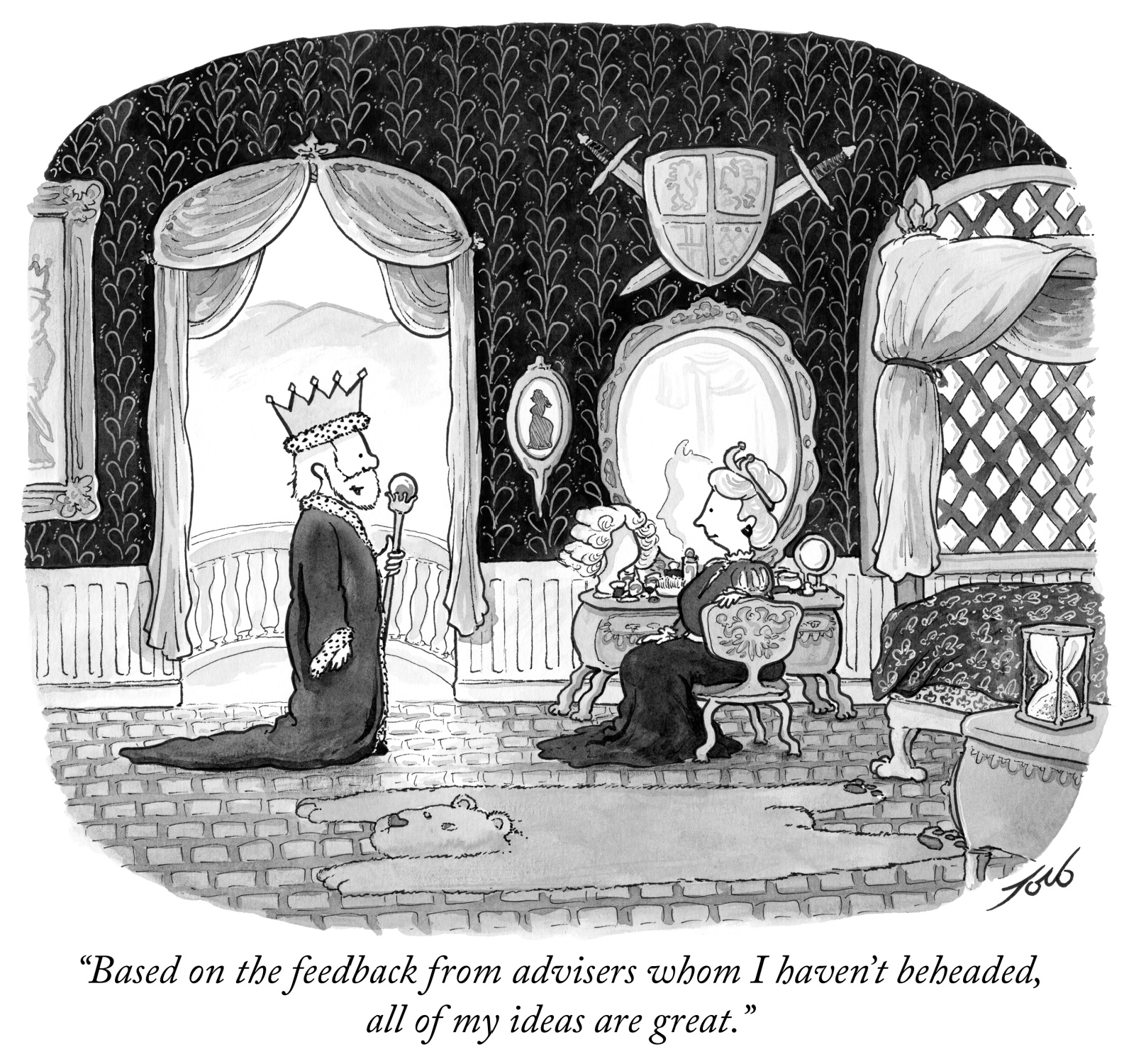

How, then, are we to understand the Church’s emphasis on political neutrality, fairness, and tolerance, and apparent disinclination in the present political and social context to take a strong public stand on matters of substantive morality such as is expressed in the Manhattan Declaration?

To begin to explore this question, it is important to see that while these teachings are in part explicitly grounded in the fundamental Christian virtue of charity or love, it is also reasonable to postulate that they are intended to address current political and social circumstances of the Church in North America in a practical way. It is natural and right that the Church should attend first and foremost to its own interests—that is, to its divine mission of saving souls—of showing the way to Eternal Life to the living and of binding together the generations and redeeming the dead through temple ordinances. In a time of the weakening of shared moral and social norms and of increasing ideological extremism, the Church’s first political priority must be to secure its right to pursue its religious purposes. Implicit in the background of such practical political judgments is, of course, the question raised by my son’s apocalyptic response to a dramatic skyscape: just what time frame are we working with here? Are longer-term political considerations (our concern for a sound shared morality adequate to support a self-governing society) to be devalued in view of the imperatives of the last days?

However much weight we give to such millennialist considerations, we can understand why Latter-day Saint involvement in public debates, such as the lost battle against the redefinition of marriage to include homosexual couples, has, at least for now, apparently, been sacrificed to a rhetoric of morally “neutral” fairness and tolerance with a view to securing in exchange a general recognition of rights of religious free exercise. Rather than hoping to contribute to the common good of society by participating in public debates over issues of fundamental social morality, we hope, at least for a time, for example, to be allowed to continue employment practices in Church education which many now would hope to abolish as “discriminatory,” not to mention to continue to uphold norms in our temple ceremonies that increasingly violate the deepest moral or ideological sensibilities of a powerful block of public opinion, especially elite opinion. While there will always be costs as well as benefits to such rhetorical and political choices, it is not difficult to imagine a reading of our current political and social circumstances that would explain and justify the now dominant posture of “neutrality” or “fairness for all.”

Whose Neutrality? The Church and its Members

That said, it is important to recognize that the Church’s stated and official policy applies to the Church as an institution and is not being advanced as the one true political stance to be adopted by the general membership. It is not clear, moreover, that the public-relations posture that dominates church communications is the best stance for all of its members to take in their public engagements. And, speaking of the membership, another important motive in the Church’s messaging regarding politics seems to be a determination to lower the temperature of politically related debate in our own congregations. It is possible to acknowledge the importance of responsible engagement by Latter-day Saints in the difficult issues that roil our public life while seeing that it is a high priority to preserve peace and brotherhood among ourselves. This is certainly an important purpose in President Russell M. Nelson’s very forthright call, echoed by other Church leaders, for us all to be “peacemakers”:

You have your agency to choose contention or reconciliation. I urge you to choose to be peacemakers, now and always.

Anger never persuades. Hostility builds no one. Contention never leads to inspired solutions. Regrettably, we sometimes see contentious behavior even within our own ranks.

Now, I am not talking about “peace at any price.” I am talking about treating others in ways that are consistent with keeping the covenant you make when you partake of the sacrament. You covenant to always remember the Savior. In situations that are highly charged and filled with contention, I invite you to remember Jesus Christ. Pray to have the courage and wisdom to say or do what He would. As we follow the Prince of Peace, we will become His peacemakers.

President Nelson then interjected, as many will recall, the genial observation that “At this point, you may be thinking that this message would really help someone you know.” And, of course, the tendency to weaponize even the idea of peace-making is a very real problem. As President Packer once said of tolerance, “peace-making” can perhaps also be an “unstable virtue.” Everyone wants peace on his or her own terms, especially when he is not even aware that he is setting terms. Thus President Nelson’s apparently casual aside is, in fact, very significant: “I am not talking about ‘peace at any price.’”

The Big Exception

Having outlined a number of ways to explain and validate the Church’s posture of political neutrality, it is time to notice the massive exception that accompanies the neutrality statement, an exception that might well prove to be more important than the rule: The Church “reserves the right to address issues it believes have significant moral consequences or that directly affect the mission, teachings or operations of the Church.” Of course, what counts as “significant moral consequences” or as directly affecting religious mission is a question open to interpretation, to say the least. As Elder Oaks has himself argued with some force, all legal questions—and I would add, at some level, all political questions—are finally moral questions. Despite the too common nostrum against “legislating morality,” we, in fact, never legislate anything else—or how can we claim that it is morally right to obey and morally wrong to disobey the law? Politics is not a debating society.

Much would seem to depend, then, on the Church’s interpretation of “significant moral consequences,” which obviously would require a highly contextualized judgment. Just to cite the most obvious and troublesome example: is public policy regarding abortion morally “significant”? It certainly would seem so. But can the Church, in its official capacity, make a significant, constructive difference in determining such policy? And if so, how? And it certainly can be argued that there are circumstances in which it may actually be more advantageous, in terms of the Church’s essential mission, for it to remain “neutral,” or perhaps simply silent, even where matters of fundamental moral importance are at stake. The moral issue may be simple for us Latter-day Saints, but the surrounding political questions, including a realistic assessment of actual risks, opportunities, and constraints, are more complex.

Our Pragmatic Situation

Having recognized that the Church’s political stance must depend on the specific political circumstances in which it chooses to intervene, let us consider briefly what are the most fundamental constraints that the Church and its members now confront as we face outward toward the political world in the United States. A simple way of characterizing our political situation as a religion today might be simply to acknowledge (1) that there once was a culture war that defined much of political debate in the United States, (2) that the Church not long ago made certain efforts to intervene in that “war” (contributions to the defeat of the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s; the Family Proclamation itself, 1995; mobilization in favor of Proposition 8 in California to prevent the radical redefinition of marriage. 2008), but (3) that now the moment of the culture war is over, not because the cause was not important or that our efforts were not legitimate, but simply because we have lost.

Is this characterization of our situation adequate? There is no question our circumstances are fundamentally different than just a decade ago, and there is no point intervening as if the year were 1995 or 2008. On the other hand, we delude ourselves if we imagine that, just because we have lost a certain fundamental battle, the war is, therefore, over. Because the plain fact is we can keep losing—at least if Yenor (see above) is in any way right about the ascendant “sexual constitution” that now governs us. The attack on moral Truth, or simply basic truths about human nature, male and female, is never done. Tolerance or “respect for differences” is a very unstable virtue indeed, and the demand for “equality” (or, now, “equity”) is an inherently bottomless demand.

Here is what Pierre Manent, the French political philosopher, wrote in response to the radical redefinition of marriage in his own country:

The demand for the right to marriage on behalf of … [homosexual] couples must be considered a metaphysical demand, that is, a demand that bears on the meaning and the whole of human life … Insofar as marriage was the crucial institution of a human world organized according to natural law, the law of which we are speaking aims to overturn or abolish this very order. Henceforth societies living under this law are involved in an experiment that is equally crucial and whose consequences yet to come, public as well as private, will no doubt be commensurate with the audacity or imprudence of what has been done.

This legislation … owes [its] ascendancy to the ambition I have called metaphysical, the claim to inscribe into positive law the thesis according to which the just or legitimate human order excludes all reference to a natural norm or purpose.

The attack on natural norms or purposes cannot be sated, and so there is little ground for hoping that the enemies of truth will be content to enjoy their past victories and adopt a “live and let live” posture towards individuals, families, or churches and other communities that wish to maintain the more traditional norms and practices that are now increasingly seen as “alternative lifestyles.”

Elder Robert D. Hales stated in the October General Conference, 2013, “The world is moving away from the Lord faster and farther than ever before. The adversary has been loosed upon the earth.” Many of the brethren have echoed this assessment of our practical situation. If we accept this assessment, then it is hard to see how we might expect a posture of neutrality or hope of reciprocal “fairness” to offer a long-term solution, or a viable long-term approach, to our political and cultural circumstances as a Church. It is more likely that we will need more of the harder virtue of courage praised by Elder Russell M. Nelson in the April 2014 General Conference (quoting President Thomas S. Monson, 1986): “Of course, we will face fear, experience ridicule, and meet opposition. Let us have the courage to defy the consensus, the courage to stand for principle. Courage, not compromise, brings the smile of God’s approval” (my emphasis).

President Oaks offered an even more bracing assessment of our practical (political and cultural) situation in an address to the BYU-Idaho community in 2015. “The denial of God or the downplaying of His role in human affairs that began in the Renaissance has become pervasive today,” he said. While observing that “the glorifying of human reasoning has had good and bad effects,” President Oaks went on to explain, “prophecies of the last days foretell great opposition to inspired truth and action. Some of these prophecies concern the anti-Christ, and others speak of the great and abominable church.” President Oaks thus associated the core teaching of nothing less than this “great and abominable church,” which “must be something far more pervasive and widespread than a single “church,” as we understand that term today” with Korihor’s teaching of “moral relativism” in the Book of Mormon: “Break free of the old rules. Do what feels good to you. There is no accountability beyond what man’s laws or public disapproval impose on those who are caught.” This is, to say the least, a sobering perspective on our practical circumstances as members in interface with the larger culture and with political and legal powers and principalities.

The Perils of Pragmatism

To the considerable degree that the doctrine of “the anti-Christ” or the “great and abominable Church” increasingly pervades our society, it seems unlikely that anything resembling “neutrality” will be a viable posture for the long term for Latter-day Saints. To be sure, there may be many times when the Church judges it prudent to keep its head down in view of its most important and urgent religious priorities. But it is important that we as members guard against interpreting this prudent or pragmatic posture as a compromise regarding basic principles and eternal truths. It is natural, almost irresistible, as we enter into necessary political compromises that we begin to adapt our understanding of truth and morality to the terms of that compromise. Pragmatism in politics can be a legitimate virtue.

To be sure, “patience, negotiation, and compromise” may be seen not only as means to [political and social] ends but “as social and spiritual ends unto themselves,” as public intellectual Jonathan Rauch recently argued, in praise of what he takes to be Latter-day Saint political theology. There is no doubt that there is something to be learned and real virtues to be refined by earnest and temperate engagement in the great moral debates that now shape American politics. Rauch is certainly right that believers benefit from learning how to check the impulse to “impose my will politically to limit your agency.” At the same time, however—and this is a simple truth Rauch seems to ignore—politics is not a debating society in which the conversation never ends and consequential decisions can be deferred indefinitely. A long-time advocate of same-sex marriage himself, Rauch would appear not to be eager to re-open that debate. Law and policy will be determined one way or another, and individual agency will have to bend to this determination. (For Rauch, the ultimate authority is a purely secular and quasi-scientific “constitution of knowledge” that excludes all religiously tainted convictions.) In any case, moral agency makes no sense without a moral framework, and civil legislation will always partake of and contribute to a shared moral vision. As President Oaks has taught, all law involves the “legislation of morality”—one morality or another. Marriage as we know it has, for public and legal purposes, been radically redefined and essentially compromised in a way that has real consequences for the well-being of Americans.

We may therefore find comfort in the assurance that “Congress has now reaffirmed that our beliefs ‘are due proper respect,’” but it is easy to get swept up in the worldview according to which all views deserve respect—but only because they are equally groundless, that is, because there are no rules and no truths about human, political power. It is one thing prudently to recognize the Church’s limited scope of action in the present political environment. It is quite another to define that environment in the relativistic or liberationist terms of our enemies. It is one thing to honor the commandment to love our enemies. It is quite another to imagine we do not have enemies.

In his most recent General Conference address, Elder Christofferson expounded on the importance of the gathering of Israel and the sealing power of the priesthood. The highest purpose of the sealing power is to bind families together forever. One purpose of the gathering is to make the blessings of this sealing available to the saints; another is to protect the faithful from the wrath that must be poured out on mankind as a natural consequence of disobedience to God’s laws and commandments. “Without the sealings that create eternal families and link generations here and hereafter,” Elder Christofferson taught, “we would be left in eternity with neither root nor branches, neither ancestry nor posterity.” He then described the two types of disobedience that merit God’s wrath:

It is this free-floating, disconnected state of individuals, on the one hand, or connections that defy the marriage and family relations God has ordained, on the other hand, that would frustrate the very purpose of the earth’s creation. Were that to become the norm, it would be tantamount to the earth being smitten with a curse or utterly wasted at the Lord’s coming.

Extreme, relativistic individualism and the perversion of the true idea of marriage and family are ideas and lifestyles that portend nothing less than the devastation of the earth. Whatever practical compromises we find it necessary to make in the political realm, we must not delude ourselves that what is at stake in our understanding of the family and of the purpose and limits of sexual expression is a mere matter of individual taste or inclination, a topic upon which reasonable people can reasonably disagree without some being right and others being profoundly, disastrously mistaken. Nothing less is at stake than the very purpose of creation.

Of course, the outcome of our political efforts is finally in the Lord’s hands. President Russell M. Nelson has prophesied: “In coming days, we will see the greatest manifestations of the Savior’s power that the world has ever seen. Between now and the time He returns . . . He will bestow countless privileges, blessings, and miracles upon the faithful.” This promise must give us great comfort and assurance as we navigate the storms of contemporary society. But our responsibilities to our families, communities, and fellow citizens remain: whatever the scope and limits of our moral agency in the present moral and political world, we must exercise that agency in light of our best understanding of God’s ultimate purposes for his creation.

Pragmatism in politics, including when necessary, a public posture of “neutrality,” can no doubt be a necessary and thus a legitimate virtue. But we must not forget that the virtue of pragmatism can be very unstable.