This past August marked the 400th anniversary since the first African slaves were sold in the Jamestown Colony, the beginning of a slave economy that would eventually spread throughout the southern United States. Remarkably, that Virginia peninsula where American slavery began would also be same the location where it began to end, almost two and a half centuries later during the Civil War. While recognizing the ignominious beginning of slavery in America, it is even more important to remember its end and the providential deliverance of four million African Americans from human bondage.

Old Point Comfort—where slavery began, and where slavery began to end

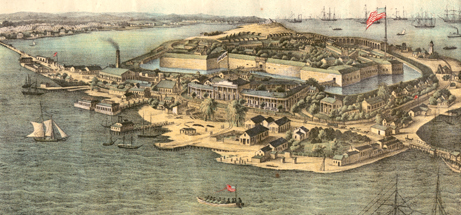

Overlooking the Chesapeake Bay is a strategic peninsula, originally named “Cape Comfort” by Jamestown colonists in 1607, apparently for its good anchorage and the hospitality of the neighboring Kecoughtan Indians. Twelve years after the founding of Jamestown in 1619, and a year before the Pilgrims settled Plymouth, this small Virginia peninsula, “Old Point Comfort,” as it would later be known, was the site of the first marketplace for African slaves in the North American colonies.

In August 1619, the White Lion, an Anglo-Dutch “man-of-war,” set sail for the fledgling Virginia colony after plundering the cargo of the Portuguese São João Bautista, looking to trade the ship’s cargo for fresh supplies from the colonists. John Rolfe, Pocahontas’s widower, recorded that the ship “brought not anything but 20 and odd Negroes,” which the colonists bought “at the best and easiest rate they could.” Captured during tribal conflict in Angola, these men, women, and children who had been bound for hard labor in Veracruz, Mexico, instead became the first African slaves in Virginia.

The peninsula, less than a square mile in size, has long been recognized as a key strategic location for controlling access to the Chesapeake Bay. Just two years after establishing Jamestown, colonists erected a primitive fort there for coastal defense, and various forts were constructed at the site throughout colonial times. As a result of the War of 1812—during which the British controlled the Chesapeake and burnt Washington D.C.—President James Monroe ordered the construction of a massive stone-and-brick citadel. The nation’s best military engineers oversaw its completion, including a young lieutenant named Robert E. Lee. Officially named “Fortress Monroe,” it was nicknamed the “Gibraltar of the Chesapeake Bay,” the largest stone fort ever built in the United States, and one of the few military strongholds that remained under the federal government’s control at the outbreak of the Civil War. To the thousands of Virginia slaves who sought refuge there during the war, it would become “Freedom’s Fortress.”

Contraband of war

In the weeks since the outbreak of the Civil War, the North had rallied around popular opinion for saving the Union, not divisive aims for abolishing slavery. President Abraham Lincoln had emphatically avowed, in his First Inaugural Address, “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists.” And at Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens, federal garrisons had previously returned fugitive slaves to their masters. It was, after all, what the law required at the time. Article Four of the Constitution specified that fugitive slaves “shall be delivered up” to their masters, and the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act enforced that constitutional provision by subjecting law enforcement officials to fines for failing to arrest suspected fugitives.

Butler recognized the military necessity of confiscating “property” that might be used against the United States.

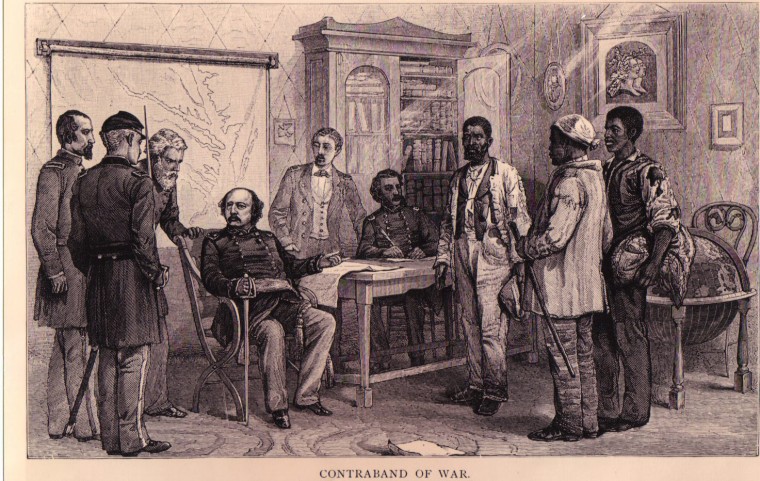

So when Major John Baytop Cary of the Virginia militia rode by horseback the next day to Fortress Monroe and petitioned the Union garrison for the return of the three fugitive slaves, it was by no means a surprising request. What was unexpected, however, was the response from Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler, the clever, self-assured Yankee lawyer-politician-general who commanded the fort. (Butler’s successful law practice led to a political career as a prominent Massachusetts Democrat, which in turn was a springboard for his general’s commission, since Lincoln sought to avoid having the conflict branded a “Republican war” and promoted several reliably Unionist Democrats to high rank.) The general’s answer reverberated throughout the North and, quite literally, changed the course of the war.

Cary: “I am informed that three negroes belonging to Colonel Mallory have escaped within your lines. I am Colonel Mallory’s agent and have charge of his property. What do you mean to do with those negroes?”

Butler: “I intend to hold them.”

Cary: “Do you mean, then, to set aside your constitutional obligation to return them?”

Butler: “I mean to take Virginia at her word, as declared in the ordinance of secession passed yesterday. I am under no constitutional obligations to a foreign country, which Virginia now claims to be.”

Cary: “But you say we cannot secede, and so you cannot consistently detain the negroes.”

Butler: “But you say you have seceded, so you cannot consistently claim them. I shall hold these negroes as contraband of war, since they are engaged in the construction of your [artillery] battery and are claimed as your property. The question is simply whether they shall be used for or against the Government of the United States. Yet, though I greatly need the labor which has providentially come to my hands, if Colonel Mallory will come into the fort and take the oath of allegiance to the United States, he shall have his negroes, and I will endeavor to hire them from him.”

“It was thrust upon me to decide what must be done then and there”

Whatever his sympathies against slavery might have been, Butler was no abolitionist. Before the Civil War, Northern Democrats like Butler abhorred what they viewed as abolitionist fanaticism, which, to their way of thinking, espoused an unyielding moral high ground that only antagonized the South and agitated for unthinkable disunion. (The Chicago Times, a Democratic newspaper, had remonstrated: “Let the negroes alone!—let them ALONE! . . . ABOLITION IS DISUNION. It is the ‘vile cause and the most cursed effect.’ It is the Alpha and Omega of our National woes. STRANGLE IT!”)

But the firing upon Fort Sumter had initiated war, and Southerners’ professed right to slave “property” was now being employed to assist hostile Confederate armies. Among a Northern population divided over the question of abolition, a national policy against slavery could not yet be adopted. But soldiers brought face-to-face with runaway slaves had a decision to make. “Fortuitously it was thrust upon me to decide what must be done then and there,” Butler recalled, “and very fortunately a few moments’ thought caused to flash through my mind the plausible answer at least to the question: What will you do?” It was one thing to support the Fugitive Slave Act as a pre-war policy of conciliation to maintain peace with Southern countrymen. It was quite another to enforce it personally by returning the very persons who ran away from building your enemy’s fortifications. Butler concluded that he could not return slaves to the very masters who were busily building artillery batteries with which to bombard his fort. He was not alone in his sentiments.

A revolution in popular thought

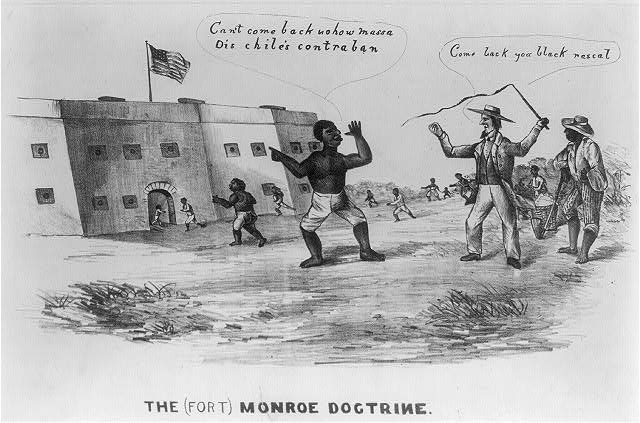

But while first taken as something of a joke—a witty Yankee lawyer getting the best of a cavalierly Confederate officer—the precedent established at Fortress Monroe, and applied initially to just three young men, set in motion the legal basis for the eventual emancipation of millions more. “Out of this incident,” Lincoln’s secretaries John Hay and John Nicolay reflected after the war, “seems to have grown one of the most sudden and important revolutions in popular thought which took place during the whole war.”

In an article for The Atlantic Monthly, Edward L. Pierce explained the subtle, yet revolutionary, transformation that had taken place in the first few months of the war among Northerners hitherto hostile to outright abolitionism:

The venerable gentleman, who wears gold spectacles and reads a conservative daily, prefers confiscation to emancipation. He is reluctant to have slaves declared freemen, but has no objection to their being declared contrabands. His whole nature rises in insurrection when [Henry Ward] Beecher preaches in a sermon that a thing must be done because it is a duty, but he yields gracefully when Butler issues an order commanding it to be done because it is a military necessity. (Edward L. Pierce, “The Contrabands at Fortress Monroe,” The Atlantic Monthly, November 1861, 626–640.)

Pierce was no stranger to the subject matter. A lawyer with degrees from Brown and Harvard, Pierce had enlisted in the Third Massachusetts as a private, and over the summer of 1861, Butler had appointed him to superintend the escaped slaves at Fortress Monroe.

“Every one of them was as much entitled to his freedom as I was to mine”

Word spread quickly among the slave population in Eastern Virginia. W.E.B. Du Bois vividly painted the scene of slaves seeking protection from Union armies:

They came at night, when the flickering camp fires of the blue hosts shone like vast unsteady stars along the black horizon: old men, and thin, with gray and tufted hair; women with frightened eyes, dragging whimpering, hungry children; men and girls, stalwart and gaunt,–a horde of starving vagabonds, homeless, helpless, and pitiable in their dark distress.” (W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Freedmen’s Bureau,” The Atlantic Monthly, March 1901, Vol. 87, No. 519, pages 354–365.)

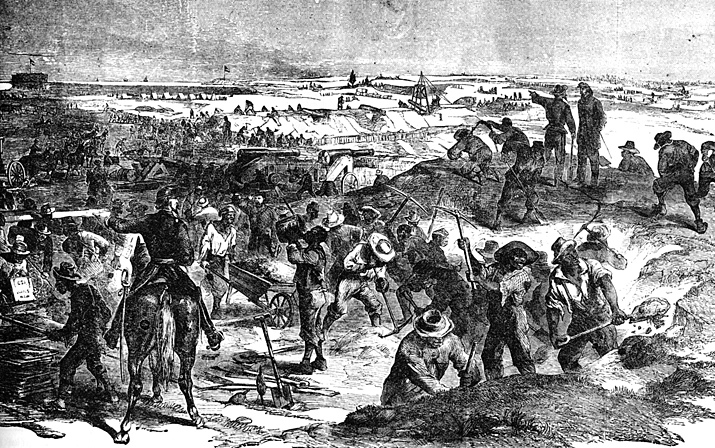

In early July, Butler authorized the employment of the “contrabands,” as they had come to be called, to work on the Union entrenchments. Having been appointed to superintend their labor, Pierce remarked on “the spectacle of a Massachusetts Republican converted into a Virginia slave-master.” Pierce praised their work, complimented their behavior (observing the absence of any “profane or vulgar word,” a compliment which could not be paid to his compatriots in the army), and made “a good report of their industry and morals.” When his three-month enlistment expired, Pierce gathered them together to speak from his heart:

Never before in our history had a Northern man, believing in the divine right of all men to their liberty, had an opportunity to address an audience of sixty-four slaves and say what the Spirit moved him to utter,–and I should have been false to all that is true and sacred, if I had let it pass. I said to them that there was one more word for me to add, and that was, that every one of them was as much entitled to his freedom as I was to mine, and I hoped they would all now secure it. “Believe you, boss,” was the general response, and each one with his rough gravelly hand grasped mine, and with tearful eyes and broken utterances said, “God bless you!” “May we meet in Heaven!” “My name is Jack Allen, don’t forget me!” “Remember me, Kent Anderson!” and so on. No,–I may forget the playfellows of my childhood, my college classmates, my professional associates, my comrades in arms, but I will remember you and your benedictions until I cease to breathe! Farewell, honest hearts, longing to be free! and may the kind Providence which forgets not the sparrow shelter and protect you! (Edward L. Pierce, “The Contrabands at Fortress Monroe,” The Atlantic Monthly, November 1861, 626–640.)

While Pierce’s affection for the contrabands could be expected, given his pre-war antislavery sentiments, the soldiers’ close association with the escaped slaves had even deeply affected General Butler. By the end of July, he wrote to Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, regarding “his” contrabands:

Have they not by their master’s acts, and the state of war, assumed the condition, which we hold to be the normal one, of those made in God’s image? Is not every constitutional, legal, and normal requirement, [both] to the runaway master [and to his] relinquished saves, thus answered? I confess that my own mind is compelled by this reasoning to look upon them as men and women.”

When even a Democrat such as Butler (who, in the most recent presidential primary, had cast his vote for Jefferson Davis—on fifty-seven successive ballots) was ready to recognize Negroes not as property, but as people “made in God’s image,” slavery’s days were numbered. Pierce could not restrain his praise for the general’s letter. Butler, Pierce wrote, “may never win a victor’s laurels on any renowned field, but, [by] depositing [his letter to Cameron] in the archives of the Government, he leaves a record in history which will outlast the traditions of battle or siege.” Over the course of a few months, events in the field of battle were rapidly changing the political calculations of decades.

Contraband, confiscation, and emancipation

Two decades earlier, in 1842, John Quincy Adams, from the floor of the House of Representatives, had declared—“almost prophesying,” wrote Pierce—“that the President, as commander-in-chief, has the authority, as an act of war, to liberate the slaves of the enemy.” Southerners immediately denounced his dramatic enunciation of a “war power” for abolishing slavery. At the outbreak of the Civil War, antislavery advocates recited his argument and urged the North to strike at slavery as a military necessity. While Northern sentiment could not, at that time, agree on liberating all of the slaves of its enemy, it could agree on liberating, at least, the very slaves employed against it. By firing on Fort Sumter, the South inadvertently sowed the seeds that would lead to slavery’s effectual and eventual demise. Within a few months of Butler’s “contraband” doctrine, Congress passed the first Confiscation Act, authorizing Union forces to seize and free any slaves forced to fight or labor directly in behalf of Confederate forces. Almost as soon as the ink dried, proponents of confiscation sought to expand it even farther. In his article for The Atlantic Monthly, Pierce laid out a compelling case for doing so:

The one slave who carries his master’s knapsack on a march contributes far less to the efficiency of the Rebel army than the one hundred slaves who hoe corn on his plantation with which to replenish its commissariat. We have not yet emerged from the fine-drawn distinctions of peaceful times. We may imprison or slaughter a Rebel, but we may not unloose his hold on a person he has claimed as a slave. We may seize all his other property without question, lands, houses, cattle, jewels; but his asserted property in man is more sacred than the gold which overlay the Ark of the Covenant, and we may not profane it. This reverence for things assumed to be sacred, which are not so, cannot long continue. (Edward L. Pierce, “The Contrabands at Fortress Monroe,” The Atlantic Monthly, November 1861, 626–640.)

While the role of mortal ingenuity cannot be denied, others bore witness to more powerful forces shaping the Republic’s response to its most existential crisis.

And it did not. Bloody battles in the first year of the war—Bull Run, Shiloh, Seven Pines, Gaines’ Mill, Malvern Hill—swayed Northern opinion to support even stronger measures against the South over the summer of 1862. The Second Confiscation Act authorized Union forces to seize all slaves owned by those Southerners “engaged in rebellion.” Then on January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing all slaves within the territory of the Confederacy. (Two years later, the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery throughout the United States.) A war to save the Union had become a war to free the slaves. Lincoln had invoked a scriptural admonition in declaring that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.” Northerners came to believe that the “house” of the Republic would not cease to be divided until slavery was ended.

“O let my people go!”

Major Theodore Winthrop was General Butler’s Yale-educated aide-de-camp. A little more than two weeks after Baker, Townsend, and Mallory’s nighttime escape to Fortress Monroe, Winthrop was killed, while rallying troops, in the Battle of Big Bethel, the first pitched land battle of the Civil War. A well-versed writer, with strong antislavery sentiment (he had written his family, “I go to put an end to slavery”), Winthrop understood where Butler’s “contraband” doctrine would lead. In his notebook, he penned a line from Horace in Latin Solvuntur risu tabulae (“The case is dismissed amid laughter”), and then followed in English with his own formulation: “An epigram abolished slavery in the United States.” (An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement.)

While the role of mortal ingenuity cannot be denied, others bore witness to more powerful forces shaping the Republic’s response to its most existential crisis.

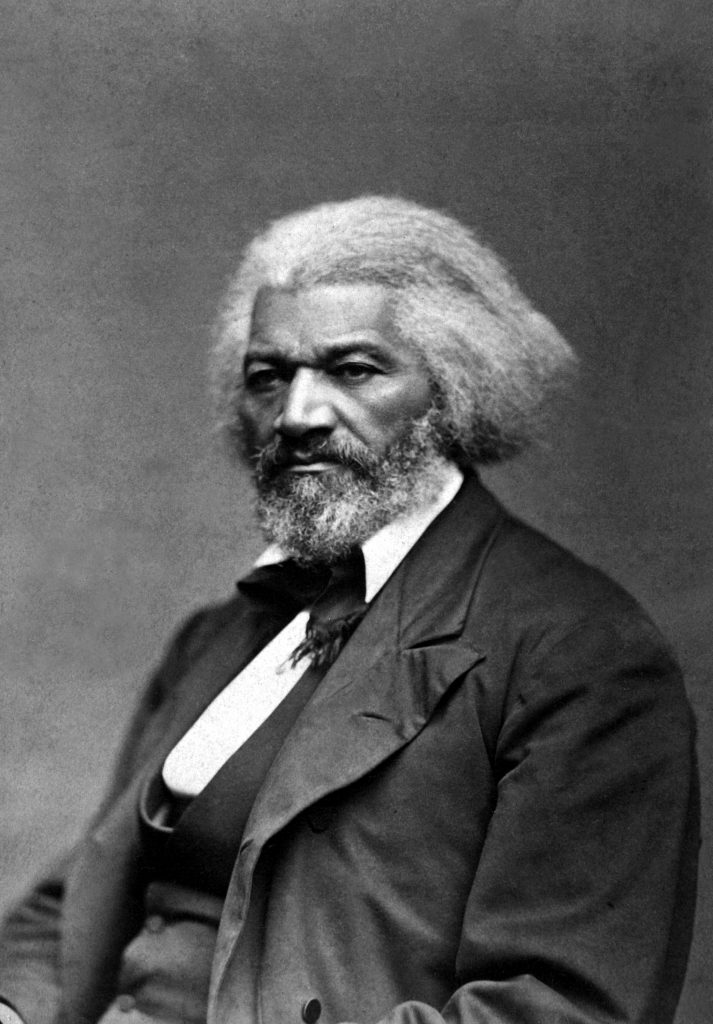

In March 1861, on the eve of the Civil War, Frederick Douglass, the eloquent Negro orator and abolitionist, himself a runaway slave, was ready to give up on the United States. Bitterly disappointed in Lincoln’s promise in the First Inaugural Address not to interfere with slavery where it then existed, Douglass had resolved to set sail for Haiti and make the island of former slaves his home. But in the firing on Fort Sumter and the unified reaction of the North, Douglass felt constrained by indiscernible forces and changed his mind. Lecturing at a church in Syracuse on April 27, just a month before Butler’s decision to free three slaves employed against Union arms, Douglass solemnly pronounced:

Our mornings and evenings have continually oscillated between the dim light of hope, and the gloomy shadow of despair. . . . The thing you and I want, most of all, concerning this mighty strife, is yet far from us. We cannot see the end from the beginning. Our profoundest calculations may prove erroneous, our best hopes disappointed, and our worst fears confirmed. We live but today, and the measureless shores of the future are wisely hid from us. And yet we read the face of the sky, and may discern the signs of the times. We know that clouds and darkness, and the sounds of distant thunder, mean rain. So, too, we may observe the fleecy drapery of the moral sky, and draw conclusions as to what may come upon us. There is a general feeling amongst us, that the control of events has been taken out of our hands, that we have fallen into the mighty current of eternal principles—invisible forces—which are shaping and fashioning events as they wish, using us only as instruments to work out their own results in our national destiny. (Frederick Douglass, “Hope and Despair in These Cowardly Times,” April 27, 1861.)

Three years later, in April 1864, with the ranks of the Union armies swelled by 130,000 black soldiers, many recently liberated slaves, Lincoln echoed similar sentiments; he was concluding his explanation for the genesis of the Emancipation Proclamation:

In telling this tale I attempt no compliment to my own sagacity. I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years struggle the nation’s condition is not what either party, or any man devised, or expected. God alone can claim it. Wither it is tending seems plain. If God now wills the removal of a great wrong, and wills also that we of the North as well as you of the South, shall pay fairly for our complicity in that wrong, impartial history will find therein new cause to attest and revere the justice and goodness of God. (Abraham Lincoln, “Letter to Albert G. Hodges,” April 4, 1864.)

Long before Lincoln reached his conclusion about the purpose of the war, the liberated slaves of Fortress Monroe had reached theirs. Writing of the religious sentiments of the contrabands, Pierce wrote:

They said they had prayed for this day, and God had sent Lincoln in answer to their prayers. We used to overhear their family devotions, somewhat loud according to their manner, in which they prayed earnestly for our troops. They built their hopes of freedom on Scriptural examples, regarding the deliverance of Daniel from the lions’ den, and of the Three Children from the furnace, as symbolic of their coming freedom. One said to me, that masters, before they died, by their wills sometimes freed their slaves, and he thought that a type that they should become free. (Edward L. Pierce, “The Contrabands at Fortress Monroe,” The Atlantic Monthly, November 1861, 626–640.)

Virginia’s slaves had long sung spirituals of deliverance and redemption. Under the auspices of the American Missionary Association, Reverend Lewis C. Lockwood arrived at Fortress Monroe about the first of September 1861, ready to serve the burgeoning population of contrabands, now totaling more than a thousand. During the course of his service, he recorded the words of a song he titled, “The Song of the Contrabands.” [Israelites Leaving Egypt] The verses echoed the major events of Exodus, including the Israelites’ toil and bondage, the Passover night, the parting of the Red Sea, and passage into the Promised Land, with its penultimate verse sounding a prayer for freedom, “O let us all from bondage flee, O let my people go! And let us all in Christ be free, O let my people go!”

There, on the shores where American slavery had begun, recently liberated slaves sang the spirituals of their long prayed for deliverance, a testament to the origin of their freedom.