Seeing Critics of the Church with a Pure Love

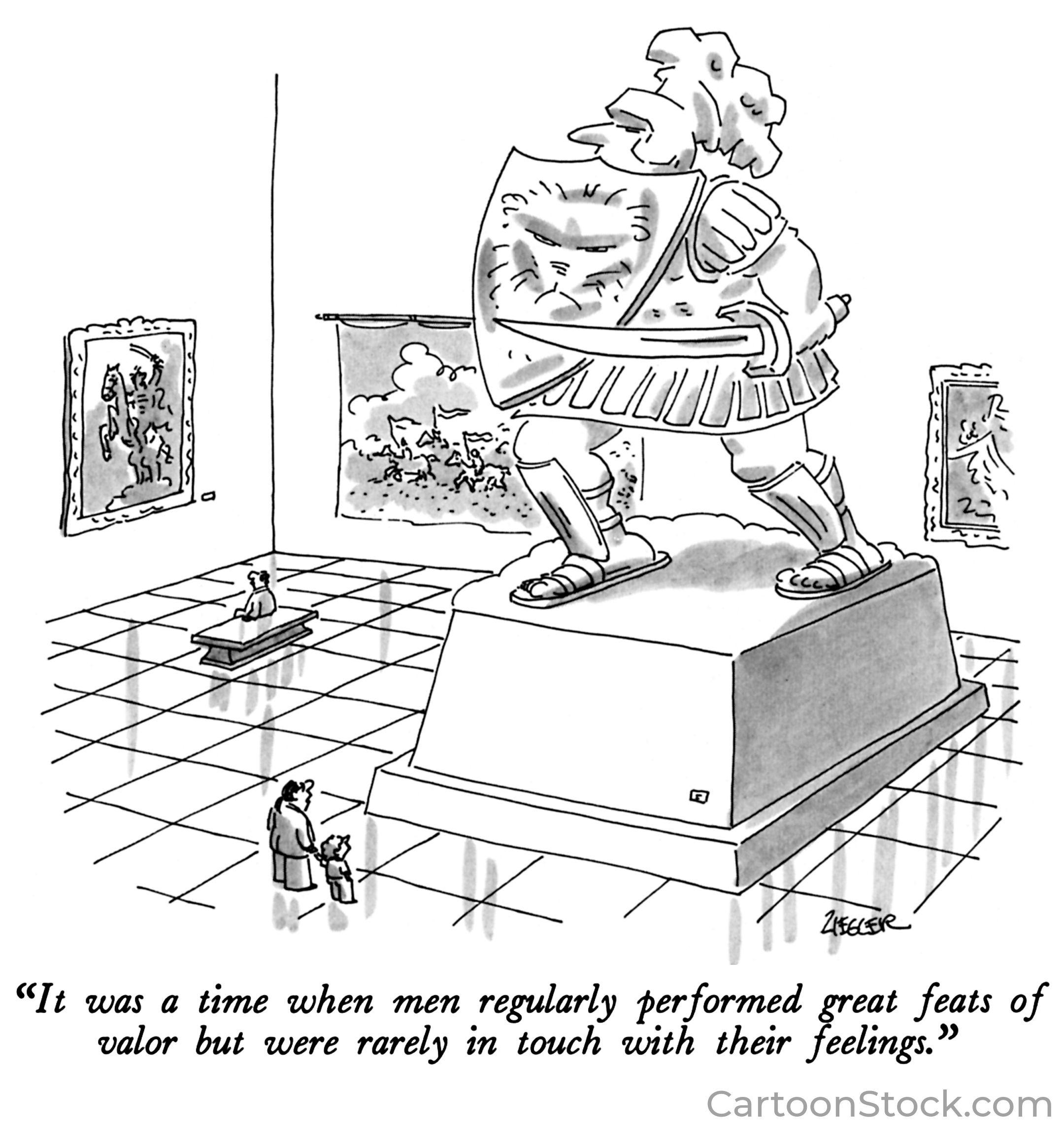

Outside the theater after a performance of the musical “The Book of Mormon,” two young women serving as missionaries laugh with a line of theatergoers who had just spent two hours chuckling at their faith. One man teased them, using a phone recording, fishing for a cringeworthy sound bite. Instead of debating, one sister offered him a copy of the book with a smile: “If you liked the parody, you might like the source.” He took it, still smirking. A week later, he messaged them to say he had read a few chapters and—more surprisingly—he apologized for trying to embarrass them. “I didn’t expect you to be kind,” he wrote. Kindness didn’t convert him (conversion comes by the Spirit), but it converted the moment. That impulse—answer a jab with generosity—has quietly become one of our most reliable instincts.

Our critics (and even our enemies) can refine our courage, our clarity, and our hospitality—charity without capitulation.

We do not concede doctrine, outsource discernment, or grant a heckler’s veto to critics. We listen because people are precious, not because scorn is persuasive, and we keep the “pure love of Christ” as both our motive and method. Learning from our enemies, in this sense, means learning how to love them better. Yes, as necessary, we must answer with facts, with consistency and safeguards; those looking for Jesus Christ and His Church deserve that from us. And when waves of attention build, the posture still holds.

#SurvivingMormonism

The upcoming documentary series “Surviving Mormonism” is generating a fresh crest of negative attention toward The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Another entry in the well-worn exposé genre of Latter-day Saints, the show purports to reveal the “dark history” of the Church through interviews with “abuse survivors, ex-Mormons and former LDS church leaders.” The show will be hosted by reality TV star Heather Gay, whose exodus story from the Church has been published as a New York Times best-seller. We listen because people are precious.

And, if that guess turns out to be true, then part of an appropriate response to such scornful content is to “heed not.” However, engaging in loving and productive ways can also be appropriate, and may provide different benefits.

Many Latter-day Saints online modeled this in a viral response to the show’s title. In a short period of time, many Latter-day Saint creators have used the hashtag #SurvivingMormonism to poke fun at themselves for the often mild annoyances and idiosyncrasies of church members and culture. Examples included: “Surviving Mormonism, but it’s just me carrying a bunch of chairs to impress girls at my ward,” “Surviving Mormonism and it’s just me having to play basketball on carpet,” or “Surviving Mormonism and its High Council Sunday.”

These examples come in the same spirit as the outreach after the offensive Broadway play, which mocked Latter-day Saints and their faith: disarm hostility with humor, neighborliness, and confidence in the gospel rather than defensiveness.

Under normal circumstances, this kind of response softens hearts and builds goodwill. But because Latter-day Saints remain an out-group in many attention markets, these are not normal circumstances, and goodwill is not always reciprocated. The duty remains the same either way: meet caricature with Christlike love without ceding truth.

In the same spirit of not reacting defensively, we can go even further to recognize that every incoming volley is being fired by a human being—a fellow brother or sister in the family of God. The Savior’s example and modern apostolic counsel make clear that accusations and sensationalized personal apostasies sometimes merit our response as directed by the promptings of the Holy Ghost. But when we are called to defend truth, virtue, and the Kingdom of God, we should ensure that we are defending it in the Savior’s way, which means that our responses should always be motivated and shaped by what the Book of Mormon calls “the pure love of Christ.”

Old Bigotries, New Veneers

To understand why this pattern keeps resurfacing, zoom out from one show to the longer storyline. Across two centuries, Americans have recycled the same basic image of Latter‑day Saints with different lighting. In the 19th century, the Saints were cast as a wicked cult—socially alien, politically suspect, theologically off. That caricature licensed extraordinary measures and mob violence. From the mid‑20th century through the early 2010s, the image softened to false religion; good neighbors: Scout troops and service projects, civic leadership, and the 2002 Olympics—the so‑called “Mormon Moment.” For many, the Church read as rigorous but ordinary.

Over roughly the last decade, the mood darkened again—not because the Church pivoted into menace, but because the storytellers and their incentives changed. Prestige docudramas and true‑crime packaging blurred a fundamentalist offshoot into the main body; algorithms prized moral threat; headlines chased sharper edges. The label did the work that the evidence did not. Put simply: the attention markets transformed; the Church didn’t. Americans have recycled the same basic image of Latter‑day Saints with different lighting.

That is why yesterday’s bigotries can return in new veneers. Where 19th‑century broadsheets warned of polygamy and “secret oaths,” today’s packages spotlight weird underwear, money, and abuse. The old charge was alien. The contemporary brand is algorithmic alien. And conflation does the rest.

Meanwhile, what actually changed inside the Church in the last twenty years? Not a lurch into danger, but a remarkably steady picture: mission service and global humanitarian work; lay leadership; a plea for accurate naming; a familiar drumbeat on family, chastity, and service.

So why did the temperature rise now? Several gears meshed at once. From 2012 to 2016, social feeds became the front page; the content that thrived honed villain arcs and moral bite with faster payoff loops.

Streaming fought for differentiation with “based on a true story” limited series that collapsed an offshoot into the whole or an era into the present because simplicity binge‑watches better than footnotes. Investigations—sometimes vital—fed advocacy appeals, which seeded more coverage, which kept the story hot.

And as national institutions lost trust, local communities with strong norms looked suspect by contrast; what used to read as civic virtue now reads as control to audiences trained to equate restraint with repression.

Put bluntly: the villain economy found a familiar mask.

Ministering to Deep and Unmet Needs

That context can help us be less defensive. The people sharing their stories are not attacking Latter-day Saints or their way of life; they are being used by entertainment producers to maximize attention by exploiting their stories to fit into the package that sells today. If attention markets reward heat over light, disciples must choose the Savior’s incentives instead.

In his 1977 talk, “Jesus: The Perfect Leader,” President Spencer W. Kimball taught that “Jesus saw sin as wrong but also was able to see sin as springing from deep and unmet needs on the part of the sinner … We need to be able to look deeply enough into the lives of others to see the basic causes for their failures and shortcomings.”

This counsel to “look deeply into the lives of others” stands in a constructive sort of tension with the Book of Mormon’s depiction of giving no “heed” to mockery and scorn. In the day of the Prophet Joseph Smith, the word heed meant partly “to regard with care.” Then, Latter-day Saints must learn to carefully regard every soul who points the finger of scorn while disregarding the offensiveness of scornful language itself. This can be a difficult line to walk, but it is also the one encouraged by those who seek to follow Jesus Christ.

One practical help here is that our perception machinery is biased by availability cascades (what we keep seeing feels typical) and out-group homogeneity (we infer “that’s how they are” from one vivid case). Knowing that these are human tendencies—not personal attacks—lets us choose slow empathy over quick certainty. And because familiarity often breeds warmth, not contempt, it is good discipleship (and good social science) to actually know the neighbors we’re tempted to reduce to headlines.

To put this another way, we must learn not to be fragile conflict-avoiders who passively stay out of trouble, but Christlike, antifragile peacemakers who actively strive to bring peace to troubled souls. President Russell M. Nelson reiterated his prophetic call for us to become peacemakers until, as it were, his dying breath, highlighting the significance of our efforts while recognizing our ongoing need for improvement. As we recognize both our own parochial concerns with public sentiment against Latter-day Saints and our broader sociopolitical environment of divisiveness and extremism, it is easy to see why peacemakers are needed and will continue to be needed.

Learning from Our “Enemies”

That posture doesn’t just restrain us; it teaches us. The host and individuals who will appear on the screen are children of God. Their stories matter. Our task is to keep clarity and charity together—refusing caricature, refusing contempt, and refusing to let the market’s heat stand in for moral light.

Latter‑day Saints in general are renowned for being enthusiastically kind people, both to outsiders as well as to each other. Yet we, like all faith communities, have our blind spots, and those blind spots tend to enlarge when we are in the majority. And who better to help us learn how to better prevent the lapses that sometimes happen in our policies than those who previously fell victim to them? Christ’s pure love may endure with us.

The landmark book “The Anatomy of Peace” explains that the individuals and groups we consider our most bitter enemies can also teach us about some of our largest moral blind spots. In one of the book’s exercises for “recovering inner clarity and peace,” the authors invite us to ask ourselves a series of introspection questions such as how we, or a group with whom we identify, have made our enemies’ lives more difficult, and how progress toward peace with them might be hindered by our own pride, our feelings of victimization and entitlement, and our desires for validation, status, or belonging. Conducting this kind of searching inventory of our attitudes and behaviors and of those in our faith community is difficult soul‑work, but it yields hearts and congregations that are kinder, more inclusive, and more unified in our quest to build Zion. The alternative is to be damned to continue with our moral blind spots—talking past one another, disregarding or downplaying each other’s needs and pains, and grieving in the gridlock of our seemingly irreconcilable differences.

Because “the pure love of Christ” is so far above and beyond mere human capacity to obtain, we are exhorted to “pray unto the Father with all the energy of heart” to receive this love. We know we are receiving His love as we begin to “look deeply” into the lives of others and see their divine worth, hear the cries of their hearts, and offer them our peaceful presence and care without mixed feelings and motivations. Through faithfully living by the doctrine of Christ and practicing “diligence unto prayer,” Christ’s pure love may endure with us.

When criticism comes: (1) Heed not the mockery—don’t amplify heat. We know why this happens. (2) Regard the person with care—see “a blessed being of light, the spirit child of an infinite God.” (3) Respond in the Savior’s way—facts with fairness, humor with humility, love without capitulation. As we pray “with all the energy of heart,” His pure love will reshape both our moments and our ministries.