You’ve been a devoted member of the local Birdwatchers Association for . . . how long has it been? . . .going on fifteen years now. Although you initially joined almost on a whim, your membership has become important to you: it’s pleasant getting together on a sunny Saturday morning with people you wouldn’t otherwise encounter to go out into nature and appreciate, together, the many-hued marvels of your feathered friends. This is something you’ve come to look forward to.

Then, last week at the association’s annual meeting, something changed. There was the usual business: officers were elected, scheduling discussed, association dues set for the coming year. And then one of the members, Robert, proposed that the Association’s website should add an endorsement of “Black Lives Matter.”

The proposal turned out to be contentious. “We haven’t taken political positions before,” Jennifer objected. “Not that I remember, anyway. Why should we start doing that now?”

“Do you disagree with ‘Black Lives Matter’?” Robert challenged her.

“It doesn’t matter whether I agree or disagree,” Jennifer responded. “My point is that we’re a birdwatching society, not a political organization.”

At that point, you imprudently muttered “That’s right”—quietly, but several people heard you and scowled. And these comments produced a chorus of indignant reactions.

“What’s ‘political’ about being opposed to racism?” Carlos interjected. “It’s just basic human decency.”

“Racism isn’t something any of us can be neutral about,” added Zubaidah. “If we don’t stand up against it, we’re condoning it.”

“Maybe you’ve noticed that we don’t have a lot of African-American birdwatchers in our association,” Max observed to Jennifer (and to you?), with a touch of sarcasm. “There’s a reason for that. Structural injustice. Birdwatching is another reflection of white privilege. We need to correct that.”

If others agreed with Jennifer (and you), they were wise enough not to say so. In the end, the opposition retreated and Robert’s proposal was adopted. You left the meeting disgruntled. You’re not sure whether you want to go to the next activity—to mingle and smile and laugh with Robert, Carlos, Zubaidah, and Max. You’re not sure whether they would want you to come.

A generation or so ago, the proponents of progressive reform often tried to bring more of life into the category of the political

But you’re also afflicted with doubts. Is it true that even a birdwatching society is inevitably “political” and must take a stand on the issues of the day? Are you a bad person– or at least insufficiently committed to social justice— because you want the Association to stick to . . . looking at birds?

Is Zubaidah right that, as someone who wants and pretends to be a decent person, you need to be on record in support of “Black Lives Matter”? As a matter of fact, the basic idea is one you whole-heartedly endorse: Of course the lives of black people matter. And you’ve come to understand that it’s taboo to answer with “All Lives Matter,” although in fact, you believe that all lives do matter—that every human being is a precious child of God. But there seem to be so many associated ideas—about police, and the structure of society, and the need for particular forms of political action, and maybe even the oppressiveness of the traditional family. You’re not even sure what all the associated ideas are, and so you’re not sure what you’ll be taken as affirming if you say that “Black Lives Matter.” So, is it wrong of you to be reticent about making that affirmation?

What is political?

Let’s start with the question: are there ideas or activities or associations (like the Birdwatchers Association) that are—or at least could be and perhaps should be— “not political”? Or is pretty much everything political?

The question is difficult to answer decisively, in part because the term “political” gets used in different ways and for different purposes. A generation or so ago, the proponents of progressive reform often tried to bring more of life into the category of the political. So “the personal is political” was a familiar feminist slogan. Or, sometimes, “the private is political.” In law, the generally left-leaning Critical Legal Studies movement—the “crits”—embraced as a mantra “Law is politics.” (I say “generally left-leaning” because—full disclosure—my academic friends have sometimes described me as a “conservative crit” or a “religious crit.”)

Today, by contrast, the proponents of various reforms or agendas will often deny that an idea is political. Some of us observe this tactic close-up. Your brother David says that he didn’t watch the NBA playoffs this year because the game has gotten “too political,” with political slogans obtrusively displayed on the playing floor and the players’ uniforms. Your sister Angela responds that David is being a bigot. What is controversial after all, or “political,” about equality and social justice?

Or a sister in your congregation wants to post an essay about racism on the Facebook page of your faith community. The essay is thoughtful enough, nothing that could fairly be called radical. But it likely will provoke discussion and disagreement, which is what the author hopes for, she explains; and the essay does contain some assertions and allusions that will likely be offensive to some other sisters. To Sister So-and-So whose husband is a police officer, for example. Told that that specific church Facebook page is not really designed for political debates, the author says, “I don’t see what’s political about what I wrote. Aren’t we—isn’t the Church—against racism?”

Or the director of a major metropolitan choir repeatedly makes pointed public statements supporting same-sex marriage and the LGBT movement; he also makes frequent Facebook posts vehemently condemning racism (accompanied by sweeping accusations), national immigration policy, and the current administration. His programming for the choir’s past season (interrupted by Covid-19) included music, or entire concerts, supporting these causes. When a few members object, he and other choir members respond indignantly that these statements and programs aren’t “political”; they are about justice. Is justice politically controversial? How can decent people object to justice?

So it seems that “political” is a shifty category. It is true that everything in human life—the family, the law, the culture, the media—is a product of, or is affected by, values and institutions and cultural patterns that can be and have been the subject of contested “political” actions and choices (and that work more to the benefit of some people than of others). In that sense, the feminists and the crits were surely right: everything is political. But then again, it is also possible for a person or a community to treat some matters as settled or resolved or not currently within the class of matters that are “up for grabs” and subject to the stormy vicissitudes of “politics.” It is possible to do this, and also desirable—because life becomes unstable and chaotic, and unpleasant if everything is always being argued about and fought over.

The shiftiness of the “political” means that claims of “it’s political” or “it’s not political” can be deployed tactically in support of one or another cause. To call something “political” is to disrupt entrenched understandings and make something a matter of active contestation. Which is what the crits were self-consciously trying to do with law– including with what had been thought of as neutral or nonpolitical subjects like contract law or property law. Conversely, to insist that something is “not political” can be a way of suppressing debate and disagreement—of claiming for your position the force of respectable consensus while marginalizing or silencing your opponents.

Things can get complicated. A choir director who uses the choir to promote, say, an LGBT agenda, but who also deflects objections by asserting that this program is “not political,” is simultaneously deploying the “it’s political” and “it’s not political” classifications. Against traditionalists who think the choir is just for singing beautiful music, the director is acting to disrupt that traditionalist understanding by pulling the choir more into the realm of the political. But in response to those who may question his particular agenda, he is trying to suppress contestation by asserting that the particular ideas or causes he favors are not “political”—i.e., not open to contestation by right-thinking people. (Which is not to say, of course, that the director is self-consciously making use of these tactics: most likely he is simply acting on his own sincere and even taken-for-granted judgments about what should and should not be open to reasonable disagreement.)

If the strategy succeeds, the director and his supporters will have achieved a sort of associational coup. The old settled understanding—the choir as devoted simply to performing beautiful music—will have been replaced by a new settled understanding—the choir as a group that uses music in behalf of particular cultural or political causes.

In the end, therefore, there is no empirically right or wrong, “yes or no” answer to the question: Is this “political”? Rather, the answer to that question will be: It can be political if we want to make it so. The real question is whether we want to classify something as “political,” thus making it a matter of contestation—and likely contention. Or instead as “not political,” thus removing it from the realm of active contestation.

We can treat our birdwatching associations—and our professional sports, and community choirs, and also our Sunday School classes or church Facebook pages—as political. But should we?

Resisting the political, preserving the social order

There is no simple or uniform answer to that question. But there is good reason, I think, to resist politicization—to try to keep as much of life out of the realm of the contested political arena as we can. And I would argue such resistance is especially important at this particular polarized point in our national history.

The reason has to do with the vital importance of what is sometimes described as civic society, or intermediate associations, most of which are typically regarded as “nonpolitical.” The theme has been developed by perceptive observers and thinkers from Alexis de Tocqueville to Ernest Gellner.

In reporting on his visit to America in the 1830s, Tocqueville commented on the role of political associations, but he particularly admired the Americans’ proclivity for forming a whole host of associations “whose objectives have no political significance,” as he put it.

Americans of all ages, conditions, and all dispositions constantly unite together. Not only do they have commercial and industrial associations to which all belong but also a thousand other kinds, religious, moral, serious, futile, very general and very specialized, large and small. Americans group together to hold fetes, found seminaries, build inns, construct churches, distribute books, dispatch missionaries to the antipodes. They establish hospitals, prisons, schools by the same method.

In a similar vein, Ernest Gellner observed that a crucial difference between Western societies and communist or other totalitarian regimes was the presence in the West of a myriad of intermediate, non-governmental associations. Churches. Trade unions. Civic associations and clubs, like the Elk’s Club and the Rotary Club. Birdwatching societies. (I’m not sure whether Gellner specifically mentioned birdwatching societies, but they surely should count in his analysis.)

Tocqueville thought these intermediate associations were important because they were vital in getting community work done that needed to be done—and without direct governmental intervention. Tocqueville and Gellner both emphasized the importance of intermediate associations in promoting civic qualities of cooperation and public-spiritedness while resisting the tendency to move everything into the realm of government—and thus, we might say, into “politics” as well.

These valuable functions are externally-directed, so to speak: Tocqueville and Gellner were appreciating how associations, in carrying out their projects and purposes, confer benefits on the society in which they operate. But today we may appreciate another perhaps even more vital function that is more internally-directed. Quite apart from what (if anything) it accomplishes externally, an association can bring together people of different faiths and tastes and political persuasions—and, potentially, different races and ethnicities—and allow these people to associate around common interests and projects. These groups help people get to know, understand, and even appreciate each other, despite their differences.

It is good for society– and good for us, as human beings—when we have opportunities to notice and cultivate what we have in common

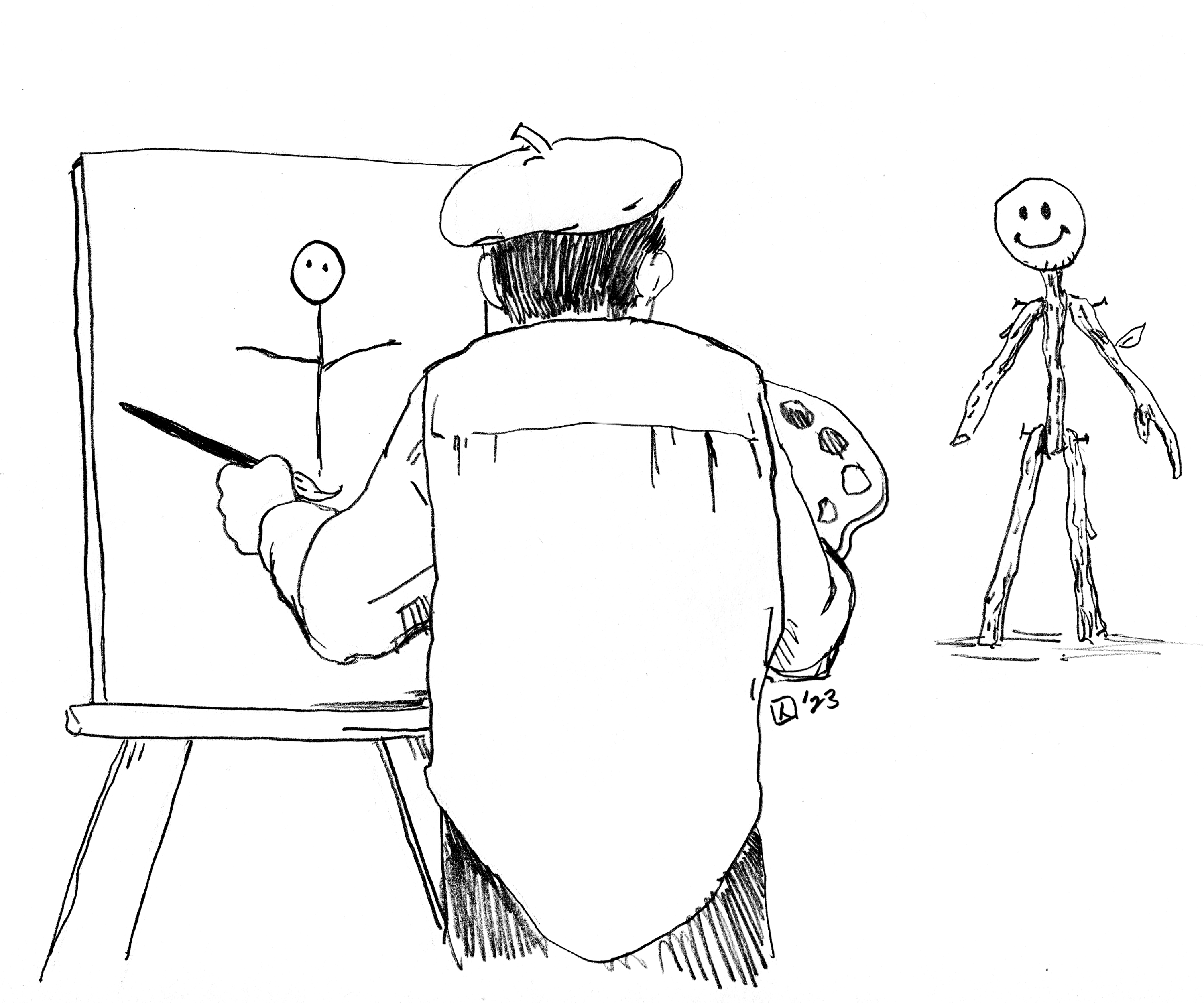

So you may be a Republican (even a Trump enthusiast); Robert may be a Bernie Sanders socialist, but in the birdwatching society you can set aside these differences and join in appreciating the flaming shades of the cardinal or the graceful loops of the red-tailed hawk. You are a devout Catholic, maybe; Maxine is an atheist who thinks your religious views are just plain kooky, but you both are uplifted by joining to sing the magnificent Requiem composed by the agnostic Johannes Brahms.

Or maybe you are a marriage traditionalist. Your neighbor has posted on his front lawn one of those omnibus signs endorsing every currently fashionable reformist cause and idea. You groan at what you perceive as your neighbor’s shamelessly indiscriminate virtue-signaling; he thinks you are hopelessly reactionary in your oppressive views and prejudices. And yet . . . as it happens, . . . both of you are passionate Dodgers fans. As long as you are careful to avoid certain subjects, the two of you can sit down together, crack open a beer—or, if you are Latter-day Saint, a root beer—and bond over the majesty (if the man is on his game) of Clayton Kershaw’s unhittable slider. It turns out, to your surprise, that in most respects he is really a great guy!

As human beings, we all have a lot in common. We also have different and sometimes incompatible qualities— different religious, political, and moral commitments. It is good for society—and good for us, as human beings—when we have opportunities to notice and cultivate what we have in common. The result can be friendship, mutual cooperation, mutual understanding. Even love. “How good and pleasant it is,” sang the Psalmist, “when brothers live together in unity! . . . It is like the dew of Hermon, which falls on the mountains of Zion!”

Conversely, we can hone in on the things that divide us—on our divergent religious and political, and moral views and commitments. The result of that emphasis is likely to be . . . disagreement, conflict, strife. Mutual suspicion. Even hatred. Things that are bad for society, even disastrous, and bad for us as individual human beings.

Keeping our associations on track

Our intermediate associations—our churches, our choirs, our sports leagues, . . . our birdwatching societies—serve a primary role in bringing diverse people together around things we have in common, and thus allowing us to appreciate each other for the varied, rich, remarkable (and, to be sure, deeply flawed) human beings we are. Conversely, as these associations are captured or commandeered to serve particular currently “political” or contentious purposes, they lose their capacity to perform that vital, ennobling function.

Our associations can perform their beneficent purposes if we work to keep them focused on their understood purposes, and refrain from commandeering them for other more extraneous purposes—however valuable we may think those other purposes are.

To be sure, this is not a clear-cut prescription. It calls for judgment and good faith. The purposes of an association are often subject to different interpretations. And the purposes can evolve. In addition, as the preceding discussion should make clear, the prescription does not naively suppose that some associations just are inherently “political” and that other associations are inherently “not political.” We have already seen that every human action and association is in some deep sense political.

Even so, some judgments about an association’s purpose can be defended as sound, and others can be confidently judged as unsound. The core purpose of the birdwatching society is—you know the answer— . . . to watch birds. A proposal to have the society endorse the Democratic candidate for President or the Republican candidate would be to divert the society from its understood purpose—however Lincolnian or Churchillian that candidate might be—or however reprehensibly vulgar his opponent might be. Same for, say, the local Yankees or Red Sox fan club (just as it would be a disruptive diversion for the Republican Party to come out in favor of the Yankees over the Red Sox).

What about a choir? It depends. Someone surely could organize a choir for the purpose of promoting a particular conception of social justice, just as they could organize a choir for the purpose of praising God. The social justice choir would bring together people of potentially diverse religious and cultural views who share a common commitment to singing and also to that vision of justice. Such choirs have played a valuable role in American history.

But if a community choir has long existed to perform good music that is unpolitical—not inherently unpolitical, once again, but unpolitical under community understandings of what is and is not politically contested—a director who seeks to commandeer the choir for a contested cause that he happens to favor is not advancing the choir’s understood purpose (even if his cause is a just one). On the contrary, he is undermining an association that may have served to bring people of diverse political commitments together in a common fellowship.

This can be a powerful temptation for people on the left or on the right—for members of choirs and birdwatching societies and professional associations and churches. After all, your cause is supremely important—isn’t it?—and self-evidently righteous. You are working for “social justice,” or “equality.” Or for “freedom” or “the American way.” What could be more important?

So it is not surprising that more and more associations have succumbed to this temptation. The legal associations I belong to gave in to the temptation long ago—or rather whole-heartedly embraced it. And yet the temptation needs to be resisted. Notwithstanding their lofty professions and pretensions, people who commandeer an association for some political or contested purpose do not occupy the moral high ground. On the contrary, they are undermining the civic order that allows us fallible and flawed and diverse human beings to live together with a measure of decency and peace and even, sometimes, love.

A Plea

Or put it this way: in our intensely and increasingly polarized times, in which Americans on each side of our cultural divides seem bent on demonizing and “canceling” those on the other side, what, if anything, is going to bring us together and allow us to live with each other with civility and respect and even affection? What other than the possibility of mingling together in “non-political” associations around the things—the many, many things, truth be told—that we appreciate in common? But that rapidly-receding possibility will disappear altogether unless we resolve to forego our various righteous causes—not in general, but in particular contexts—and keep our various associations from being taken over by politics.