Elder Jeffrey R. Holland’s recent address at BYU resulted in an outpouring of frustration and anger among some Church members and observers. Among these, many expressed surprise at what they felt was a contrast between the sharpness and directness of Elder Holland’s remarks, versus his expressions of love in that and other previous talks over the years. Some were troubled by his continuation of an oft-used metaphor of “musket fire,” especially in a talk discussing the experience of sexual minorities. But few commentators have chosen to confront the core issue at the heart of his talk: the conflict over identity at BYU and in the broader Church. For those aware of this conflict and its implications for the Church, Elder Holland’s talk was not surprising or novel or shocking; it was only another revealing of an open wound on campus, that in recent years has become intolerable.

Identity fault lines. I don’t believe it is possible to understand the intent and spirit of Elder Holland’s remarks without first understanding in greater depth this core conflict over identity, how post-Christian notions of identity have manifested in recent events, and the ways those notions of identity rival basic Latter-day Saint doctrine.

If Christianity was the field where Western notions of identity formerly were sown, the abandonment of Christianity in the West has turned that field into a fever swamp of identity chaos. Christian notions of identity rooted in the understanding of God as creator and Christ as Savior once offered Western society an understanding of our place in the world, and the moral basis for social movements to address injustices in society. Without a grounding in Christianity, our common understanding of God as heavenly parent and humanity as family have been replaced by atomized rival identities based in politics, nationalism, gender theory, marginalization narratives, sexual orientation, and other aspects of human experience. The use of avatars and anonymous handles in digital environments like gaming and social media has also enabled the rising generation different ways of representing themselves to the world. Identity, like so much else in the West, has become something that can be changed and adapted according to consumer preference. If Christianity was the field where Western notions of identity formerly were sown, the abandonment of Christianity in the West has turned that field into a fever swamp of identity chaos.

I’ve started to accept that fact that I love and feel comfortable with gay and queer-identified men because—wait for it—I am queer myself, and I tout the burgeoning theory of sexual fluidity as my rationale. I suppose I’m finally accepting the notion that there can be straight queers, and it’s more than okay for me to define myself as one.

In response, some have insisted this is yet another example of “identity appropriation.” In response to these concerns about (usually straight and white) people appropriating identities of marginalized communities, “gatekeepers” have arisen to deny people’s claims to marginalized identities. Queer writer Gabrielle Kassel attempts to tackle the problem, noting:

I’ve noticed that many others in the LGBTQ+ community have taken on the word [“queer”], too, along with folks who don’t identify with any of the letters represented in that acronym at all. For instance, some who are polyamorous or who belong to the kink community might identify as queer … I do have to wonder whether this wide use of the word is appropriative [usurping unfairly the status] of the highly marginalized LGBTQ+ community.

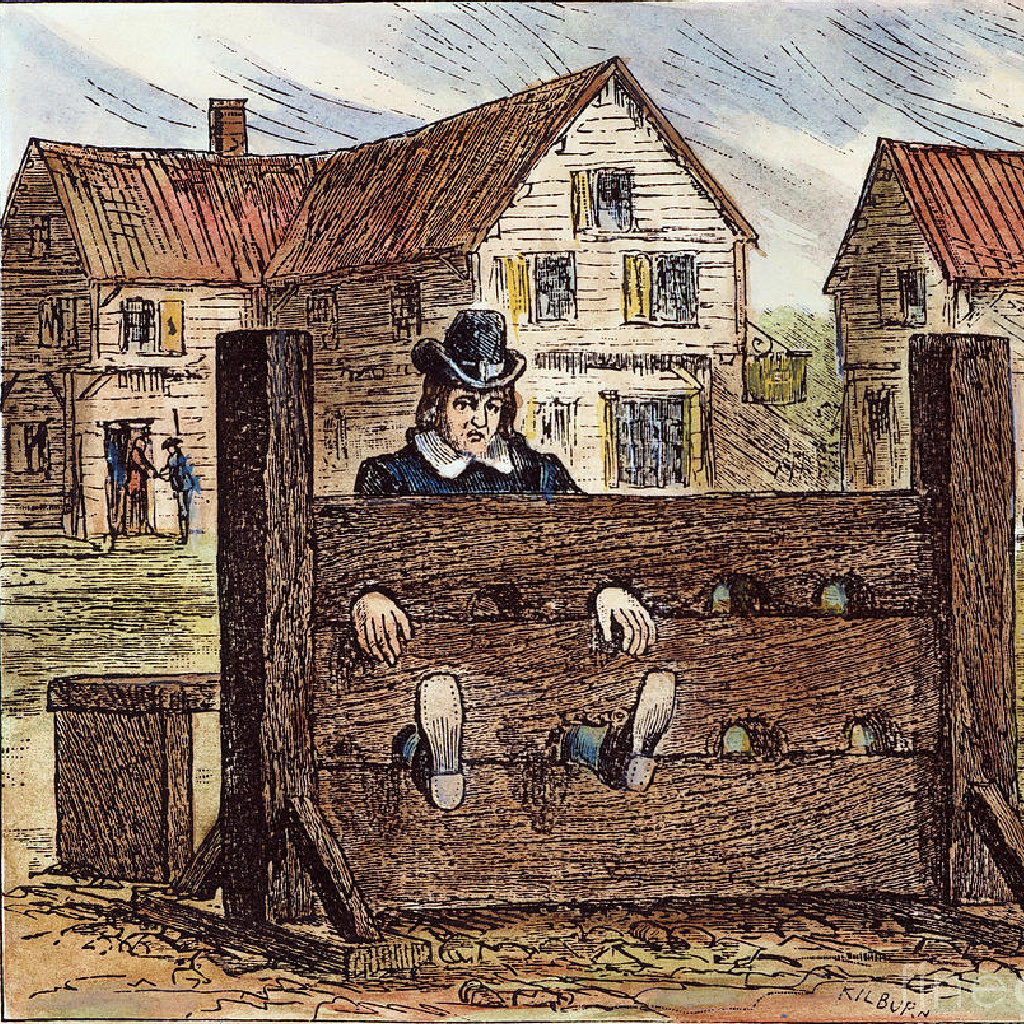

Identity boundaries as hatred and violence. It increasingly seems as if entropy—nature’s tendency toward disorder and randomness—has come to characterize popular thinking surrounding gender, sexuality, and identity. The appeal of entropy lies in the fact that it feels egalitarian and fair. And for people who have developed a love of entropy, any attempt to impose any form of order or boundaries, no matter how loving the motive, will feel like an act of hate.

Kassel herself attempts to offer a clear definitional boundary for queerness: “Plainly put, yes, someone who is straight can indeed be queer, so long as they are not cisgender or not allosexual” (allosexual includes all those who have any degree of sexual desire). She then cites Bahiyyah Maroon’s assertion that “identifying as LGBTQIA+ is a prerequisite for identifying as queer. If you are not those things, it would be more accurate to call yourself a queer ally.” But later in her analysis, Kassel undermines these attempts at more clarity, observing that “The problem with saying who can and who cannot identify as queer in this way is it risks becoming identity gatekeeping.” She then quotes Gabrielle Alexa Noel’s observation that “The result of gatekeeping is that it disconnects a person from their identity. It can be an incredibly disembodied experience.” Queer writer Chelsea Jackson similarly warns that “Having an aspect of your identity questioned is an absurdly invalidating experience …” To prevent the possibility of this unique form of harm, Noel proposes as a solution that “… everyone gets to define queerness for themselves!”

In other words, if these disparate notions of identity are all to believed:

- Identities are defined personally, apart from any objective criteria or shared consensus.

- Any attempt to define an identity in a way that conflicts with another person’s personal definition is “gatekeeping,” which amounts to an act of violence, causing an experience of invalidation and even “disembodiment.”

In recent years, transgender identity has become a locus for all of these questions and contradictions. For example, when a biological male claims to be female because “I feel female,” many feminists respond by questioning what it means to “feel female.” Is it a yearning to wear dresses and makeup? A desire to experience childbirth? What thoughts, feelings, and experiences are essentially female, leading a biological male to make this claim to femaleness? And how does one differentiate between things that are essentially female, versus culturally-informed gender roles and stereotypes that are presumably more peripheral? If identity is something inside of us that we discover, and it is based on our thoughts and feelings and self-perception, and it is immune to criticism or analysis of any kind, then on what grounds do we deny anyone’s claim to any identity?

Whatever you want, however you want. Some commentators have asked what happens if these entropic assumptions about identity are followed to their logical conclusions, and how they can apply to other areas of life. The many headline-grabbing stories of whites appropriating racial minority identities have been the source of public controversy, but those who identify using the new category of transracial (identifying with a race other than one’s ancestry) are merely asking for consistency: if identity is something inside of us that we discover, and it is based on our thoughts and feelings and self-perception, and it is immune to criticism or analysis of any kind, then on what grounds do we deny anyone’s claim to any identity?

This discussion about the parallels between transgender and transracial identity is underway, and as might be expected, it is very heated. Addressing the inconsistent logic employed by critics of transracial identity, David D’amato writes:

That’s where the opponents of transracialism go very wrong: all of the cited [justifications for treating gender transitions differently than race transitioning], are either completely arbitrary, or themselves extremely controversial and unsettled, or simply unable to carry the heavy burden of denying someone something so central to her personal identity.

… The opponents of transracialism can’t decide why they so execrate the idea, can’t agree with one another about what makes it so appalling a suggestion. If they admit the truth that one’s self-perception and self-identity are completely subjective, determined by an infinitely complex jumble of social, cultural, biological, and other factors—some learned, some not, some innate, some not—then they give away the game; they would then have to admit that it is arbitrary, insensitive, and ultimately unfair to deny to the individual membership in her professed race.

D’Amato ultimately concludes with a blanket statement that imposes consistency upon the two camps —asserting, simply, that “A free and open society should defer to an individual’s self-identification, not shame her for embracing her agency and individuality.”

The difficulty that this mindset presents for society is illustrated in recent events: a UK influencer’s possibly fatuous announcement that he identifies as Korean, with surgical procedures underway to bring his body in line with his identity; Vermont Governor Phil Scott’s announcement of availability of COVID vaccines to people who identify (regardless of their actual ancestry or complexion) as Black, Indigenous, or a person of color (BIPOC); and finally, an incident where an individual with male genitalia strolled nude through the women’s changing room of a spa, leading to outraged clients along with subsequent violent protests in support of the biological male. In response, major news outlets suggested the incident was a “transphobic hoax,” until it was revealed that the perpetrator was in fact an individual named Darren Agee Merager, with two prior convictions for indecent exposure. In light of this information, Merager insisted the controversy represented clear transphobic sexual harassment. All of these situations involve conceptualizing identity as something that is individually determined and expressed in ways that a significant percentage of society is not able to honestly affirm.

The psychologized self. In his book The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self, Carl Trueman points out that self is a concept that needs defining, and the wealthy, post-enlightenment West defines self in a particular way that differs from traditional notions of identity that are still widespread in the Majority World. Trueman observes that “The psychologized, expressive individual that is the social norm today is unique, unprecedented, and singularly significant. The emergence of such selves is a matter of central importance in the history of the West as it is both a symptom and a cause of the many social, ethical, and political questions we now face.”

In saying this, Trueman is making the important assertion that in contrast with what we see in popular Western culture, there historically have been other ways of arriving at our conceptualization of identity. The Bible offers many examples to support this. The great outpouring of the converted soul, Psalm 23, offers the statement, “thou anointest my head with oil,” in reference to the common initiation ritual of kings and queens, priests and priestesses— hinting that this profound phrase might well be expressed as you reveal to me my true royal and priestly identity. In order to maintain this contrived identity, one must avoid exposure to anything that will challenge it. The whole world, then, must collude with this identity construct.

By contrast, the popular Western framework of identity that Trueman describes is one that creates identity out of our perceptions, desires, sexual orientation, personality, aesthetics, appetites, and experiences. Trueman gives voice to the fragility of these identities: “That which hinders my outward expression of my inner feelings—that which challenges or attempts to falsify my psychological beliefs about myself and thus to disturb my sense of inner well-being—is by definition harmful and to be rejected.” In other words, in order to maintain this contrived identity, one must avoid exposure to anything that will challenge it. The whole world, then, must collude with this identity construct.

Invoking current events, Trueman continues: “The refusal to bake me a wedding cake, therefore, is … an act causing me psychological harm. There is therefore an outward, social dimension to my psychological well-being that demands others acknowledge my inward, psychological identity.” To secure people’s compliance, people sometimes go so far as to engage in emotional extortion, threatening harm to themselves or others unless some aspect of self-perception is validated by other people.

This insatiable need for other people’s affirmation contrasts sharply with the converted Psalmist, whose divinely-proffered identity leads to an emotional state described in terms of “wanting nothing,” like a “cup that runneth over.” Divine identity does not require validation from others and does not insist the entire world align with one’s views.

Believers in the restored gospel share a conviction that this divinely-proffered identity began to be formed eternities ago in the presence of Heavenly Parents. The implications of this appreciation for our identity today cannot be overstated; for instance, it’s hard to assert that this or that mortal experience is who I am when we contemplate premortality and realize we don’t even know our own names. Our true identity existed long before any of our present experiences, and it is never discovered, only remembered. Since this understanding of eternal identity forms the basis for our inclusion and belonging as a community, the adoption of identities based on specific perceptions or experiences reduces our ability to form meaningful human connections.

Identify and suffer. Buddhism shares with the restored gospel some common insights regarding identity. According to Buddhist psychology, when we say of thoughts, feelings, perceptions, and desires “This is who I am,” we are engaging in identity delusion that leads to ever-increasing suffering. The Buddha originally raised caution about “unenlightened” individuals who regard “feeling as self … perception as self … volitional formations as self … consciousness as self …” From this vantage point, form (matter, or body), feelings, perceptions, thoughts, and consciousness are understood to be categories of human experience that we use to construct false identity, and a delusionary “false self”—subsequently striving in vain to maintain this false self through attachments to career, recognition, financial success, the validation of others, and other illusory experiences of affirmation and control.

The Dalai Lama says of this “dissatisfied mind” and its transitory, unstable happiness:

We want something and work hard to get it, but somehow having it brings more suffering than pleasure in the end. Samsara [the nature of life and death] is such that one is constantly in the situation of being pained by having or else by not having… We think that if we buy something, possess something, or move to another country, our mind will be satisfied; but there is no satisfaction in [this] approach. Unless we develop the wisdom giving freedom from karma and delusion, all happiness is bound to eventually dissolve and be replaced by sufferings.

Buddhism rejects the idea of self as it is defined in our post-modern contexts. Among other things, the practices of Buddhism are embraced as a way to liberate oneself from the various forms of attachment and “grasping” that we employ to sustain a false construct of self, which construct keeps us in a constant cycle of suffering.

Identifying in something deeper than feelings. In a discussion that speaks to current debates over gender identity, YouTube commentator Daisy Chadra shares her experience as a girl who identified as a transgender boy, then underwent transition to alleviate what she calls “dissonance” between her body and her feelings of gender. In a video announcing her detransition, Daisy recalls the initial cycle of transition steps followed by regret, followed by affirmation of others, and then more transition steps: “when one step ended, I would immediately start thinking about the next step … but when it was finished, I was left incomplete.”

Daisy frankly acknowledges the relentless social influences that contributed to her inner confusion:

Part of why this regret [of transition] was so difficult was that I believed—or had been told to believe—that if I came to regret my transition, I would likely kill myself. Or, if I didn’t transition at all, I would likely kill myself. If it had not been for that narrative, I think I would have been able to get through the dysphoria, and develop as my own person.

Ultimately, Daisy’s downward spiral was halted with a turn to God:

I had believed in God before this, but not a personal God, not a God that intentionally makes and guides every single individual; not a God that cares about me…

I wanted to be born again, but not in Christ. I wanted to be in control, not to submit. So I chose to worship my “identity,” masculinity …

I couldn’t deal with the female part of me. I couldn’t deal with myself as I was, as God made me …

There is a part of me that is deeper, that is God-given; and I finally realized that that part of me is female …

One day I just decided I’m going to try taking the Bible seriously, as truth …

So I started praying as I would read scripture. And I would pray with the understanding that the almighty God, the creator of the universe, was listening … and I had some very powerful moments …

There’s really no other way to say this … I felt the presence of God. I wasn’t really looking for it; it just came over me … for the first time I knew what I really believed, and I knew who I was. I was God’s. I belonged to God …

So I found my identity in Christ, and not in gender. And I continue to pray and read scripture with a submissive heart, and I have never felt more alive in my entire life.

Daisy’s story illustrates what should be the objective of all religion: not the mere application of thoughts and feelings to a set of teachings and narratives, but the facilitation of direct encounters with God, who exists apart from our thoughts, feelings, desires, priorities, and experiences. Her story illustrates the power of scriptural witness in preparing us for these encounters, and it is no accident that the period of her greatest confusion over identity was also a time when she held the same diminished view of scripture that has facilitated Western societies’ abandonment of Christian identity.

A proclamation vindicated. In light of this and many other examples, it is clear why Latter-day Saints who affirm the doctrines in the Family Proclamation feel increasingly vindicated by events around us. Presented in a talk that prophetically warned against social forces combining against women, the Family Proclamation was issued well in advance of what we are presently seeing: the unique reality of femaleness obliterated in favor of terms like “birthing people,” and even gender itself imagined into an undefinable oblivion by social forces that are coercing the acceptance of gender and identity entropy in the name of “inclusion.” These forces consuming society collide in dramatic fashion with the plain and precious truths found in the family proclamation and affirmed in the sacred poetry of I Am a Child of God, I Know My Father Lives, and Eliza R. Snow’s prophetically visionary O My Father.

A common criticism of the Family Proclamation is that its notions of identity, gender, sexuality, and family do not account for the variety of human experiences. This is true of the Family Proclamation just as it is true of all divinely inspired prophetic teachings throughout history. The prophetic standard has always been simply to convey God’s intentions and expectations, and prophets have never been tasked with addressing every permutation of human thought, desire, and experience. At the time the Family Proclamation was issued in 1995, most debates over the family were centered on gender roles, such as the definition of preside, and how fathers and mothers should navigate together the demands of childrearing and careers. But the disciplined and focused nature of the proclamation text is far more radical than those initial debates led us to believe, especially in its claims surrounding identity:

All human beings—male and female—are created in the image of God. Each is a beloved spirit son or daughter of heavenly parents, and, as such, each has a divine nature and destiny. Gender is an essential characteristic of individual premortal, mortal, and eternal identity and purpose.

When many dismissed the Family Proclamation as mundane restatements of Church teachings, it was due to an inability to see into the present day, where these basic statements of identity are now the target for aggressive social forces of gender and identity entropy. For instance, those of us debating gender roles in 1995 could not have envisioned the proliferation of identity declarations on digital platforms like TikTok, where among other things we find an individual claiming to be “Aroace and Lesbian with ‘sub-identities;’” an individual claiming to be “LibraMasc,” which is described as “libra-gender with a connection to the male,” and many other individuals who take a combination of current notions of gender and race identity to their inevitable conclusion: a general inability to form meaningful human connections. When we construct a false identity for an institution and then see that false identity invalidated by those who refuse to accommodate our delusion, it can be an emotionally traumatizing experience.

First, when students confide in faculty and staff mentors their sexual orientation or other aspects of their life experiences, how are these faculty and staff likely to respond? Will they respond by characterizing these experiences as identities whose reality calls for unmitigated affirmation and celebration from every other person? Or, will BYU faculty and staff help students to internalize their divine identity and underscore the foundational nature of that identity as distinct from other feelings and life experiences? Do BYU faculty and staff see the social incentives at work in the increasing “discovery” and public announcement of identities, and can they counter these trends by teaching divine identity in ways that facilitate unity and belonging? To what degree do BYU faculty and staff still possess these gospel concepts of identity themselves?

And finally, in light of the fact that Elder Holland’s remarks are a continuation of similarly pointed messages over the years from President Dallin H. Oaks, Elder Neal A. Maxwell, President Hugh B. Brown, and others, how exactly is it surprising or upsetting that this current apostle has continued this ongoing pattern and forcefully reaffirmed BYU’s institutional identity as a temple of learning that will not embrace the identity-based entropy and chaos that have engulfed Western society? As with fragile, false notions of personal identity, when we construct a false identity for an institution and then see that false identity invalidated by those who refuse to accommodate our delusion, it can be an emotionally traumatizing experience. To have our delusions shattered in this way is wholly unnecessary, but to avoid that experience requires us to operate with a clear common understanding of institutional identity to begin with. And also similar to personal identity, BYU’s true institutional identity also exists apart from our thoughts and feelings and inner narratives. The sooner we as a BYU community internalize that reality, the sooner we can calibrate our expectations appropriately and ensure that the next sharp talk from the Board of Trustees will not be surprising. We would do well to make these adjustments now, because in light of past talks from the Board of Trustees, we can be confident that even more pointed, direct affirmations of BYU’s identity are on the horizon.

Ultimately, despite the fact that Elder Holland’s remarks were intended for BYU faculty and staff, the underlying questions of identity in his message are important for all members of the Church to understand. To fixate on a musket metaphor or a valedictory address is unfortunately a superficial reading and response to a talk that is speaking to much deeper issues of identity. When our public discussions reward instant reaction instead of careful attention to context and intentions, it becomes easy to mischaracterize people like Elder Holland and the messages they carry. The decision to read carefully in a spirit of charity, and strive to understand the underlying issues, becomes almost impossible when we erroneously perceive our identity to be under attack. Hopefully we are learning from this episode that there are better ways to respond to God’s ordained servants.